Shakespeare Was on Target: Neither a Borrower nor a Lender Be

September / October 2012

![]()

ISMP

Shakespeare Was on Target: Neither a Borrower nor a Lender Be

The phrase, “Neither a borrower nor a lender be,” originated from Shakespeare’s famous play, Hamlet (1603), during which Lord Polonius gives this advice to his son who is heading back to school. Because our world is different today, you may believe this advice is outdated and irrelevant. But when it comes to medication safety, Shakespeare’s advice is timeless; medications should never be borrowed from or lent to others.

His advice is simple enough to follow, but practitioners can be tempted to borrow a “missing medication” (a dose that should have been available) or the first dose of a new medication from another patient’s cassette, a discharged patient’s unused medications, or another patient care unit. Borrowing medications as a workaround to speed the process of administering medications due to inherent or excessive wait times associated with the pharmacy dispensing process increases the risk of an error.

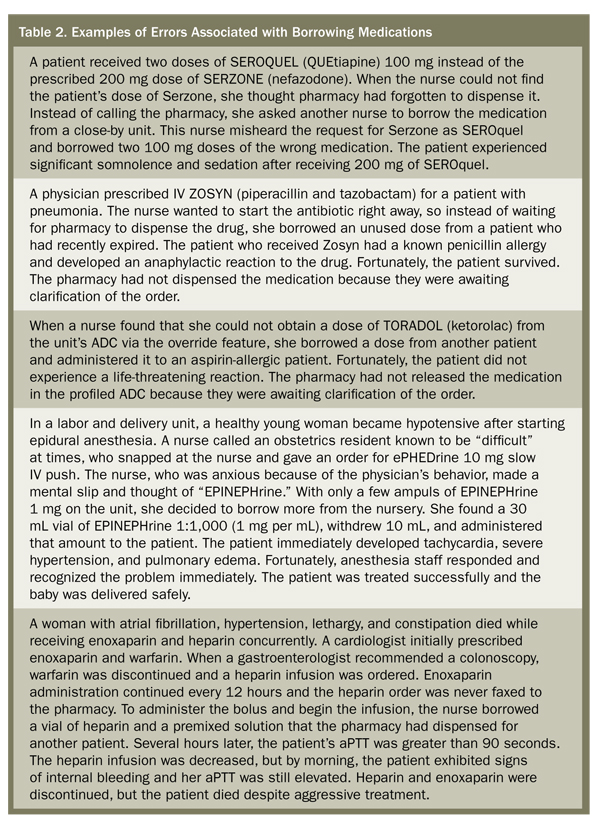

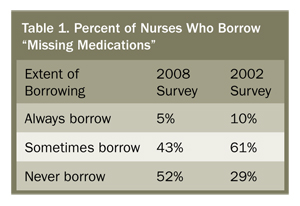

Lest you believe that profiled automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) and unit dose dispensing alone have sufficiently curtailed the practice of borrowing medications, a survey originally conducted in 2002 and repeated in 2008 (Table 1) found that almost half of the 1,296 nurses who participated in the most recent survey still borrowed medications when doses for their patients appeared to be missing on the unit (Cohen & Shastay, 2008). Table 2 describes just a few of the many errors that have been reported to ISMP as a result of borrowing medications (which can be similar to errors associated with removing medications from floor stock or ADCs before pharmacy review of the orders).

Because there are many opportunities for error, the ideal medication administration system is one in which there is more than one practitioner between the drug and the patient. For example, while screening orders, a pharmacist may detect a prescribing error such as an inappropriate dose, a drug allergy, or a drug-drug interaction. While checking medications before administration, a nurse may detect a pharmacy dispensing error. While reviewing the patient’s medication administration record (MAR), a physician may detect the inadvertent discontinuation of a drug.

Most pharmacies have a system of checks before medications are dispensed. Computer software helps screen the order for appropriateness and safety, and multiple staff members aid in preparing the medications and check them against the order before they are dispensed. However, this safety system is bypassed when doses are borrowed from other patients or obtained from an ADC before a pharmacist has screened the order. Thus, with borrowed medications, the system will not provide adequate checks to capture errors before they reach the patient.

Safe Practice Recommendations

Borrowing medications is not just a nursing problem; it’s a complex, interdisciplinary clinical issue that requires ongoing teamwork and excellent communication among nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare practitioners. Begin by assuming that borrowing of medications occurs in your hospital and consider the following four-pronged approach to address this issue.

1. Remedy the reasons for borrowing.

Prohibition against borrowing medications via policy is not enough to ensure patient safety, as the reasons for this behavior are often rooted in system deficiencies. Learn why nurses and other practitioners may borrow medications from unauthorized sources and address these issues in a collaborative manner. If turnaround time for dispensing medications (or review of orders to allow access to medications in ADCs) is perceived to be an issue, set up measures to identify the scope of the problem, address vulnerabilities, and gain consensus among nurses, pharmacists, physicians, and hospital leadership regarding acceptable time frames for drug delivery or order review. Uncover and address misconceptions about the clinical significance of providing therapy within the acceptable time frame for starting new drug therapy. If awaiting order clarification, pharmacists should contact the nurse to communicate the reason for a delay.

2. Decrease staff tolerance.

Ensure nurses and other practitioners understand the risks and consequences of borrowing medications, and ensure pharmacists understand the risks and consequences of delayed order review and dispensing of medications. Encourage reporting of conditions that contribute to delayed order review and dispensing, which may encourage and reward the practice of borrowing medications. Use this information to improve the medication-use system.

3. Reason(s) for missing medications.

Missing doses are an inconvenience and could be related to system problems with restocking of ADCs, or delivery to patient care units. However, a medication can be missing or not available for other reasons:

- The medication was already given but not documented on the MAR.

- The dose was given on another unit.

- The medication time or frequency was scheduled incorrectly and is being reviewed.

- The order was incorrectly interpreted or mis-transcribed onto the MAR.

- The medication was not dispensed by pharmacy because of a safety problem.

- An additional dose in the 24-hour cart fill was used to replace a previously dropped dose or a dose that had been vomited.

- The drug was misplaced (e.g., removed from the tube and left at the station).

- Pharmacy never received the order.

- A discontinued drug is still on the MAR.

4. Eliminate unauthorized access to drugs.

Discourage the accumulation of discontinued or unused medications in patient care units. Provide a secure container or ADC compartment for staff to place medications from discharged or expired patients as well as other discontinued or unused medications. Conduct frequent pharmacy rounds to collect these medications (including refrigerated items). Use profiled ADCs and establish stringent criteria for removal of medications. Monitor override reports for appropriateness.

This column was prepared by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), an independent, nonprofit charitable organization dedicated entirely to medication error prevention and safe medication use. Any reports described in this column were received through the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program. Errors, close calls, or hazardous conditions may be reported online at www.ismp.org or by calling 800-FAIL-SAFE (800-324-5723). ISMP is a federally certified patient safety organization (PSO), providing legal protection and confidentiality for patient safety data and error reports it receives. Visit www.ismp.org for more information on ISMP’s medication safety newsletters and other risk reduction tools.

This article previously appeared in the ISMP Medication Safety Alert: Acute Care, 14(23), November 19, 2009.

References