High Reliability Healthcare: Applying CRM to High-Performing Teams, Part 4

In this series, Steve Kreiser describes a model for applying aviation’s crew resource management to healthcare. This model incorporates different elements inherent in most CRM programs but has an additional benefit of including simple error prevention tools and techniques that help reduce human error. These seven tools, essentially a “people bundle” to make humans more reliable, can help individuals experience fewer errors while encouraging teams to catch and trap those errors that do still occur in complex systems. The series will continue on Tues. and Thurs. through Jan. 19.

Element #3 – Communication

The Joint Commission believes the majority of all events of harm in healthcare are due to breakdowns in communication. This is a fairly broad statement that fails to answer the “whys” of the communication failures. There are multiple barriers to good communications, including wrong assumptions or preconceived notions, hesitancy to speak up due to rank structure or authority gradient, task or information overload (and under-load or boredom), noise and distractions, jargon, and social/cultural/interpersonal problems.

There are a number of error prevention tools that are designed to overcome these barriers while reducing the opportunities for communication failures. Generally, these tools and techniques revolve around a commitment to a frequency and formality in the exchange of information between individuals (handoff point-to-point communications).

In the case of information transfer between individuals (handoff communications), the use of SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) has become a widely accepted best practice for handing off information from one care provider to another. As a content formatting tool it is an excellent device for clearly and concisely transferring information or requesting action from a person with decision-making authority. However, many people do not use it effectively because they fail to preface their communications with each word in the SBAR acronym and therefore fail to recognize the great benefits it offers in structured communications.

As a receiver of information, it is much easier for the human brain to process incoming information if it is packaged in separate “bins.” Therefore, an effective use of the SBAR tool would actually say the word “situation” followed by the headline to get the receiver’s attention, then the word “background” with some amplifying information on the patient condition, followed by the word “assessment”, which forces the sender to exercise some critical thinking skills to assess what they think is going on from being close to the point of care, finishing up with “recommendation,” which really tells the receiver what is needed – the bottom line. If the sender is uncomfortable making a recommendation across a professional gradient, then they should couch their recommendation in the form of a “request.”

The use of repeat-backs and read-backs coupled with one or two “clarifying questions” are essential for ensuring information has been received and understood. While read-backs are a Joint Commission requirement for verbal or telephone orders and critical test results, where the information is written down and then read back to confirm it has been correctly entered into the log or record, the use of repeat-backs are more global in scope. In a repeat-back, the sender transmits the information verbally using the receiver’s name (to get their attention), the receiver repeats it back to acknowledge receipt, and then the sender confirms accuracy with the third leg – “That’s correct” – to close the loop and ensure everyone is on the same page. A commitment to frequent and formal communications emphasizes the use of a neutral confirming statement such as “That’s correct,” which takes away any confusion that can occur with the use of “That’s right” with regard to cases involving laterality.

There are two other important techniques that can make verbal communications more reliable. The first is numeric clarifications. This is where the sender says the number and then the digits to avoid confusion with the sound-alike numbers – such as 15 and 50. For example, if a nurse is given a verbal order to give a patient 15 mg of morphine, in his or her mind they may wonder, Was that 15 or 50?” A best practice is to commit to saying “15 mg – that’s one-five,” which distinguishes it from “50 mg – that’s five-zero.” Clear and concise, and with the use of the separating word “that’s” to avoid any confusion between the number and the digits.

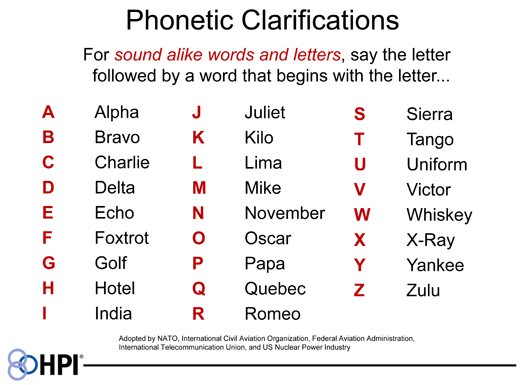

The second verbal communication technique is phonetic clarifications. Oftentimes patient names, medication names, or procedure names can become confused. A best practice is to spell out the word, especially over the telephone. Since there are a lot of sound-alike letters in the alphabet – the B sounds like the C, which rhymes with the D – a best practice is to spell it with the letter in addition to saying a word that starts with the letter. Figure 1 shows a standardized phonetic alphabet in use by the U.S. military in addition to other NATO countries that speak English, civilian radio operators, commercial aviation, and nuclear power. However, other alphabets can and often are used to distinguish sound- alike words and letters.

Figure 1.

High Reliability Tip #3 – All team members should use SBAR for handoff communications, 3-way repeat backs to confirm information transfer and numeric/phonetic clarification to reduce misunderstandings.

Watch for the next post in this series, Element #4 – Assertiveness, on Tues., Jan. 10.