Visual Learning Tools Overcome Health Illiteracy

July / August 2006

Visual Learning Tools Overcome Health Illiteracy

![]()

In today’s “information age,” people are constantly inundated with comprehensive, up-to-the-minute health information. Newspapers and periodicals feature articles and bulletins about the latest medical breakthroughs and health hazards. Popular television shows focus on dramatic cases and miracle cures. And the Internet brings an avalanche of material — some accurate, some misleading — right into our offices and living rooms, day and night.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

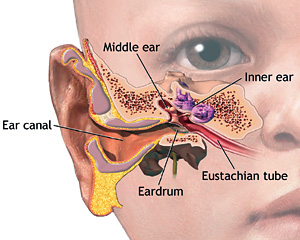

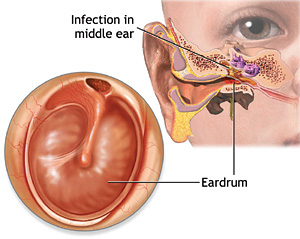

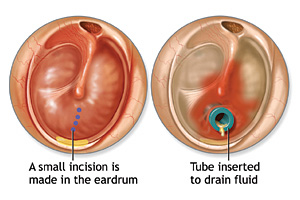

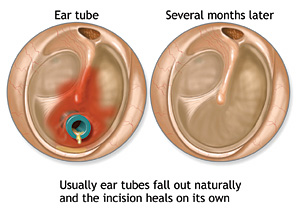

| Figure 1. Ear infection illustrations Images courtesy of A.D.A.M. |

Unfortunately, this information overload can lead us to believe that the patient population is highly educated and has a deep understanding of health matters. Nothing could be further from the truth, as health literacy in the United States is shockingly low. In fact, according to The National Adult Literacy Survey (Jenkins & Baldi, 1992), about 90 million adults (nearly half of the American population) have difficulty understanding and using health information.

The consequences of this statistic are far-reaching. At the individual level, patients often don’t comprehend the diseases or conditions that affect them, and therefore may not follow care plans or take medications appropriately. At the provider level, physicians and other clinical staff can’t be confident that patients understand or will comply with their treatment regimens. And at the global level, billions of healthcare dollars are wasted each year because patients are unable to comply with disease management and health maintenance recommendations (National Academy on an Aging Society, 1999).

Challenges of Low Health Literacy

Low health literacy first made headlines about 15 years ago and, since then, organizations such as the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the American Medical Association (AMA), the National Adult Literacy Survey, and others have thoroughly researched the issue and delivered significant findings.

When looking at literacy in general, for instance, the National Adult Literacy Survey discovered that about 20% of Americans read at a fifth-grade level or lower (Jenkins & Baldi, 1992). On average, Americans read at only an eighth-grade level. Further, health literacy is not only defined as a patient’s ability to read, but also his or her capacity to understand and act on health information.

The problems associated with low health literacy affect all ages, races, and socio-economic backgrounds. Because they comprise the largest segment of the population, the majority of individuals who suffer from health illiteracy are whites born in America. However, disproportionate numbers of ethnic minority groups are similarly affected. The National Adult Literacy Survey showed that those most vulnerable to and affected the most by low health literacy are older individuals, recent immigrants, and individuals of lower socio-economic status. Sadly, these are the segments of the population that are also at greatest risk for chronic conditions, so their inability to comprehend health information has a significant impact on their well-being and quality of life (Jenkins & Baldi, 1992).

In addition, even individuals who demonstrate functional literacy in other areas of their lives may have low health literacy. These individuals may be unfamiliar with specialized medical terminology and clinical jargon, confused by medical concepts, lack understanding about anatomical systems, or fail to comprehend the critical nature of each component of their care plan.

Literacy issues such as these add up to less-than-effective care and wasted medical resources. The National Academy on an Aging Society estimates that, at a minimum, healthcare illiteracy in the United States accounts for more than $50 billion in unnecessary costs each year. Top-end estimates have risen to about $73 billion (National Academy on an Aging Society, 1999).

Barriers to Communication

A number of barriers can add to the challenge of low health literacy.

- First, health information is typically presented at a higher level than general information. In fact, studies have shown that most healthcare materials are written at a tenth-grade level (Doak, C.C., Doak, L.G., & Root, J.H.,1996), which is significantly higher than the average American reading level (eighth grade).

- Second, many illiterate Americans are adept at masking their inability to read and comprehend. They may be highly articulate and have developed coping mechanisms that allow them to function in their personal and professional lives. And, because illiteracy is stigmatized, they go to great lengths to hide their difficulties with reading.

- Third, in today’s fast-paced care environment, physicians often do not have the time to try to determine their patients’ health literacy levels. As a result, most physicians present the required information, give the patient a chance to respond, and then move on to the next exam room.

- Fourth, detailed information is often presented to patients during stressful times when they may not be focused on comprehending it. Before they have the chance to come to terms with a serious diagnosis, for example, they are asked to focus on treatment plans, medications, and follow-up activities.

With these barriers in mind, healthcare organizations can take a number of steps to enhance patients’ understanding of health information. These steps include replacing complicated medical words with plain language and writing information at an appropriate reading level. In addition, more and more organizations are turning toward resources that support visual learning, including diagrams, illustrations, videos, and animations that deliver important information in formats most patients can comprehend.

Visual Learning Support

Visuals have proven to be a valuable asset in building patient-physician communications, enhancing patient education, and improving the informed consent process because patients are better able to grasp the implications of their condition, prognosis, and treatment options. Visuals can increase patient satisfaction and treatment compliance, while helping to reduce the amount of time a physician needs to spend explaining diseases and treatments.

Effective visual tools can range from options as simple as a diagram of the bones in the lower leg that shows various types of bone fractures to a video of the vascular system that demonstrates how balloon angioplasty will treat arteriosclerosis and improve blood flow.

That’s not to say physicians have ignored visual aids in the past. Physicians have long relied on visual aids — such as posters, charts, and plastic models — in their counseling sessions with patients, but these materials couldn’t be sent home with the patient for later perusal.

Tools and Technology

Increasingly, however, health information specialists and software developers have created visual learning tools and technology specifically to address health literacy concerns. This latest generation of support information is designed for the non- or low-level reader. The illustrations are simple, yet complete, and can visually explain a disease or treatment for a patient’s specific situation.

When patient education is delivered through a computer-based system, there is an additional opportunity for delivering interactive and engaging patient education tools such as animations, videos, and full-color illustrations.

Let’s say, for example, that a physician is treating an elderly patient who is recovering from surgery and is at risk for a pulmonary embolism. Because the physician is worried that small blood clots may develop and cause a stroke or heart attack, he decides to place a small filter in the vena cava to capture any dangerous rogue material. He discusses this procedure with the patient, who is confused about this intravascular procedure. Using a computer screen, the physician brings up a video of the circulatory system. With a few simple keystrokes, he demonstrates what might happen if a small blood clot enters the circulatory system. He then shows the patient how he can take x-ray images of the affected blood vessels and, using a catheter, place a tiny filter to block any blood clots from entering important organ systems.

In another case, a young mother has brought her 18-month-old son into the physician’s office multiple times because of ear infections. The physician has determined that the boy should have tubes placed in his ears to ensure that his language skills develop appropriately. The mother has little understanding about otitis media and is very worried about the upcoming surgical procedure.

Using a series of simple illustrations printed from her computer, the physician shows the mother a picture of the ear’s anatomy and a picture showing an ear infection. She uses these two illustrations to point out the effects that the infections have on the child — not only that they prompt pain and fever, but also that they interfere with his hearing, which is vital to the development of speech. The doctor then prints a third picture to demonstrate where the tubes will be inserted, how they will alleviate the problem, and a fourth picture to explain what the mother must do to care for the tubes. Not only do these four illustrations provide the mother with understandable information and assuage her concerns, she is able to take the printed pages home with the physician’s notes to show the child’s father and other worried relatives.

Visual tools like these overcome virtually any literacy problems a patient may display. Not only do they make complex topics easy to understand when first explained, they also help patients retain the information.

A Range of Resources

While using EHRs to deliver educational objectives may be a long-term objective for many healthcare organizations, Web sites and patient portals can provide an effective short-term solution to providing visual health information to a patient population.

Regardless of their literacy levels, many patients are highly motivated to learn as much as they can about their conditions and the services offered by their healthcare providers. Even though seeking information on healthcare Web sites and visiting a doctor are relatively distinct and separate experiences for a patient today, recent technology advances are helping to integrate the clinical encounter with the health information available online. For example, physicians might refer a patient to a Web site that will help prepare the patient for a scheduled surgery or test.

To achieve this goal, physicians can use a wide range of tools available to them, including:

- simple anatomical “guides” to help patients understand various systems within their bodies;

- illustrated, electronic encyclopedia-type databases so physicians and clinical staff can pick and choose material their patients need to see;

- in-depth reports that provide easy-to-follow information about specific diseases and conditions;

- care guides that outline how chronic diseases are diagnosed, what symptoms are cause for alarm, which treatment options are most effective and how patients can manage their disease;

- illustrations that help patients see and comprehend what will happen during specific tests and procedures; and

- videos and animations that explain the progression of disease and the steps inherent in common procedures.

The best of these tools are accompanied by basic descriptions and overviews that have been written in simple, everyday terms. Physicians can mix and match the educational materials — both text and illustrations — to ensure the patients receive comprehensive information in various formats to increase the likelihood that they fully comprehend their condition.

Eventually, as patients begin to have online access to their electronic health records, the doctor could even “prescribe” visual health information for the patient to review, which would be waiting when the patient logged on. This would not only provide a documented record that information was recommended to the patient, but would also capture data regarding which information was actually viewed by the patient.

The result is a winning scenario. Physicians can rest assured they are effectively providing information. Patients gain greater understanding of their health status and are much more likely to comply with their care plan, from taking the proper dose of medication to modifying dietary or other lifestyle habits.

Meredith Nienkamp is vice president of production at A.D.A.M., a leading provider of consumer health information products, and a co-author of the A.D.A.M. Family Health Guide, First Edition. With more than 14 years experience in consumer and academic education, she has been a judge at professional salons, speaker for collegiate leadership programs, and a member of the Association of Medical Illustrators. She holds a masters of science degree in medical illustration from the Medical College of Georgia. Nienkamp may be contacted at mnienkamp@adamcorp.com.

References

Doak, C. C., Doak, L. G., & Root, J. H. (1996). The literacy problem. In Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co.

Jenkins, L., & Baldi, S. (1992). The national adult literacy survey. Washington, DC: Department of Education

National Academy on an Aging Society. (1999). Fact sheet: Low health literacy skills increase annual health care expenditures by $73 billion. Washington, DC.