|

|

|

May / June 2006

The DUN Factor:

How Communication Complicates the Patient Safety Movement

By Michael S. Woods, MD

The medical profession is legendary for applying linear logic and scientific method to any problem it faces, whether it is a disease or the current center of attention — patient safety. The approach has resulted in great successes, and medicine today has conquered things our medical forefathers would have considered science fiction. But this approach has also resulted in a hammer mentality: every new problem looks like a nail. It is the almost religious belief that everything and anything we encounter in healthcare can be solved if we apply enough brain power and logic, keeping the heat on just a little longer, until the problem is distilled down to its component parts — discrete, definable, predictable pieces.

Unfortunately, the medical profession, in its single-minded quest to define things to the "nth degree," often fails to learn from other professions. Philip Anderson, the 1977 Nobel Prize winner in physics, a stringent science with a legendary propensity for breaking things down into their elemental components, noted:

The ability to reduce everything to simple fundamental laws does not imply the ability to start from those laws and reconstruct the universe. In fact, the more the elementary particle physicists tell us about the nature of the fundamental laws, the less relevance they seem to have to the very real problems of the rest of science, much less society.

As medicine understands more and more about the human body and its ailments and seeks to define every aspect of care in terms of process to enhance safety, it seems we drift further away from humanism and the very real needs of the individuals we treat. Medicine must stop focusing exclusively on the sterile, linear-reductionist perspective and learn how to make sound scientific judgments while remaining sensitive to patients' emotional needs and being perceptive enough to distinguish important nuances in the complex physician-patient relationship.

The patient safety movement is an incredibly important effort yet sits precariously poised at the edge of the same logic-driven chasm as the rest of medicine, obsessed by a nearly exclusive focus on defining processes as the key to enhancing safety. The movement is on the brink of making the same mistakes as the medical malpractice insurance industry, and the medical profession itself, by ignoring incredibly important aspects of the human relationship as related to patient safety and liability. The patient safety movement, in its current state, is in danger of over-promising and under-delivering unless it includes a focus on the relationship between the caregiver and the patient as a core and critical piece of the puzzle.

Enter the DUN Factor. DUN is my mnemonic for "Dynamic, Unpredictable, and Non-linear," and it reflects how life really "is." In brief, life is DUN. The DUN Factor is responsible for the majority of patient safety breaches and accounts for the terrible medical malpractice environment.

Perhaps nowhere in our daily experience is the DUN Factor more evident than in the communication between two (or more) people. Who would argue that conversation between two or more individuals is not dynamic, often unpredictable and non-linear, especially in emotionally charged situations, as is often the case in healthcare. Think about discussions where politics or religion is the topic. Have you ever used a logical argument — reasoned with — an individual who is upset or emotional about something, only to have it backfire? Regardless of the intelligence of the logic you use, and no matter how convincing it may be to a third party observer, it can inflame one who is not in the same place as you emotionally.

Stephen Covey, the personal leadership guru and author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, notes communication is not something that can be applied efficiently. Communication must be effective. He explains that, with people, "slow is fast, and fast is slow." In other words, effective communication, which may require more upfront time between people, ultimately achieves clarity of purpose and enhanced understanding, resulting in fewer misunderstandings. Ineffective communication, often the result of an attempt to communicate efficiently (i.e. quickly), is unclear, can result in partial or poor understanding — if not overt confusion — and can lead to mistakes. Ineffective communication causes delays, as questions are often needed to gain a clear understanding, and can slow down implementation of instructions. It is, therefore, actually inefficient. Ineffective, hurried communication can also make people angry, especially in emotionally charged situations.

Communication failures have been identified as the root cause of the majority of both medical malpractice claims and major patient safety violations, including errors resulting in patient death.

There is near universal agreement among risk managers in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Europe that up to 80% of malpractice claims are attributed to failures in communication and/or a lack of interpersonal skills, usually of the physician. Reams of data support this. Hickson, et al. (2002) concluded that physicians with the highest risk for lawsuits were poor listeners, often failed to return phone calls, and were rude and disrespectful to patients — all communication behaviors. Research conducted by Doctors in Touch found a statistically-significantly higher risk of claims in surgeons who tended to be conflict avoidant and had poorer team leadership skills, both reflecting less effective communication skills. Even the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) has noted, "Physicians are most often sued, not for bad care, but inept communication" (2005).

These same "inept communication practices" cited by JCAHO result in the majority of patient safety issues. In 1996, JCAHO identified communication as one of the top five issues contributing to the generation of medical errors. More recently, a 2003 study by JCAHO documented that communication breakdown was the root cause of more than 60% of 2,034 medical errors, of which 75% resulted in the patient's death (COPIC, 2005). In other words, 915 people died as a result of a communication error.

And who is responsible for effective communication in directing team-based care? Who is the leader of the healthcare team? The physician. While few would debate that physicians are the healthcare team leaders, many question the effectiveness of physicians in the leadership role.

Sources of Risk in Healthcare Delivery and the DUN Factor

For all the analogies made between the airline industry and healthcare, the one comparison that seems trivialized, if not ignored, is that, in general, well maintained machines are always more predictable than living organisms. Short of mechanical failure (which of course can be caused by a human error, e.g., lack of maintenance), aircraft act predictably. If the pilot makes a decision and acts on it, the aircraft responds in the same way, time and time again. This is clearly reflected in the airline industry's remarkable safety record since the advent of crew resource management (CRM).

This type of predictability does not exist in the realm of the living organism, despite medicine's attempt to define such predictability. For any single intervention carried out with perfect efficiency, accuracy, and technical expertise, there can be multiple outcomes, including serious side effects, rampant infection, and even death. Consider the anaphylactic reaction that results in the death of an individual who has just started a medication that, while clearly indicated and supported by evidence-based medicine, was new to him. This same medication is used safely in tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of people daily.

In their article, Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care, Amalberti, Auroy, Berwick, and Barach (2005) describe three risks that combine in healthcare to generate risk: 1) that of the disease itself; 2) that entailed by the medical decision; 3) and that of implementing the selected therapy (pg. 761). They state, "These three risks generally do not move in the same direction. This complexity makes error prevention harder to predict and grasp." The definitions of these three risks highlight the complexity of healthcare risk and patient safety.

Risk in healthcare is much more complicated than even Amalberti, et al., propose. The paradigm suggested is only partly correct, as is any paradigm. Hopefully, what I propose will stimulate someone else to continue to round out and refine the paradigm in the patient safety and medical liability puzzle.

I agree with the three sources of risk Amalberti, et al., note. I would like to add important elements to their model — elements critical to approaching the issues in patient safety and malpractice risk with eyes wide open.

There are at least two other noteworthy sources of risk to be added to this model: 1) the individual patient's physiologic response to treatment and 2) communication. While work is ongoing in how to predict the physiologic response, it is early, and remains in many cases, theoretical. One example is the new tests that define how an individual may metabolize a certain drug on the basis of his or her hepatic enzyme profile. If he or she has hepatic subenzyme 2D6 in the P450 system, the patient receives Drug A. If 2D6 is not present, Drug B is prescribed.

Communication is a different story. As already noted, ineffective communication is widely acknowledged to be at the root of the majority of patient safety issues and medical malpractice claims. Additionally, the further one progresses along the path of the original three sources of risk, the greater the number of "players," or individuals, involved in the delivery of any given intervention or treatment. The greater the number of players, the more communication becomes critical, albeit complex, and the greater the likelihood for communication gaffs between the players that can lead to safety problems and/or unnecessary liability.

Not only is communication important, the effectiveness of an individual caregiver's communication is probably more variable than diagnostic or treatment options in any given situation, at least in terms of the number of factors that can effect outcome.

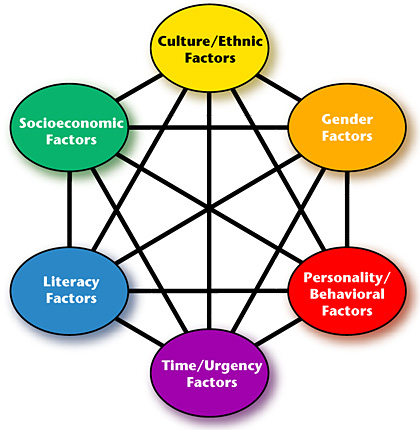

Effective communication requires a speaker to communicate effectively and with clarity to a listener — the person to whom he or she is speaking. The listener must comprehend what is attempting to be communicated. Speaking effectively and accurately and comprehending what is heard is influenced by at least six different communication factors: 1) Cultural/Ethnic Factors; 2) Socioeconomic Factors; 3) Literacy Factors; 4) Gender Factors; 5) Personality/Behavioral Factors; and 6) Time/Urgency Factor (Figure 1). Each of these factors can affect each of the other factors for every party involved in the communication process. This equates to at least 36 variables that can affect the communication outcome between two individuals. Adding a third individual increases the number of variables in the communication equation to 216. A fourth makes it 1,296! In other words, the effectiveness of communication is determined by two or more individuals (and usually, in healthcare, many more than two) and a complex interplay of these six factors within and between each player. The potential for misunderstandings as players are added to the field is staggering. From this perspective, it doesn't seem quite as puzzling why communication plays such a major role in patient safety and malpractice

|

|

|

|

Side Story:

The Six Factors of Communication Risk

|

|