|

|

|

May / June 2006

Informed Consent:

Comprehension is the Key

The challenge hospitals face is that many patients do not understand the fundamental information regarding their treatment plans.

By Neil Baum, MD

Most hospital processes focus on trying to prevent costly medical errors after a patient begins treatment. However, there is a process that starts before patient treatment that can have an even bigger impact on patient safety and quality of care. The informed consent process ideally serves as a way to educate patients about their conditions; the benefits, risks, and potential complications of a procedure; treatment alternatives; and risks associated with not performing the procedure. At present, all of this information is packaged typically as a generic form coupled with a conversation between patient and physician.

The challenge hospitals face is that many patients do not understand the fundamental information regarding their treatment plans. Even though a patient may sign a consent form stating that he or she understands what has been communicated, studies show that even after agreeing to or receiving care, 18% to 45% of patients are unable to recall the major risks associated with their surgeries (Graham, 2003; Saw, et al., 1994; Cassileth, et al., 1980); many cannot answer basic questions about the services or procedures they agreed to receive (Wadey & Frank, 1997; Berlanger, et al., 1980; Lavelle-Jones, et al., 1993); 44% do not know the exact nature of their operation (Byrne, et al., 1988); and most (60%) do not understand or read (60% to 69%) the information contained in the generic hospital informed consent forms (Parker, 2000). Obviously, the lack of fully comprehended informed consent presents significant patient safety and quality of care risks and can also lead to increased medical malpractice risk for hospitals and for physicians.

As forward-thinking hospitals realize this liability and consider ways to address it, emerging technology offers a cost-effective and easily-implemented solution that not only decreases the risk of adverse malpractice judgments, settlements, and legal costs but also improves the quality of care by enhancing the communication between the physician and the patient.

Quality and Safety Organizations

Lead the Push

The 2000 publication of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, captured the attention of the public and policymakers relative to the patient safety risks associated with medical care. In response to these findings, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality commissioned its own report to evaluate various evidence-based, best safety practices. Published in 2001, Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices reviewed 79 patient safety practices and focused special attention on 11 practices deserving of widespread implementation. One of these practices was: "Asking that patients recall and restate what they have been told during the informed consent process." This was an effort to ensure that patients not only read and heard the informed consent, but more importantly, understood the informed consent.

Further, the National Quality Forum (NQF), an organization chartered to develop and implement a national strategy for healthcare quality measurement and reporting, released a report, Safe Practices for Better Healthcare, that endorsed a set of national, voluntary consensus standards for 30 healthcare practices aimed at improving patient safety throughout the healthcare system. This strategy, called Safe Practice 10, states that all healthcare professionals should ask patients to repeat or "teach back" what they have been told by their provider during the informed consent discussion.

In December 2003, the NQF initiated a project to accelerate widespread adoption of Safe Practice 10. That effort resulted in the September 2005 publication of an implementation report, Improving Patient Safety Through Informed Consent for Patients with Limited Health Literacy, and a user's guide, Implementing a National Voluntary Consensus Standard for Informed Consent. The following real-life examples from the user's guide demonstrate the need for Safe Practice 10:

- A Spanish-speaking woman walked out of the hospital just prior to surgery when it was finally communicated clearly to her that tubal ligation was a permanent sterilization technique, not a temporary method of birth control.

- The planned anesthesia for a patient was incompatible with Coumadin, but the patient did not report use of Coumadin until "teach back" was used at a late stage of the pre-operative process, allowing providers to avoid a potentially fatal interaction.

- Four months after starting to use "teach back," one hospital department, which frequently saw 100 patients per day, dropped the surgical cancellation delay rate from 8% to 0.8%, resulting in a savings of $56 per minute for the resources that previously had been wasted by cancelled or delayed surgeries.

Technology Helps Meet

Emerging Guidelines

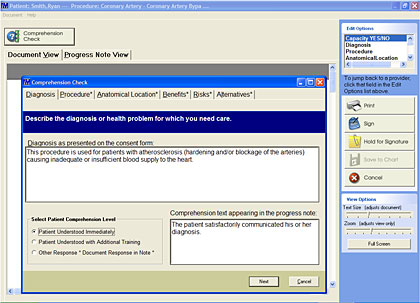

As NQF's efforts to spur adoption of its Safe Practices for Better Healthcare continue to gain ground, hospitals are encouraged to address the inconsistencies and inadequacies of the traditional informed consent process with an eye toward achieving fully comprehended informed consent on a consistent basis. Many hospitals are finding that an automated informed consent application is the best way to meet these and other emerging guidelines (Figure 1).

|

|

|

|

|

|