Safer PCA Therapy

March/April 2011

Safer PCA Therapy

Patient Safety Benefits of Continuous Respiratory Rate and End Tidal Monitoring

The following interviews were adapted from a November 12, 2010, webcast, “Safer PCA Therapy,” that explored the application of continuous monitoring for patients receiving opioids, most typically using patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). Information on the following topics is presented:

- Current state and future trends of advanced monitoring techniques for patients on opioids

- Expert perspectives on the advantages and disadvantages of various types of monitoring for patients receiving PCA or patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA), including pulse oximetry and capnography

- A unique central surveillance monitoring system that communicates capnography and oxygen saturation alarms directly to the caregivers to improve the safety of the monitoring system.

The goals of these efforts are to help improve opioid administration safety; reduce medical, surgical, nursing response times to critical events; identify the roles of the various team members; and review interventions to help prevent patients from experiencing opioid-related respiratory depression.

Dr. Vanderveen: In October 2006, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) board of directors hosted a workshop on PCA and opioid administration that was attended by more than 100 clinicians, scientists, medical industry representatives. What were some of the key takeaways?

|

Table 1

2006 APSF Workshop Report

2009 APSF Editorial

|

Dr. Stoelting: As noted in the workshop report authored by Matthew B. Weinger, MD, of Vanderbilt, there is a significant, under-appreciated risk of serious injury from drug-induced respiratory depression in the post-operative period. While some patients, notably those with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) appear to be at higher risk, there is still a low but unpredictable incidence of respiratory depression in healthy, young patients. More widespread use of available monitors would prevent a significant number of these adverse events. The report contained several recommendations from the workshop to address these issues (Table 1)(Weinger, 2006-2007).

In 2009 Dr. Weinger and I published an editorial on the continued danger of post-operative opioids (Stoelting and Weinger, Summer 2009). Adverse events related to drug-induced respiratory depression continued to come to our attention, including:

- Events in which the monitoring of oxygenation and ventilation was either absent or inadequate

- Failure to recognize at-risk patients, specifically those at risk for OSA

- Use of standardized protocols that were not being tailored to the individual patient

- Supplemental oxygen being used routinely, rather than when it was medically necessary.

Our recommendations to address these events are also shown in Table 1 (Stoelting and Weinger, Summer 2009).

Dr. Vanderveen: Dr. Mitchell, your health system decided to implement continuous monitoring. Soon after the first implementation, you had a case that illustrates the need for such monitoring. Could you take us through the details?

Dr. Mitchell: Sisters of Mercy is a very large integrated provider of healthcare with about 28 hospitals. In our 10 largest facilities, we replaced all of our pumps and PCAs with a single product that combines large-volume, syringe, PCA, and respiratory monitoring modules. We have now embarked on a second phase to get the system out to our smaller critical access hospitals.

A few weeks after implementation we received an interesting case report. An athletic, non-snorer, mid-30s father of two beautiful kids came in for knee surgery after persistently impersonating the outstanding athlete he used to be in high school.

Following the procedure he was placed on PCA. He was not particularly thrilled to have a CO2 monitor under his nose, but his anxiety about having his first major operation helped us convince him, and he gave into our explanation of protecting his safety. He wore it more easily after an additional dose of opioid.

The nurse assigned to him did an assessment that showed everything was normal, and scheduled a follow-up check within the hour. About a half an hour later, the PCA respiratory low rate alarm drew her back to his room early. The patient was deeply sedated, breathing very slowly and shallowly. The pulse oximetry reading was still within normal limits, although at the low end of normal. Fortunately, he was able to be sufficiently aroused with manual stimuli to regain his respiratory drive and return to normal CO2 levels and respiratory rate (RR). With close observation, he was able to avoid being transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and was subsequently discharged on time.

After investigating the event and discussing it with the patient, our best explanation is still that he was really totally naïve to opioids and had had a dramatic, unexpected effect from fairly standard doses of narcotic. Even though we couldn’t totally rule out OSA, he had no history or family history. Obviously he was lucky to have been monitored continuously by protocol, or we’d be giving a very different case report today.

|

Robert K. Stoelting, MD Glenn Mitchell, MD, MPH, FACEP Joan Kohorst, MA, RRT Ann Holmes, MS, RN Cynthia Nichols, PhD, FAASM, CBSM |

In my experience, the confidence and commitment of the caregiver who is explaining it to them is absolutely related to the acceptance of the patient who has some anxiety about having that monitor below their nose. If whoever is doing the explanation and coaching is committed to the safety and the good effects for the patient, the patient almost always figures out that they really do need this tool and are fine with it.

Dr. Vanderveen: Has post-operative pain management always been as dangerous as it seems today? What’s your perspective?

Dr. Mitchell: I’m not sure we have enough knowledge about how dangerous the administration of PCA really is today. In a small study we found that almost 33% of patients had significant respiratory pauses that could contribute to subclinical brain injury. This could be a new area of investigation in the neurosciences. In the worst case, we may have been doing small amounts of subclinical harm in a potentially additive way. Logically, our approach to this theoretical problem can only be to try to eliminate respiratory depression and significant pauses whenever possible. We need to better understand this therapy’s risks versus benefits with and without monitoring.

Dr. Vanderveen: To date the evidence for better patient outcomes with monitoring for PCA and epidural opioids is somewhat limited. Is more widespread adoption of continuous monitoring dependent on prospective randomized clinical trials? Or is this more of an intuitive example analogous to proposing a study of skydivers, some with and some without parachutes?

Dr. Mitchell: Studies do need to take place to fully document the effects. But in the meantime, I’m in agreement with the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) and the ASPF that we certainly should be doing continuous monitoring in most circumstances when a PCA pump is in use.

Dr. Vanderveen: Joan, there are currently two types of monitoring for post-op patients on opioids. As an experienced respiratory therapist (RT), would you summarize the advantages and disadvantages of each?

Kohorst: Monitoring a patient’s oxygenation and ventilation are both very important. As noted by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force, “Monitoring with pulse oximetry and capnography is standard of care and has resulted in remarkable reductions in patients’ morbidity and mortality.” The capabilities of each are summarized in Table 2.

|

Table 2

Pulse Oximetry

Capnography

|

Dr. Vanderveen: What is your policy about the use of routine supplemental oxygen and how it might interfere with true respiratory status?

Kohorst: Patient status can change very rapidly. The vital signs and monitoring data that the nurse obtained can change as she’s walking out of the room. Intermittent monitoring and vital signs won’t capture those rapid changes. Continuous monitoring gives a much truer picture of the patient’s level of sedation when there’s no one taking their vital signs or asking them questions.

Again, oxygen is a drug. Patients should have a clinical indication for supplemental oxygen before it is administered. No clinician would give a patient dopamine or insulin “just in case.” You shouldn’t give a patient oxygen “just in case,” either. If only pulse oximetry is used to monitor post-operative patients, supplemental oxygen will delay the detection of respiratory depression.

Dr. Vanderveen: I’ve heard that observed RRs often do not reflect true rates of breathing, which are a key determinant of the patient’s respiratory status. What is your experience?

Kohorst: RR is just one component of effective (minute) ventilation. We typically count the number of times the patient’s chest rises and falls for 10 seconds and then multiply that by 6 to get the breaths per minute (bpm). Average normal RR is 8 to 12 bpm.

Observation of chest expansion doesn’t give you enough information to make sure that that patient is being adequately ventilated because it’s only looking at the chest movement. It’s not looking at the depth and adequacy of ventilation.

The other component of effective ventilation is tidal volume (the volume of air inhaled and exhaled with each resting breath). Average adult tidal volume is about 500mL. If the tidal volume is decreased, the patient is not ventilating, not moving enough air into and out of the lungs. End tidal CO2 (EtCO2) monitoring will detect this immediately.

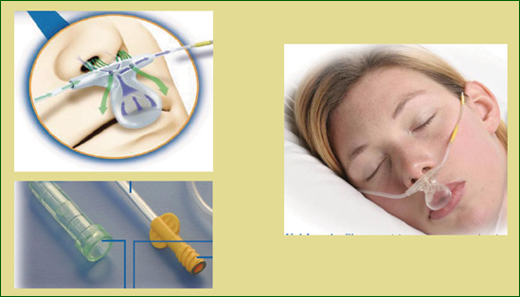

As shown in Figure 1, the sampling line is similar to a nasal cannula, with the prongs in the patient’s nares and a scoop over the patient’s mouth, to capture exhaled gas in case they breathe by mouth. CO2 is measured through the prongs or the scoop. The sample line also can be attached to an oxygen flow meter and provide oxygen with a rate of up to five liters per minute.

In the monitor’s sample chamber, the CO2 in exhaled gas is detected by a very narrow infrared radiation beam. The beam is not interfered with by the presence of supplemental oxygen, water vapor, or anesthetic gases. The capnographic wave form shown on the monitor allows a clinician to actually see the level of carbon dioxide throughout the respiratory cycle.

Based on some of the early findings related to PCA and pain management, Mercy has established a pain management expert panel, which includes caregivers from across the system. They are currently reviewing order sets, policies, monitoring requirements, nursing assessment components, and nursing responses to alarms. The result will be recommendations for order sets designed to take the patient’s opioid tolerance into consideration, as well as standardization of pain management policies across the system. We hope to have our recommendations ready to submit shortly.

Dr. Vanderveen: Since capnography is new to many nurses, what training do your nurses, patients, and family members receive in the Sisters of Mercy system?

Kohorst: For most of our medical-surgical nurses at Sisters of Mercy, training in the new continuous respiratory monitoring technology is essential. Nurses are trained on the what, how, and why of the new technology through course materials, demonstrations, return demonstrations and competency verification. RTs act as resources for the nurses with questions about the technology or patient issues.

Since capnographic monitoring (end-tidal CO2 and RR) is new to most medical-surgical nurses, new policies and procedures must be created. The policies should include an assessment component and an alarm response matrix. The response matrix could include guidance on “what to do when the alarm sounds”: for example, position the patient to open the airway, stimulate the patient, encourage deep breathing, and assist breathing, if needed. Guidance on when to call the rapid response team, when to contact RTs and/or the physician, when to decrease the narcotic dose or discontinue the medication, and when and how much naloxone (Narcan) to administer could also be included in the monitoring policy.

Patient and family education materials explaining the safety benefits of EtCO2 monitoring should be provided for all individuals receiving pain management via PCA. If you can educate patients before they go to surgery, they will be more likely to understand the importance of wearing the monitor sample line after surgery.

In most of our facilities, the PCA device is set up in post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The nurse uses the PCA pump to provide continuous pain management for the patient before they move them to the floor. The EtCO2 monitor is hooked up to the PCA device while they’re in the PACU. Monitoring in the PACU will give you baseline EtCO2 data, which can be compared to results obtained once the patient does get to the floor. The baseline and comparison data will help the caregiver determine if the EtCO2 alert limits are set appropriately for the patient. Once the patient gets into the room on the floor, the nurse on the floor just has to give the button to the patient. The EtCO2 information is already in the device waiting for them.

Patients who have just been transferred out of the PACU to the floor need to be monitored. That patient may have received some additional pain medication to keep them comfortable during the transport, or they may still have some anesthesia on board. The EtCO2 monitor will alarm if the patient experiences respiratory depression and the alarm will bring the caregiver back to the bedside so that a more serious event can be prevented.

Dr. Vanderveen: Dr. Mitchell, the technology used at Sisters of Mercy combines the PCA pump and patient monitoring modules on a single platform and can automatically pause opioid administration if the oxygenation or RR drop below predetermined levels. How important is this feature?

Dr. Mitchell: Engineering controls are nearly always superior to any educational, observational, or voluntary safety measures. I insisted on the automatic pause feature as a vendor-choice criterion when we invested in smart pump technology. I’m convinced that automated monitoring and pause are reducing the opportunities we have to harm a patient.

Dr. Vanderveen: Have you been able to determine which patients on opioids do or do not need to be continuously monitored, or the criteria for discontinuing the monitoring?

Dr. Mitchell: After 30 years of practice, I’m still surprised on too many occasions to be comfortable with the current screening criteria. From my point of view, any agent that can cause serious respiratory depression is a candidate for instituting continuous monitoring. In our facilities monitoring isn’t discontinued unless the patient cannot tolerate the equipment even after education and coaching, demonstrates decreasing medication requirements and lack of alerts and alarms, and is clinically improving after 24 hours.

Dr. Vanderveen: Munson Medical Center in Traverse City, Michigan, has been using PCA technology with integrated EtCO2 monitoring for about 2 years. Can you tell us how you use the system on your post-operative general medical-surgical unit, and about your unique central surveillance monitoring system?

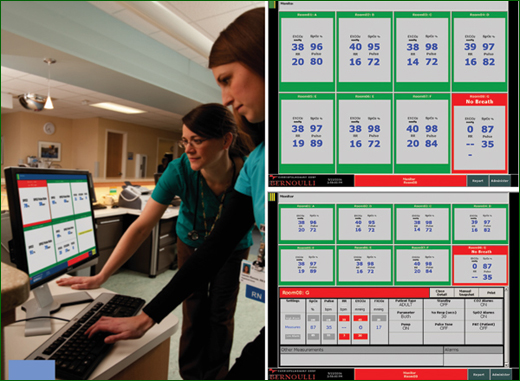

Holmes: When we looked at monitoring, it was very important to me as a manager that the system would alarm not only at the bedside but also at a central monitor and the nurse’s pager, cell phone, or some other device.

As shown in Figure 2, at our central station we can monitor up to 12 patients in real time. If a patient sets off an alarm with the EtCO2 or SpO2 monitor, the alarm sounds at the station and also goes to the nurse’s pocket pager or portable phone. The PCA infusion is automatically paused in the event an alarm is activated. Table 3 (on page 37) shows the patients who are monitored.

We’ve experienced really high patient compliance with EtCO2 monitoring. Once we’ve explained how important it is, most patients do very well with it. The most important thing to remember is that continuous respiratory monitoring has not replaced nurses at the bedside.

Dr. Vanderveen: Dr. Mitchell reviewed a case that illustrated the value of the continuous monitoring at his hospital. Do you have a similar case that illustrates your experience?

Holmes: We probably could do case studies on four to five patients per week. In one case, a 58-year-old man was admitted postoperatively from the PACU after he had a decompressive lumbar laminectomy with BAK cages. The patient’s PCA setting was Dilaudid 1 milligram, a lock-out interval of 6 minutes, a 4-hour dose limit of 30 mg, and a continuous infusion of 0.2 mg/hr—which is typical for most of our patients.

The patient was admitted to the unit with a pain level of 5 and RR of 12. Routine assessments were done per protocol. About 2 hours later, the EtCO2 began alarming at the central monitor, bedside, and nurse’s pager. The patient’s RR had decreased to about 4.

The nurse assessed the patient and easily awakened him by calling his name. While continuing to assess him, she learned that he had been self-administering his Dilaudid every 10 minutes when his wife woke him up to remind him to hit his button. He said his pain score was 2 and he felt good. The nurse educated the patient and family again as to appropriate use of the PCA.

Three minutes after she left the room, she was again notified by pager that his RR had dipped down to 5, and she returned to his room. In our PCA protocol, nurses have the ability to discontinue the continuous infusion, and she did. She then raised the patient’s head in the bed, made sure he was comfortable and kept aroused, and checked him frequently. With the continuous infusion discontinued, he continued to have good pain control over the next 6 hours.

Dr. Vanderveen: What policies and procedures were developed and are you using the central surveillance monitoring reports with your nurses, your RTs, and your medical staff?

Holmes: Policies and procedures were put together in a joint effort with respiratory therapy, intensivists, sleep study physician, pharmacy and nurses. These include routine PCA orders, a routine order set for your SpO2 and EtCO2 monitoring, criteria for discontinuing monitoring and a reversal agent protocol. We also made sure that our oxygen protocol was aligned with these.

With our central monitoring system we also can pull up a report that shows all of the events that happened to a given patient during a given time period. This report is printed at any time when we want to follow up on a patient and also goes on their medical record. We also use this to determine who can come off the monitoring, rather than relying on memory as to how many alarms the patient has had.

We have an electronic charting system. The nurses are alerted every 8 hours to document what has happened with a patient, whether or not they had episodes, and if they did, what they did for those events.

Dr. Vanderveen: How did your hospital set up the alarm limits, the low RRs, the no breath limits specifically, and the PCA pause limits? This can be very important in reducing nuisance alarms for the nursing staff, the patients, and the family.

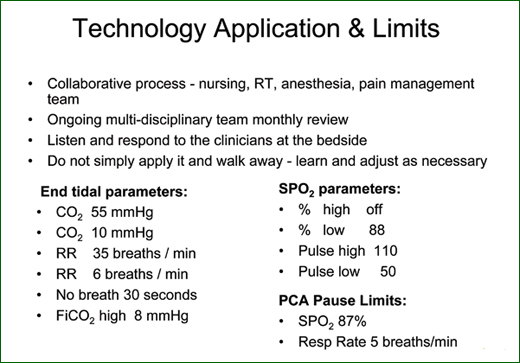

Holmes: Nuisance alarms were something we were very, very concerned about, but we found that that is not an issue at all. Our parameters (Figure 3) were established by a multi-disciplinary team comprising nursing, respiratory therapy, anesthesia, and pain management. A multi-disciplinary team meets monthly then to look at our alarms and CQI data with regard to the alarm settings, dosing limits, and nurses trying to override the limits.

We learn from almost every event and make any necessary adjustments. For example, bariatric surgery patients often have an elevated heart rate when they’re ambulating in post-operative care. If necessary for a specific patient, we will call the physician and ask for orders to change the high limit on pulse rate. We don’t change any of our alarm settings without a physician’s order.

Kohorst: The first hospital in our system to use the respiratory monitors set up their low RR alarm default at 8. By policy they were required to set their high CO2 alarm at 50. There were lots and lots of nuisance alerts, which led to some significant satisfaction issues with the caregivers and patients.

Based on our analysis of data that we’ve been able to obtain, we’ve changed the default alarm settings to a low RR of 6 and a high CO2 level of 60. Of course, those can be adjusted based on patient requirements and physician order, but it has decreased the number of nuisance alerts significantly.

Dr. Mitchell: I still find resistance, especially in physician staffs, to setting the rate alarm soft limit at 6 bpm to begin with. I spoke to people in Boston recently who insisted they were going to begin the PCA pump rate alarm at a limit of 10 bpm, because they wanted to catch every possible bad event. I couldn’t convince them otherwise. I just want to be sure everyone understands that that’s going to result in a significant amount of nuisance alarms. I breathe at 7 bpm when I’m asleep, so I believe 6 bpm is still a sensitive measure for the average patient.

Holmes: At first the nursing staff was reluctant to have yet another piece of new equipment to incorporate into their practice. But once we began using the monitor, we were amazed at how many patients had decreased RRs and oxygen saturation. This demonstrated to the nurses how important monitoring really was.

Investing in the technology really supports clinical decision-making and strengthens a culture of safety. We were able to treat patients who had diagnosed, untreated sleep apnea on the medical-surgical floors and found that the outcomes were not any different from when they were treated in an ICU.

We were very happy to be following the APSF recommendations, because we also knew that opioid-related adverse events were happening. We wanted to make sure that this didn’t happen to any of our patients. Continuous monitoring also allowed us to use higher doses of narcotics for patients who weren’t getting good pain relief.

Dr. Vanderveen: Dr. Nichols, Your training is in the field of sleep medicine and research, as well as care of the bariatric patient. Can you explain the associated risk of respiratory depression among these patients?

Dr. Nichols: Bariatric surgery patients often have a known diagnosis of OSA, but it is also common to find people with OSA who are undiagnosed prior to bariatric surgery. This occurs particularly in individuals who live alone and have no bed partner to report observations, and in individuals who deny symptoms such as sleepiness or snoring. An elevated body mass index is a risk factor for restricted breathing in the bariatric patient, even if they do not have a diagnosis of sleep apnea.

In OSA, repetitive episodes of airway obstruction are caused when the upper airway muscles relax, which occurs as you go to sleep. Normally, when a person obstructs during breathing, a protective mechanism activates the central nervous system and arouses the patient.

|

Table 4

|

In post-operative pain management, however, the side effects of opioid medications increase upper airway resistance, reduce the rate and depth of breathing, and blunt the arousal response. Opioids also blunt the normal ventilatory response to CO2. When those side effects are superimposed upon an already restricted airway, it increases the risk of post-operative morbidity and mortality in people with untreated or under-treated OSA.

Dr. Vanderveen: You and your team recently submitted an abstract, which was accepted, published, and subsequently developed into a poster presentation at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery meeting in May 2010. There were some interesting findings following the implementation of continuous monitoring, such as trends towards more appropriate nursing intervention and a decreased need for ICU care without compromising patient safety.

Dr. Nichols: Prior to the implementation of continuous respiratory monitoring in the postoperative surgical unit, patients with suspected or known sleep disorder breathing were sent directly to the ICU or to the ICU step-down unit postoperatively, due to concerns about the risk of opioid-related respiratory depression. We want to make sure that the right patients are in the ICU beds, with the goal of both improving patient safety and being cost effective. The cost to monitor a patient on the postoperative medical-surgical unit is 54% less than in the ICU.

The implementation of this system has reduced the ICU and step-down census of post-operative patients by approximately two patients per day. That means two patients per day who truly need the critical care are receiving it, and the ICU and the step-down beds are not occupied by patients with sleep apnea who simply require additional respiratory monitoring. We demonstrated that this could be done safely on medical-surgical floor with continuous respiratory monitoring. Our preliminary conclusions are shown in Table 4.

Tim Vanderveen is vice president of CareFusion’s Center for Safety and Clinical Excellence in San Diego, California.

References

|

Safer PCA Therapy – Additional Information

APSF does not write standards or guidelines. APSF makes recommendations. Our goal is to create awareness of safety issues and provide education. Our hope is that healthcare professionals, hospitals, anesthesia groups, national organizations, such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists will actually eventually support, endorse and adopt these recommendations.

The monitored subjects were consecutive admissions to a postoperative surgical unit. We did not include the ICU step-down admissions, because after we implemented continuous monitoring, the pulmonary and critical care physicians were so impressed with the technology, they concluded that patients could be at least as safe on the medical/surgical unit than if they were in the ICU. Outcomes data showed there were no significant differences between patients on the medical/surgical units vs. the ICU in the more severe outcomes. What we did find, which was very exciting, was that the interventions changed between baseline and monitored. These items were significant:

Dr. Mitchell: Our approach was to use medical-surgical vs. ICU costs and a root cause analysis from a bad outcome. That helped us a lot, because settlements can cost nearly the same as putting in the pumps. |