The Critical Importance of Good Data to Improving Quality

July / August 2012

![]()

American College of Surgeons

The Critical Importance of Good Data to Improving Quality

The ability to fairly, accurately, and meaningfully measure—and remeasure—the quality of healthcare is a challenging prerequisite to assessing and improving it.

Simply put, you cannot demonstrably improve what you cannot measure; and to measure, you need good data—data that are fair, accurate, and robust. Good data allow you not only to assess the quality of care, but also to measure the effect of the quality improvement intervention. Continuous quality improvement depends on determining what improves quality and what doesn’t by using good data to continually assess and reassess healthcare quality.

Most quality improvement programs use patient information gathered from insurance claims or medical bills—in other words, administrative data. There are many advantages to this type of data, the chief of which are there is a lot of it and it is easy and inexpensive to access.

But there are many disadvantages as well. Administrative data are intended to populate insurance bills and do not reflect clinical records. Specifically, administrative data are not clinically detailed enough to evaluate and measure quality of care, regardless of whether the measure is a process or outcomes measure. And although administrative data can be useful in measuring mortality rates, this type of data is not a strong tool for measuring morbidity, especially (as we shall see) complications. In short, studies show that administrative data are limited, inconsistent, and subject to misinterpretation when used to measure performance (Hall et al., 2007).

The Need for Clinical Data

The need for strong, robust, actionable data to measure and improve quality is what drove the American College of Surgeons to develop the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP), which collects information from patient’s medical charts—in other words, clinical data. With roots in a similar program developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, ACS NSQIP is the nation’s first and only risk-adjusted, clinical, outcomes-based program to measure and improve the quality of surgical care across specialties in the private sector.

Clinical data are more difficult and expensive to collect than are administrative data, but these challenges are far outweighed by the opportunity clinical data create to improve quality and reduce hospital costs. ACS NSQIP data are abstracted by trained Surgical Clinical Reviewers (SCRs) with a focused intent and explicit guidelines, providing more comprehensive and detailed information for quality improvement initiatives. The SCRs collect clinical data regarding patient demographics, preoperative risk factors and laboratory values, the operation and its outcome, and outcomes 30 days after the patient’s operation.

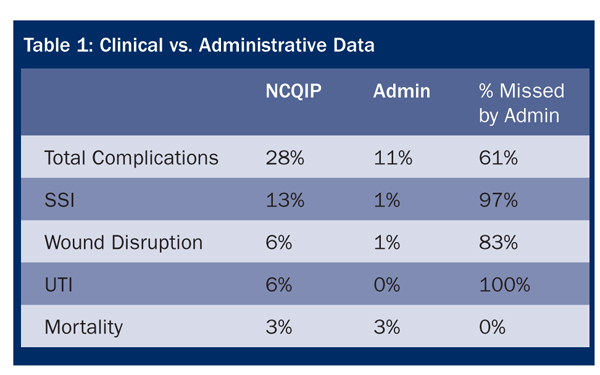

Studies have shown that clinical data are more detailed, robust, and informative than are administrative claims and billing data. In fact, when compared to clinical data, studies show administrative data are limited, inconsistent, and subject to misinterpretation when used to measure performance. For example, a study by researchers at Ohio State University Medical Center comparing clinical data and administrative data found that when compared with ACS NSQIP methodology using clinical data, a program using claims data missed 61% of total complications, including 97% of surgical site infections and 100% of urinary tract infections (Table 1) (Steinberg et al., 2008). Given that surgical site infections account for one in five hospital-acquired infections, leading to more than 8,000 deaths and some $10 billion in costs a year, accurate detection and measurement of these infections is critical to prevention efforts (Klevens et al., 2007).

In 2009, a study in the American Journal of Medical Quality found a common quality improvement program based on administrative data “missed or misclassified” several major complications that clinical data programs routinely catch (Davenport et al., 2009). The study concluded that clinical data are more useful for measuring and improving quality because of “significant limitations” of administrative data. Finally, a 2009 study in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that administrative data have limited “ability to account fully for illness severity” and it may “result in an inaccurate ascertainment of postoperative complications” (Gaferia et al.)

Reliability of Data

Administrative data are collected for the purpose of billing the patient and the payer and, therefore, represent only billable events that occur within the hospital. There can be conflicting motives in reporting these administrative data: on one hand, there is the desire to capture every possible use of resources and services for every possible event, which can lead to over-reporting; on the other hand, there is fear that over-reporting could bring accusations of fraud may encourage under-reporting. In either case, the way administrative data is collected may contribute to its inaccuracy and inconsistency (Ingraham, et al, 2010).

ACS NSQIP uses trained and audited data abstractors (SCRs) to collect robust, high-quality clinical data based on precise definitions.

Before collecting data for the hospital, SCRs must complete a two-day training session, which includes a program overview and details on data collection, including the sampling methods and specific information on variables and definitions. To achieve initial certification, SCRs must pass a post-test and achieve a minimum score on each of six online training modules.

After initial certification, ACS NSQIP supports SCRs through conference calls, online resources, and the ACS NSQIP annual conference. Inter-rater reliability audits are conducted through information collected by onsite reviews. Site reviewers examine operative logs to ensure correct sampling of cases as well as data collected from a sample of charts that are randomly selected and specifically identified to detect potential reporting errors. A disagreement rate greater than 5% for the individual site’s audit of variables collected or an individual variable within the overall program generates corrective action.

A recent analysis of inter-rater reliability of variables in the ACS NSQIP found that the reliability of the data was high from the inception and has only improved over time (3.15% disagreement in 2005 versus 1.56% disagreement in 2008) (Ingraham et al., 2010). Furthermore, the disagreement rates for variables identified as needing corrective action have improved over time, with the number of variables with disagreement rates greater than 5% falling from 26 variables in 2005 to two variables in 2008 (Shiloach et al., 2010).

Building Participant Confidence

The success of quality improvement programs relies, at least in part, on the willing participation of surgeons and other clinicians.

A major obstacle facing many “quality programs” is that surgeons are skeptical that administrative data can provide the basis for a fair and accurate assessment of the quality of the care they give. They would argue that billing data should no more be used to assess the quality of care than they should be used to chart a course for that care.

When surgeons lack confidence in the data, they may be reluctant—or even refuse—to participate in the quality improvement program. This is no small issue because surgeons, like many physicians, have historically rejected programs that are not based in evidence; this, in turn, has led some critics to charge that physicians resist being measured. In fact, surgeons, especially, are predisposed to measurement, provided they are confident that the measures are valid.

It’s one thing to participate in a quality improvement program, but quite another to act based on that program. If surgeons believe in the data, they are more likely to have confidence in the program and its recommendations. Due to the strength of ACS NSQIP’s data and scientific approach to measuring quality, surgeons, and other participants are confident in the reliability and accuracy of the program, which is critical to its effectiveness. In addition, since ACS NSQIP data take into account the health, age, and other factors that affect the patient’s condition, and as one of few quality improvement programs that accurately adjust for the risks facing the patient, surgeons are more confident that ACS NSQIP data provide a strong, equitable basis to compare quality of care. (The importance of adjusting for risk will be explored in the third article in this series).

What is true for any scientific inquiry is true for improving healthcare: the better the data, the more meaningful the results. As surgeons, nurses, and hospitals see that the program advances patient outcomes, they become increasingly confident that it can actually deliver on its promise to continuously improve quality. As the trend toward public reporting takes hold, continuously quality improvement will be noticed by patients, too.

Clifford Ko serves as director of the American College of Surgeons Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care. He is a practicing surgeon, who serves as professor of surgery and health services at UCLA Schools of Medicine and Public Health, director of UCLA’s Center for Surgical Outcomes and Quality, and a research scientist at RAND Corporation. He holds a medical degree, BA in biology, and MS in biological/medical ethics from the University of Chicago, and a MSHS in health service research from the University of California. Dr. Ko can be contacted at cko@facs.org.