That’s the way we do things around here!

July / August 2012

![]()

ISMP

That’s the way we do things around here!

Studies have long supported that an organization’s safety culture is the most critical, underlying predictor of accomplishments related to safety (Clarke, 1999; Randell, 2003; Zohar, 1980; Carroll et al., 2002; Scott et al., 2003). A multitude of definitions of safety culture exist, but none are more telling than “that’s the way we do things around here” (Wakefield et al., 2010). An organization’s culture encompasses observable customs, behavioral norms, stories, and rites that occur in the organization as well as the unobservable assumptions, values, beliefs, and ideas shared by groups within the organization. Culture is the most stable and significant force that shapes the way workers perceive the organization’s values and, in turn, how they think, behave, and approach their work (Gherardi & Nicolini, 2000; Permal-Wallag). It is the organization’s safety culture that produces social concepts regarding what is considered dangerous or safe, and what attitudes and behaviors toward risk, danger, and safety are appropriate (Permal-Wallag).

A number of survey instruments have been developed and used in organizations to assess and measure the safety culture (Sexton & Thomas; Singer et al., 2003; AHRQ). These surveys evaluate typical features of a safety culture, such as leadership, staffing, communication, and reporting. The results of the surveys are often used to identify strengths and weaknesses in the current culture.

A recent study by Wakefield et al. (2010) has taken culture surveys a step further, going beyond merely measuring aspects of a safety culture, to gaining an improved understanding of the factors that influence physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals (e.g., respiratory/physical/occupational therapists) to engage in patient-safety related behaviors associated with high-reliability (e.g., reporting hazards and errors, speaking out about risks, intervening when an error or at-risk behavior is witnessed, following safety guidelines)(Gaba, 2000).

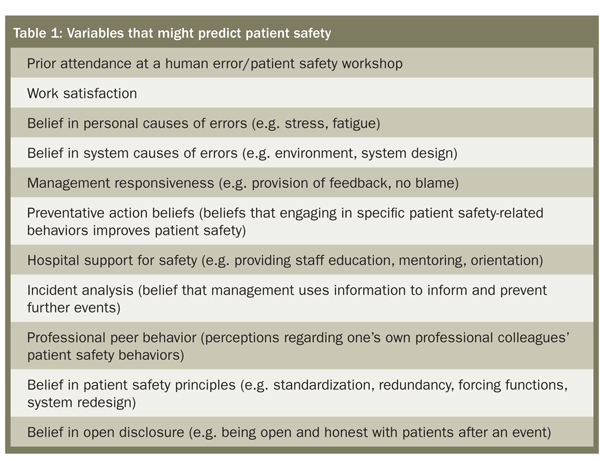

To conduct this study, a proven behavioral model was used to identify general factors that might influence the practitioner’s intent to engage in patient safety behaviors. Additional factors that might predict patient safety behavior were identified from the safety literature and focus groups. Based on these factors (Table 1), a survey instrument with 136 items was developed and administered to more than 5,000 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals in 37 hospitals located throughout Queensland, Australia.

The study found that the two strongest predictors of high-level patient safety behaviors for all healthcare workers are:

- Observed behaviors of professional peers (professional peer behavior)

- A genuine belief in the safety outcomes of the behaviors (preventive action beliefs).

When the different professional groups were compared, medical residents (referred to as junior doctors in the study) demonstrated the lowest intent to engage in patient safety behaviors. Attending physicians (referred to as senior doctors in the study) were 1.5 times more likely than medical residents to exhibit patient safety behaviors while experienced nurses (called senior nurses in the study) were 6 times more likely to exhibit these behaviors.

Compared to other study practitioners, medical residents were more likely to perceive blame as the result of an event, less likely to speak up when an error is made, and less likely to report positively about management. The authors note that the existing culture in academic medicine, which nurtures individual autonomy and competitiveness rather than collaboration and openness, may explain some of the differences between medical residents and other professional groups.

It follows from these findings that the influence of credible, clinical leaders who believe in, and are prepared to model, patient safety behaviors in the workplace, is key (Wakefield et al., 2010). When it comes to patient safety, actions truly speak louder than words. The study results make it clear that peer-to-peer mentorship at the work unit and facility level, with specific roles in modeling patient safety behaviors, are needed as guiding examples to encourage safe behavioral choices and foster a culture of safety within the organization. This includes physician-to-physician mentorship. If there is a visible commitment to safety within the organization that is evident in the behaviors of its members, it is more likely that safe work practices will be followed (Permal-Wallag).

So, always keep in mind that your professional peers are likely learning from your behaviors on a day-to-day basis, whether it involves taking a shortcut that is thought to be necessary at the time, or speaking up about a risk you observe. Patient safety—indeed, a culture of safety—begins with YOU leading by example.

This column was prepared by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), an independent, nonprofit charitable organization dedicated entirely to medication error prevention and safe medication use. Any reports described in this column were received through the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported online at www.ismp.org or by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE (800-324-5723). ISMP is a federally certified patient safety organization (PSO), providing legal protection and confidentiality for patient safety data and error reports it receives. Visit www.ismp.org for more information on ISMP’s medication safety newsletters and other risk reduction tools.

This article previously appeared in the ISMP Medication Safety Alert: Acute Care, February 24, 2011.