|

|

|

November / December 2007

Zero Tolerance

Curbing Catheter-Related

Blood Stream Infections

By Chris Abe, RN, BSN, CIC, HEM;

Jeanne Zack, PhD(c), RN, CIC; Stephen R. Lewis, MD;

Tim Vanderveen, PharmD, MS

The focus of a recent webcast reflected the heightened concern among clinicians and the general public regarding all types of healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs). Currently CR-BSIs occur in an estimated 3% to 7% of intensive care patients with central venous catheters (CVCs) (Raad, 1998). Central line-associated bacteremia, primarily seen with CVCs, can increase the intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay by 6 days and hospital stay by 21 days, while adding a cost of $56,000.

Historically it has been acceptable for a hospital's rate of catheter-related blood stream infections (CR-BSIs) to be at or below the Centers for Disease Control's (CDC's) rate of 5.7 per 1,000 catheter days. Today the goal is zero. For the health and safety of both patients and clinicians, infections due to lax vascular access procedures and protocols should be addressed, so that needless complications can be avoided. Multiple organizations, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, The Joint Commission, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, have undertaken improvement initiatives to help clinicians attain the goal of zero tolerance.

Presenters emphasized that adopting a zero tolerance approach to CR-BSIs is an attainable and clinically imperative goal in today's healthcare arena. Soon, healthcare facilities will no longer be reimbursed for HAIs, including CR-BSIs, forcing practitioners to find workable solutions to prevent infections. Back-to-basics hygiene programs and stringent, recurring education are working in hospitals nationwide to significantly reduce and eliminate CR-BSIs.

In the opening presentation, Black pointed out that the widespread implementation of needleless IV systems has reduced the rate of percutaneous injury from IV catheter needles from 1.78/100 occupied hospital beds to almost zero. The use of newer catheters with antimicrobial and antiseptic solutions also reduces the risk of CR-BSIs. However, the use of these devices is only an adjunct to ensuring the proper insertion, use, and care of CVCs. An unintended consequence of needleless system use has been the mistaken impression among even seasoned healthcare professionals that contamination is no longer a serious risk. Black emphasized that proper asepsis is critical to protect the patient from avoidable blood stream infection while also protecting the healthcare worker from injury.

Building the Case for Diligence

A knowledge deficit regarding aseptic technique is a factor in CR-BSIs that can easily be corrected with proper education and consistent reinforcement of best practices, Alexander noted. Nurses' workload is constantly increasing, and having to do more with less has become commonplace. The basics of aseptic technique, especially when IV-related procedures are performed, are often omitted. Inadequate site preparation to maintain sterility during catheter placement, failing to properly disinfect needleless access ports, and lack of basic hand hygiene all contribute to the infection problem.

In the Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice developed by INS, out of 72 standards there are several that relate specifically to best practices for preventing CR-BSIs. Alexander emphasized that the standards should be applied to all practice settings and competency should be validated on a routine basis. Among the standards is:

- The nurse providing infusion therapy shall be proficient in its clinical aspects and shall have validated competency in clinical judgment and practice.

Other standards that should be adhered to include:

- Aseptic technique should be used for changes to all add-on devices such as stopcocks, extension sets, injection and access caps, and needleless systems.

- To prevent the entry of a microorganism into the vascular system, the injection or access port shall be aseptically cleansed immediately prior to use.

- Anytime an injection or access cap is removed, it should be discarded, and a new sterile one should be attached (Infusion Nurses Society, 2006). (A complete listing of the 2006 Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice is available on the INS web site at www.ins1.org.)

The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee of the CDC recommends that hospitals implement comprehensive educational programs to teach proper CVC insertion and maintenance techniques. Those include:

- use of maximal barrier precautions (i.e., surgical mask, sterile gown, sterile gloves, and sterile drapes);

- catheter placement in the subclavian vein rather than an interior jugular or femoral vein;

- changing catheters only when necessary; and

- changing CVC exit-site dressings only when soiled, bloodied, or become non-occlusive (Warren, et. al., 2006).

Smetzer concurred with the assertion that there is less focus on aseptic technique, which appears to be an unexpected outcome associated with the implementation of needleless IV systems. Before the introduction of needleless systems, when a line was hanging between uses, healthcare practitioners typically replaced the needle used to connect the infusion to the IV tubing with a new sterile, capped needle to prevent contamination. Now it appears that many practitioners are not considering the risk of contamination and are not placing a sterile cap on the exposed tubing. While needleless systems have dramatically reduced the risk of needlestick injuries, some have speculated that the lack of a needle or cannula on a syringe or at the end of the tubing may suggest that protection and disinfection is not required.

To reduce CR-BSIs, ISMP recommends heightened awareness of the issue, as well as general practice changes such as covering the exposed end of IV tubing used for intermittent infusions with a new sterile cap, disinfecting the port as prescribed by the specific disinfectant, having written policies and procedures, and ensuring validated competencies. Smetzer noted that there is no "magic bullet" other than going back to the basics and stressing the need to maintain aseptic technique at all times.

Changes in Practice Achieve Notable Results

The challenges to maintaining low CR-BSI rates include staff turnover, low attendance at training sessions, staff complacency, the need for recurring hospital-wide programs to eliminate CR-BSIs, and the simultaneous changes in practice and protocols with the implementation of new products. While these factors can impede efforts to reach a zero CR-BSI rate, an extensive literature review and reports of clinical success illustrate how zero tolerance can work in hospitals around the country.

The success of safety initiatives such as the Keystone ICU Project, which resulted in a decreased mean rate of CR-BSIs from 7.7/1,000 catheter days to 1.4/1,000 catheter days at 16 to 18 months, is evidence that sustained diligence achieves positive results. a 66% decrease in CR-BSIs was maintained over the course of the 18-month study, which covered a total of 375,757 catheter days in ICUs at 103 hospitals (Pronovost, 2006).

The Keystone Project's success was based on a comprehensive, sustained approach that included CR-BSI intervention practices such as hand washing and full-barrier precautions during line insertion, chlorhexidine cleaning of the skin, avoidance of the femoral site, and removal of unnecessary catheters. a unit-based safety culture and daily goal sheets were developed, as well as continued education on infection control practices. Other factors that contributed to the success of the project were the use of central line carts, checklists, and nurses' ability to stop procedures if practitioners did not adhere to best practices (Pronovost, 2006).

Another study of an education-based intervention took place in 13 ICUs at six academic, tertiary-care hospitals for 15 to 18 months beginning in January 2002. The intervention included reviewing and updating hospital and/or unit policies and procedures concerning the insertion, care, and use of non-tunneled CVCs, as well as instruction and self-study modules accompanied by 24-question, identical pre- and post-tests. Believed to be the first multi-center, education-based intervention to prevent CR-BSIs among patients at acute care facilities, the study produced a 21% decrease in the overall incidence of CR-BSIs (Warren, et. al., 2006). Other results of the intervention included:

- approximately 131 CR-BSIs were prevented (Raad, 1998);

- 13 deaths attributable to CR-BSIs were averted;

- 260 to 286 days of hospitalization were avoided (Renaud, 2001); and

- $3.1 to $4.3 million in excess hospital costs were saved (Dimick, 2001; Digiovine, 1999).

Zack was able to achieve notable success through a comprehensive education program to reduce the incidence of central line-associated bacteremias (CLABs) while working at Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH). Zack took that knowledge with her to Missouri Baptist Medical Center (MBMC), where even more impressive reductions were seen in vascular line infections.

At BJH the development of a thorough education module, which included fact sheets, posters, self-study module and testing, enabled staff to substantially reduce CLABs by 66% (to 3.7/1,000 catheter days). Of particular note was the knowledge score of nurses: the pre-test score of 78.3% jumped to 89.9% following implementation of the self-study modules. By instituting these education modules, a cost savings of between $185,000 and $2.8 million was realized (Coopersmith, et al., 2002).

A study at MBMC from July to September 1999 showed that a focused education intervention among nurses and physicians in a non-teaching community hospital resulted in a significant, sustained reduction in the incident of CLABs: in the pre-intervention period 30 cases of catheter-associated BSIs were noted during 6,110 catheter days (4.9 cases/1,000 catheter days) compared with 11 cases during 5,210 catheter days (2.1 cases/1,000 catheter days) in the post-intervention period (Warren, et al., 2003).

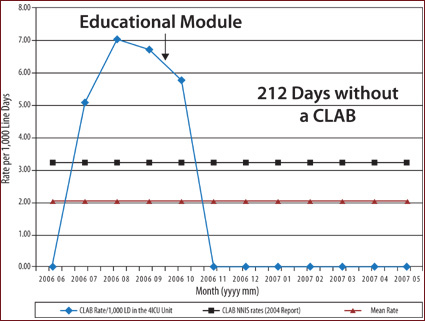

In August 2006, a quality improvement program in two ICUs at MBMC resulted in zero CLABs for a sustained period of time. Following an extensive education program, one unit (6-ICU) had reached 182 days consecutive without a CLAB and another unit (4-ICU), 212 days (Figure 1). These success rates were communicated regularly to staff, which served as motivation for continual diligence with central line insertions and central line care and maintenance.

Continued success is based on administrative, physician and nursing support and patient safety champions; feedback on BSI rates presented to staff on a regular basis; an annual educational module testing; and inserting pictorials in both resident manuals and on procedure carts. Zack emphasized that a culture of zero tolerance for infection prevention is the key to keeping patients safe.

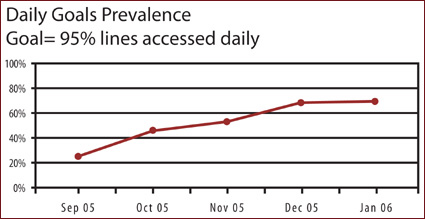

Abe reported on a pilot project 2 years ago at Rady Children's Hospital to reduce CR-BSIs in children by implementing a series of evidence-based practices (bundles). One of the project goals was to have 95% of patients with a CVC have daily documentation of assessment for necessity of retaining the CVC (Figure 2). Removing an unnecessary line would remove an opportunity for infection. In addition, infection rates were to be reduced by 50% (below 2.8/1,000 catheter days); days between infections were to be doubled (more than 20 days), and compliance with the maintenance bundle was to be 100%. Data were to be posted regularly and shared with staff.

As part of this initiative, a 30-second "hub scrub" also was instituted. Prior to connecting to an injection port, nurses must perform a 30-second "hub scrub" using alcohol and friction in a twisting motion, as if juicing an orange. Abe described how nurses developed a variety of ways to determine 30 seconds, such as singing "Happy Birthday" twice.

For those hospitals considering targeting reduced infection goals, Abe noted that plans for change must be communicated early and any changes in practice need to be reviewed by a cross section of staff at all levels with a variety of experiences and backgrounds. Constant feedback to staff on the outcomes has proved to be critical for continued success.

Summary

Throughout the webcast on CR-BSIs, the nationally recognized presenters emphasized that achieving and maintaining zero tolerance requires continuous attention and commitment to ensure adherence to the best evidence-based practices, as well as cultural and procedural changes reinforced by recurring education, reminder systems, assessment of competency, physician and nursing champions, data, and ongoing feedback to staff. Published reports and clinical experience show that zero tolerance for CR-BSIs is possible and imperative.

|

On August 17, 2007, a nationwide webcast, "Best Practices to Reduce Catheter-Related Blood Stream Infections" (CR-BSIs) hosted by the Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence, brought together a distinguished faculty of nationally recognized experts to share their experiences with colleagues as they journey toward "zero tolerance" for central-line infections. The 90-minute, interactive webcast drew practitioners from more than 700 sites throughout the country and Canada. Speakers on the webcast included:

- Chris Abe, RN, BSN, CIC, HEM, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, California;

- Mary Alexander, MA, RN, CRNI, CAE, chief executive officer, Infusion Nurses Society;

- Lisa Black, PhD, RN, assistant professor, Orvis School of Nursing, Reno, Nevada;

- Stephen Lewis, MD, chief medical officer, Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence, San Diego, California;

- Judy Smetzer, RN, BSN, vice president, Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntingdon Valley, Virginia; and

- Jeanne Zack, PhD(c), RN, CIC, manager, Infection Prevention and Control, Missouri Baptist, St. Louis, Missouri.

The entire webcast can be viewed at www.cardinalhealth.com/clinicalcenter. This article summarizes key points from the various presentations.

|

|

Chris Abe is the senior director of Professional and Support Services at Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, California. Abe holds certifications in pediatric nursing, infection control, and healthcare and environmental management. She has over 21 years of pediatric healthcare experience in a variety of roles with extensive experience in program design and management and a distinct skill of incorporating the larger global picture into efficient operational programs.

Jeanne Zack is the manager of Infection Prevention and Control at Missouri Baptist Medical Center in Saint Louis, Missouri, and is certified in infection control. She has held positions as an infection control specialist, a research assistant and adjunct faculty at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and Jewish College of Nursing and Allied Health Services. She speaks nationally about interventions to reduce infections and has published extensively in the literature. Her work in reducing infections using educational interventions has been replicated in Thailand.

Stephen Lewis is chief medical officer for the Clinical Technologies and Services (CTS) business segment of Cardinal Health. He leads the Clinical Standards and Practice area — the Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence — which provides advice, expertise, and oversight around all clinical practices, and establishes the clinical direction for CTS. Lewis is responsible for establishing clinical protocols, aligning clinical strategies with business strategies, and supporting safety and quality efforts at the bedside and point of care. Previously, he was vice president of medical affairs at VHA Southeast. Lewis is board certified in internal medicine as well as quality assurance and utilization review, and is a member of the American College of Physicians and the American College of Physician Executives.

Tim Vanderveen is vice president of Cardinal Health's Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence. He is responsible for ensuring the Center's commitment to education and innovation to reduce variation in clinical practice and to supporting hospitals' patient safety initiatives. From 1972 to 1982, Vanderveen was the director of clinical pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina. Since 1983, he has been in the medical device industry, with IMED, Alaris® Products, and most recently Cardinal Health. He has been instrumental in many of the safety and performance enhancements and safety innovations in drug infusion. Vanderveen has authored numerous patents, is a frequent speaker on medication safety at educational programs, and routinely contributes to the medical, pharmacy, and nursing literature. He may be contacted at Tim.Vanderveen@cardinal.com.

References

Coopersmith, C. M., Rebmann, T I., et al. (2002). Effect of an education program on decreasing catheter-related bloodstream infections in the surgical intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine 30, 59-63.

Digiovine, B., Chenoweth, C., Watts, C., et al. (1999). The attributable mortality and costs of primary nosocomial bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 160, 976-981.

Dimick, J. B., Pelz, R. K., Consunji, R., et al. (2001) Increased resource use associated with catheter-related bloodstream infection in the surgical intensive care unit. Archives of Surgery, 136, 229-234.

Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. (2006). Journal of Infusion Nursing, 29(1S), S15-16.

Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S,, et al. (2006). An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(26), 2725-2732.

Raad, I. (1998). Intravascular-catheter-related infections. Lancet, 351, 893-898.

Rello, J., Ochagavia, A., Sabanes, E., et al. (2000). Evaluation of outcome of intravenous catheter-related infections in critically ill patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 162, 1027-1030.

Renaud, B., Brun-Buisson, C. (2001). Outcomes of primary and catheter-related bacteremia: a cohort and case-control study in critically ill patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 163, 1584-1590.

Warren, D. K., Cosgrove, S. E., et al. (2006, July). a multicenter intervention to prevent catheter-associated bloodstream infections. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology.

|

|

|

|

|

|