|

|

|

January / February 2008

Getting Connected for Patient Safety

How Medical Device "Plug-and-Play" Interoperability Can Make a Difference

APSF also recognizes that as in all technologies for patient safety, interoperability poses safety and medicolegal challenges as well. Development of standards and production of interoperable equipment protocols should strike the proper balance to achieve maximum patient safety and outcome benefit (Weinger, 2007).

Medical Device "Plug-and-Play" Interoperability Program

The Medical Device "Plug-and-Play" (MD PnP) Interoperability Program was established in 2004 to lead the adoption of open standards and technology for medical device interoperability to support clinical innovation. The term "PnP" was adopted because the required technology infrastructure has many elements in common with the plug-and-play approach used in other computer-based systems. The program is affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), CIMIT (Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology), and Partners HealthCare Information Systems, with additional support from TATRC (U.S. Army Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center). Having evolved from the OR of the Future program at MGH, the MD PnP program remains clinically grounded. The program has been convening diverse stakeholder groups (clinicians, biomedical and clinical engineers, healthcare delivery systems, regulatory agencies, medical device vendors, standards development experts) to learn from past efforts to develop medical device interoperability solutions, to harmonize with current synergistic programs, and to elicit clinical scenarios for "improving healthcare through interoperability." Since the program's inception, more than 600 clinical and engineering experts, and representatives of more than 85 institutions that share a vision of medical device interoperability have participated in ongoing convening activities.

To date, the MD PnP program has convened four plenary meetings to bring stakeholders together for information exchange and discussion of issues related to achieving medical device interoperability. The FDA hosted the second meeting so that regulatory issues could be more thoroughly explored with increased FDA participation.

The most recent plenary meeting was the Joint HCMDSS1 / MD PnP Workshop held in June 2007, which added academic embedded systems experts to interact with stakeholders, attracting 145 attendees. This workshop brought together two highly synergistic research communities (MD PnP and HCMDSS), included a panel of federal agencies (NIST, NSF, NIH, TATRC, FDA), and had as the opening keynote speaker Dr. Robert Kolodner, the National Coordinator for Health IT, generating a more solid connection with the national health IT agenda.

These plenary meetings have been sponsored jointly by TATRC and CIMIT and by TATRC and NSF through conference grants, and by the FDA. Smaller working group meetings have been held to develop program strategy, to work on clinical requirements methodology, to develop interoperability use-case demonstrations, and to work on standards. Our web site (http://www.mdpnp.org/) has provided online discussion forums and information about the program, including streaming video of the talks from the May 2004, June 2005, and June 2007 plenary meetings.

The concept of medical device interoperability is not new. In fact, there have been several earlier efforts to move in that direction, and we have summarized this history in previous publications (Goldman, et al., 2005; Schrenker, 2006). However, none of these prior efforts has met with broad success. Through our conferences and working group meetings, the MD PnP program has identified several causes for historical failures to achieve widespread adoption of interoperability, including the absence of industry-adopted interoperability standards for data communication and device control, and lack of an appropriate "plug-and-play" system architecture (due to emphasis on proprietary solutions). In addition, there have been regulatory concerns and liability concerns that have to be addressed, the few available use cases have been poorly articulated, and the business case for interoperability often conflicts with single-source and end-to-end solutions. These barriers underscore the need for an integrated clinical environment "ecosystem" that would include system functions such as data logging, data security, device authorization, and connectivity to the hospital information system. These functions would contribute to a complete systems solution that could meet clinical, technical, regulatory, and legal requirements.

CIMIT PnP Lab

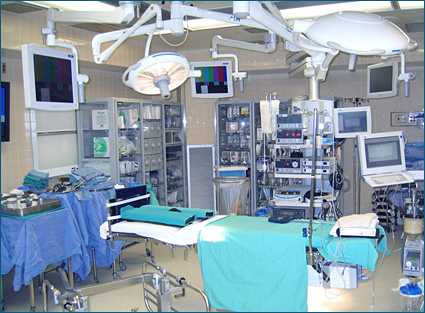

The CIMIT MD PnP Lab opened in May 2006 to provide a vendor-neutral "sandbox" to evaluate the ability of candidate interoperability solutions to solve clinical problems, to model clinical use cases (in a simulation environment), to develop and test related network safety and security systems, and to support interoperability and standards conformance testing. This 500-square-foot facility is outfitted with a high-speed virtual medical network provided by Cisco Systems and installed by Partners HealthCare Information Systems, with access to a patient database of mock EHRs that can be used for testing. In the Lab, we are working with collaborators on the development of demonstrations of interoperability-based patient safety improvements, e.g. improving the safety and quality of portable x-rays and of patient-controlled analgesia systems that are used for pain management.

We have developed and demonstrated scientific exhibits showing how interoperability could improve patient safety in common use cases, showing these at the 2006 and 2007 annual meetings of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), at HIMSS07 (the Health IT and Management Systems Society), and at the 2006 and 2007 CIMIT Innovation Congresses. These exhibits include a demonstration of how medical device interoperability could enable automatic synchronization of x-ray exposure with ventilation, so that there is no need to turn off the ventilator to obtain the x-ray, and a demonstration of how continuous monitoring of a patient's SpO2 and respiratory rate could detect the onset of respiratory depression, and automatically stop the PCA infusion pump, lock out any further doses, and activate the nurse call system. We are currently working on a further variation of the PCA use case demonstration for a scientific exhibit at HIMSS08.

The kinds of resources we are developing in the MD PnP Lab will make it a unique and useful resource for others. A long-term goal of the program is to have the Lab evolve to serve as a national resource for medical device interoperability work.

The MD PnP program has built a multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional team to develop and implement a strategy to address the historical barriers and develop the building blocks or "legos" for interoperability through collaborative projects. Our geographically dispersed team of collaborators includes participants from Kaiser Permanente, the FDA, the University of Pennsylvania, Dräger Medical Systems, Draper Laboratory, LiveData Inc., Mitre, DocBox Inc., the University of New Hampshire, IXXAT, NIST, NSF, and Geisinger Health System, as well as the Partners HealthCare System community (Massachusetts General Hospital Anesthesia, Biomedical Engineering at MGH and Brigham & Women's Hospital, and PHS Information Systems). One of our projects has examined the MD PnP program as a social network, which has evolved over the past 3.5 years from a simple network of 85 people connected primarily to the program leadership, to a larger, complex "smart" network of over 600 people with many connections to each other and who are constantly forming new clusters as they collaborate and bring new people in.

Extending the use of this kind of contract language is a current focus of the MD PnP program. Partners HealthCare is currently considering the use of such language, and other healthcare delivery organizations are increasingly expressing interest.

Defining a safe, "least-burdensome" regulatory pathway for patient-centric networked medical devices, in partnership with the U.S. FDA. An early assumption of this program has been that the goal of medical device interoperability standardization can only be achieved by working closely with the FDA and other regulatory agencies, and this has been our approach to date. The mutual objectives of the FDA and the MD PnP program are to assure patient safety and to identify a regulatory pathway that will support the MD PnP concept, i.e. that will not require re-validation or re-clearance of the entire system as each new independently validated device is added to the MD PnP network.

What is needed for success? Published consensus standards are only one of the ingredients required to achieve interoperability solutions. Other ingredients include the availability of reference implementations of standards such as IEEE 11073 and ICE, interoperability and conformance testing tools, a vendor-neutral testing and evaluation environment (as outlined above), and a safe regulatory pathway. Also, we need a staged implementation plan that recognizes the need to accommodate legacy systems, in order to support widespread adoption of standards-based medical device interoperability.

Today we are seeing a convergence of many factors that are key to success — improved technology, more open-sourcing, technically savvy clinicians, and a willingness on the part of regulatory authorities to consider new validation paradigms. We believe it is now clear that in order for medical device interoperability to become a reality, the following ingredients are required:

- Clinically meaningful, market viable, use cases.

- Open interoperability standards to enable these use cases.

- Reference implementations of the standards and related system architecture.

- Standards profiles or guidelines to describe how to use the standards to achieve interoperability.

- Business conditions that support interoperability.

- Availability of enabling technology.

- Interoperability compliance testing (formal and/or informal).

- Promotion (marketing, education, conferences, evangelists).

1High Confidence Medical Devices, Software, and Systems

Susan Whitehead is the program manager of the Medical Device Plug-and-Play (MD PnP) Interoperability program at CIMIT (Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology), a consortium based at Partners HealthCare in Boston. She coordinates collaborations, communications, and projects for the multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional MD PnP program, which includes a growing network of more than 600 individuals and 85 institutions.

A graduate of Rice University, Ms. Whitehead has worked with computer applications in healthcare settings during most of her career, primarily for Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc. (BBN) in Cambridge, MA. At BBN she managed a major project (CLINFO) that provided NIH-sponsored General Clinical Research Centers with a time-oriented clinical database designed for research, and coordinated other projects ranging from information commerce in a multi-practice clinic to evaluation of the NIH Division of Research Resources by a multidisciplinary panel of experts. She also managed a Technical Support group for BBN Software Systems, and led and trained TQM quality improvement teams at BBN and at PictureTel Inc. Prior to joining CIMIT, Whitehead managed research operations for the Digital/Compaq/Hewlett Packard East Coast research lab. She recently moved from industry into the healthcare sector in order to pursue her interest in applying technology to healthcare information. Whitehead may be contacted at swhitehead@partners.org.

Julian Goldman is director of the program on Interoperability at CIMIT (Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology), a practicing anesthesiologist in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) "OR of the Future," and a physician advisor to Partners HealthCare Biomedical Engineering at MGH. He is the director of the Medical Device "Plug-and-Play" (MD PnP) Interoperability Program, which he founded in 2004 to lead the adoption of open standards and technology for networking medical devices to support high-acuity clinical solutions for improving patient safety and healthcare efficiency.

Goldman received his MD from SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York, and performed anesthesiology residency and research fellowship training at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. He departed the University of Colorado as a tenured associate professor to work as vice president of medical affairs of a medical monitoring company, and joined Harvard Medical School and the Departments of Anesthesia & Critical Care and Biomedical Engineering at MGH in 2002.

Goldman recently served as an officer in the FDA Medical Device Fellowship Program, chairs the Use Case Working Group of the Continua Health Alliance, leads several ASTM, ISO, and IEC medical device standardization activities, and is a founding member and immediate past-president of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia. He may be contacted at www.jgoldman.info.

References

Goldman, J. M. (2005). Getting connected to save lives. Biomedical Instrumentation and Technology, 39(3), 174.

Goldman, J. M. (2006, May). Medical device connectivity for improving safety and efficiency. American Society of Anesthesiologists Newsletter, 70(5).

Goldman, J. M., Schrenker, R. A., Jackson, J. L. & Whitehead, S. F. (2005). Plug-and-play in the operating room of the future. Biomedical Instrumentation and Technology, 39(3), 194-199.

National Academy of Engineering & Institute of Medicine. (2005). Building a better delivery system: A new engineering/health care partnership. P. P. Reid, W. D. Compton, J. H. Grossman, & G. Fanjiang (Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academies Press, Recommendation 4-3.

Schrenker, R. A. (2006, April). Software engineering for future healthcare and clinical systems. IEEE Computer, 39(4).

Weinger, M. B. (2007, Winter). Dangers of postoperative opioids: APSF workshop and white paper address prevention of postoperative respiratory complications. APSF Newsletter.

|

|

|

|

|

|