Reducing the Incidence of Uncontrolled Hypertension Through Self-Measured Blood Pressure Monitoring

A Quality Improvement Project at A & M Healthcare Clinic

By Janet M. Pitt, MSN, AGNP-C

Abstract

Background: Hypertension is one of the most commonly seen issues in primary care. The total yearly economic burden of complications and comorbidities associated with hypertension is in excess of $316 billion, with $51 billion of that attributed specifically to hypertension (Kirkland et al., 2018; Merai et al., 2016). Oklahoma ranks as one of the worst states with regard to hypertension-related mortality. The primary care setting is the perfect venue to examine strategies and employ best practices to reduce rates of hypertension and subsequent disability and death.

Aims: Using the Target: BP framework and the Healthy People 2020 initiative, the aim of this quality improvement project was to reduce the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension by 10% in a given patient population at A & M Healthcare Clinic in Tulsa, Oklahoma, over the course of 12 weeks.

Methods: Patients who chose to participate in the quality improvement project were given an automated upper arm blood pressure device to use at home. Patients were trained in the use of self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SMBP) and were instructed to measure and record their blood pressure on a designated blood pressure log in the morning and evening; this would be done for at least three days per week for a minimum duration of four weeks and a maximum duration of 12 weeks. At enrollment, patients completed the Hill-Bone Medication Adherence Scale (HB-MAS). They repeated the scale every four weeks until their blood pressure was at goal, or until the end of the 12-week project period. At the end of the project period, all blood pressure logs and patient devices were collected, and logs were analyzed for average blood pressures and scores on the HB-MAS.

Results: A total of 21 people participated in the quality improvement project, ranging in age from 30 to 60 years. Final blood pressure readings revealed 50% of patients with a reduction in average systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more, and 6.3% with normal blood pressure.

Final scores on the HB-MAS showed 23.8% of participants with the same initial and final score, 47.6% of participants with a higher final score indicating increased medication compliance, 4.8% of participants with a lower final score indicating decreased medication compliance, and 23.8% of participants who did not follow up after the initial consultation.

Conclusion: Overall, 57.2% of participants had a reduction in average systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more, far surpassing the aim of reducing the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension by 10% in a given participant group. These results show that the addition of SMBP was an effective intervention to help reduce rates of uncontrolled hypertension in this participant population.

Keywords: Hypertension, self-measured blood pressure (SMBP), quality improvement project, Hill-Bone Medication Adherence Scale.

Description of the problem

Hypertension is one of the most prominent issues seen in the primary care setting. The total economic burden of complications and comorbidities associated with hypertension is in excess of $316 billion, with $51 billion of that attributed specifically to hypertension (Kirkland et al., 2018; Merai et al., 2016). More than 100 million people from varying geographic settings and demographic subpopulations have been diagnosed with hypertension, making it one of the most clinically significant issues facing the adult population (American Heart Association [AHA], 2018; Breaux-Shropshire et al., 2015). The prevalence of hypertension increases with age and is more commonly diagnosed in persons over 40 (America’s Health Rankings, 2018; Fryar et al., 2017). Reducing the incidence of hypertension in the clinical setting can significantly reduce the risk of subsequent illness, disability, and mortality (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2019).

Background and significance

Oklahoma ranks higher than the national average for premature death and is the tenth state overall for rates of mortality related to hypertension (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). In 2018, among the top 10 causes of death in Oklahoma were heart disease and stroke, conditions that are both strongly linked to uncontrolled hypertension (America’s Health Rankings, 2018). One of the main foci of the Healthy People 2020 objectives is to reduce rates of uncontrolled hypertension (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2020b). The goals stemming from this initiative are slated to be continued for the next 10 years with the Healthy People 2030 initiative, further proving that hypertension is an issue of great concern for the nation overall (ODPHP, 2020a). Rates of hypertension in Oklahoma are consistently 5%–10% higher than the national average (America’s Health Rankings, 2018). The ZIP code in which this project site clinic resides ranks 38 out of 40 across nine quality indicators and has one of Tulsa County’s highest death rates, lowest average life expectancy, and lowest number of primary care providers (Tulsa Health Department, 2018). The project site clinic serves a primarily low-income population ages 18–90, the majority of whom are African American (A. Williams, personal communication, April 7, 2020). African Americans are over 20% more likely to develop hypertension and related comorbidities as compared to persons of white, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American descent (Fryar et al., 2017; Kaiser Permanente, 2018).

Using the Target: BP framework from the AHA, the 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA clinical practice guidelines for hypertension, and the benchmarks from the Healthy People 2020 initiative, this quality improvement project will examine the relationship between SMBP and average blood pressure (Target: BP, 2016; Whelton et al., 2018; ODPHP, 2020b).

Aims

The purpose of this project is to implement a standardized method for hypertension diagnosis, treatment, and management, to aid in the early recognition and treatment of hypertension, thereby reducing the number of patients affected and subsequent comorbidities and improving the overall health of the specified patient population. The overarching aim of this project is to reduce the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension by 10% over the course of 12 weeks through early identification, treatment, and patient engagement using the Target: BP framework, the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines, and the benchmarks from the Healthy People 2020 initiative (AHA, 2018; Whelton et al., 2018; ODPHP, 2020b).

Literature review

A large percentage of patients lack knowledge and understanding of their blood pressure goal and of the long-term effects that hypertension has on their health and quality/quantity of life. In addition, they lack adequate education on how pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments help them achieve their blood pressure goals (Jo et al., 2019). Literature suggests that the use of SMBP in conjunction with typical blood pressure management strategies helps to increase patients’ awareness of their blood pressure goals, and when used appropriately and consistently, can help to decrease overall blood pressure results (Breaux-Shropshire et al., 2015; Fletcher et al., 2016; Qi et al., 2017).

In a study of 7,751 patients, researchers reported that the addition of SMBP increased goal awareness by 24%, increased percentage of patients who achieved their blood pressure goal by 27%, and decreased medication non-adherence by 61% (Jo et al., 2019). SMBP is also reported to be a better predictor of how patients will fare with regard to long-term risk for comorbid conditions and health outcomes than the use of in-office measurements alone (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2020). SMBP monitoring is a cost-effective addition to office measurement and can provide useful information about blood pressure at different times of day. This type of therapy is useful to assist in the accurate and timely diagnosis of hypertension because it eliminates false high readings associated with white-coat hypertension (George & MacDonald, 2015).

Methods

Patients between the ages of 30 and 60 with a diagnosis of hypertension had the opportunity to participate in a quality improvement (QI) project to help to determine if SMBP is useful for providers in diagnosing and treating hypertension. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients age 30–60, English speaking, with a diagnosis of hypertension, who consented to participate. Exclusion criteria included patients less than 30 or greater than 60 years of age, patients who did not speak English, women who were pregnant or lactating, and patients with conditions prohibiting blood pressure measurement on the upper portion of the arm. Participants were recruited using an information sheet with details about the project, which was distributed via both the patient portal of the electronic medical record and through face-to-face visits.

Once several patients opted to participate in the QI project, the direct care staff were trained to train patients on the use of SMBP. Direct care staff received a 30-minute in-service in which they watched a three-minute video from the AHA on how to measure blood pressure at home. They received instruction on the operation and calibration of the automated blood pressure devices. They were instructed on how to choose the appropriate size blood pressure cuff for participants, and they were instructed on how to fill out the blood pressure log and the HB-MAS (Kim et al., 2000). Each direct care staff member performed a return demonstration of these elements before being checked off as a participant trainer.

Training for participants included the same elements: the three-minute video from the AHA describing how to measure blood pressure at home, instructions on how to operate the automated device, instructions on how to record blood pressure readings on the log, and when to return to the clinic for their next follow-up appointment. Patients were able to check out a calibrated blood pressure device from the clinic. They were instructed to measure their blood pressure at least three times a week, measuring it twice in the morning and in the evening. Each measurement was to be taken in succession after a one-minute rest period. Patients were instructed to record all readings on a blood pressure log sheet from the Target: BP toolkit (Target: BP, 2016). The HB-MAS was administered to the patients at week 1 and then every four weeks that they remained as a participant in the project (Kim et al., 2000).

At the end of the participation period, each patient was scheduled to return to the clinic for a final follow-up visit. The participants were instructed to bring the blood pressure device and all blood pressure logs with them. The blood pressure logs for each patient were analyzed for initial blood pressure reading, final blood pressure reading, and average blood pressure readings to see if there was a reduction in blood pressure. The final logs were compiled, and the averages compared across all participants to determine if the goal of reducing the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension in a given participant population by 10% was met.

Data analysis

Data sets for each participant included identification number, age, race, sex, initial and final blood pressure averages, and initial and final results of the HB-MAS. All data sets were input into IBM SPSS® Statistics Data Editor software and analyzed by the project coordinator. Statistical tests performed using this data included frequencies, crosstabs, descriptives, and paired sample T-tests (see Appendix A).

Findings

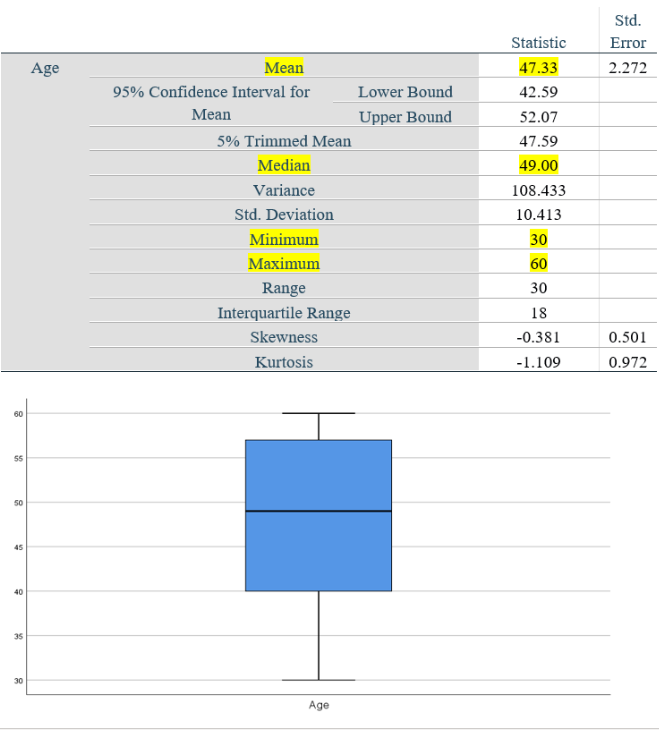

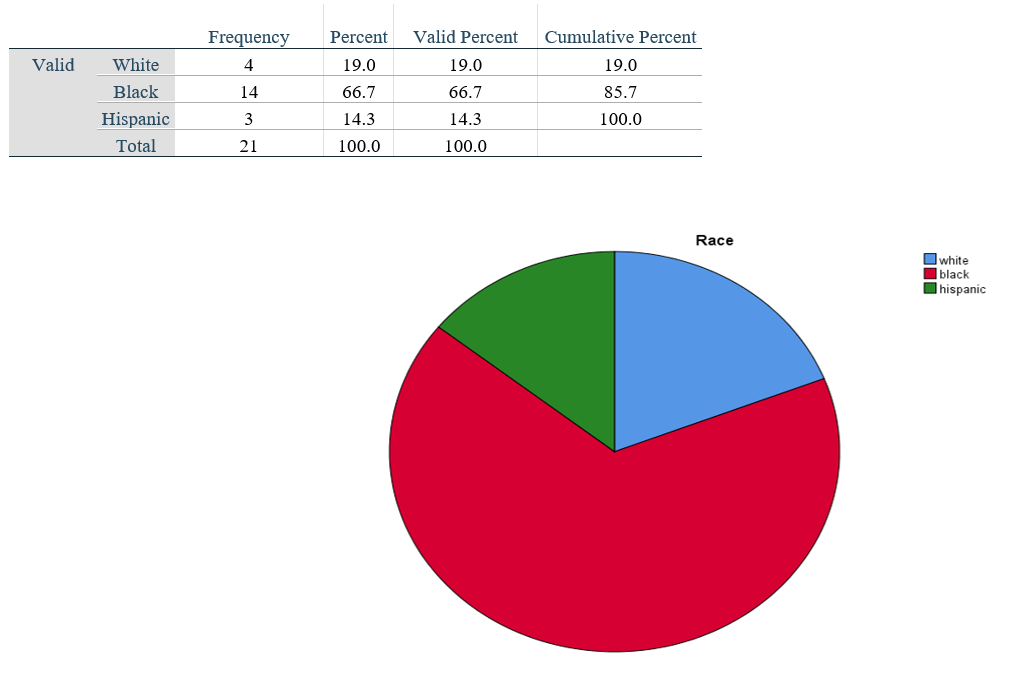

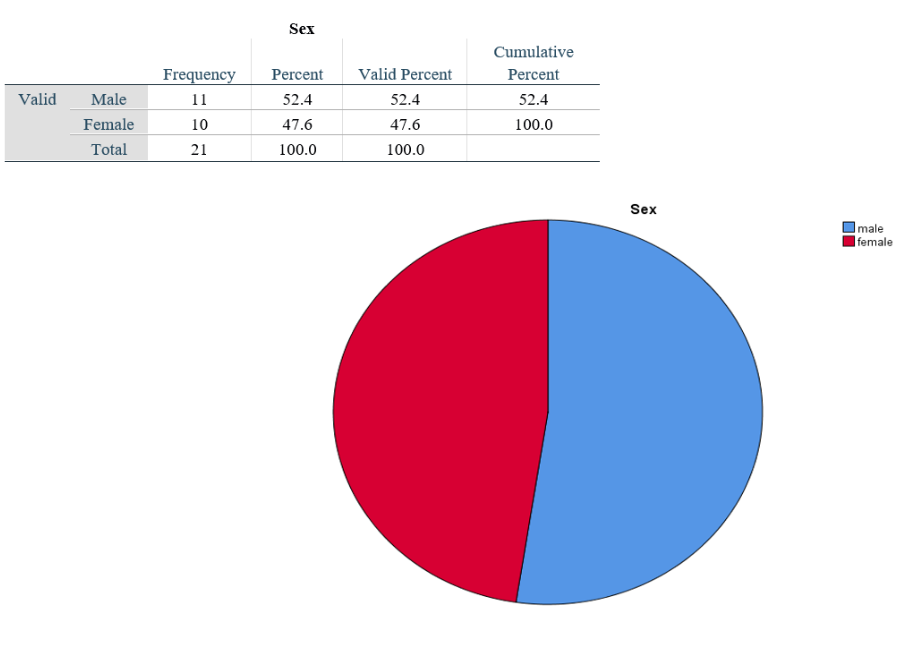

A total of 21 people participated in the quality improvement project. The age of participants ranged from 30 to 60 years with a mean age of 47 and a median age of 49 years. The group included 52.4% males and 47.6% females. Participants identified themselves by race with a composition of 66.7% Black/African American, 19% Caucasian, and 14.3% Hispanic.

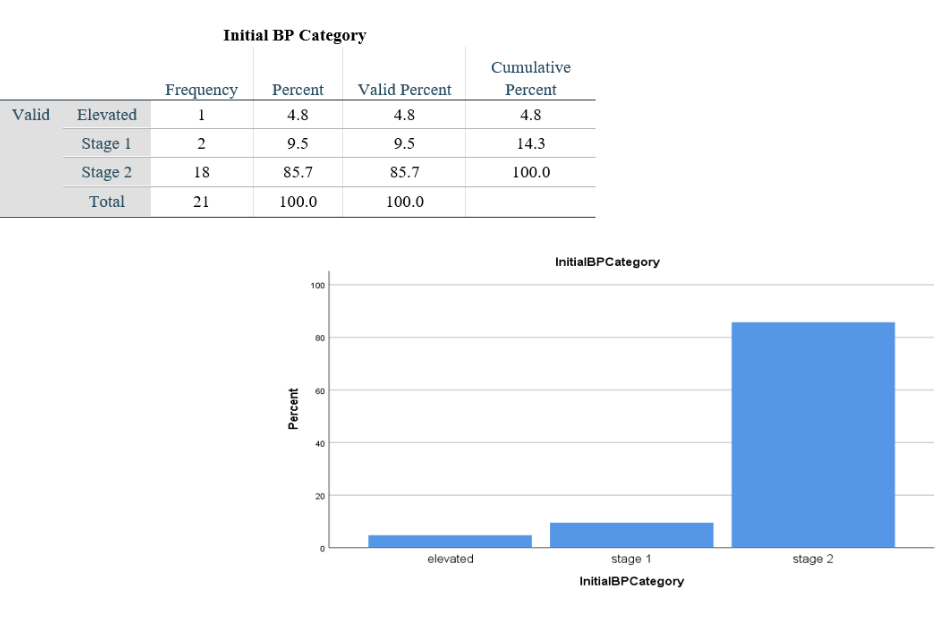

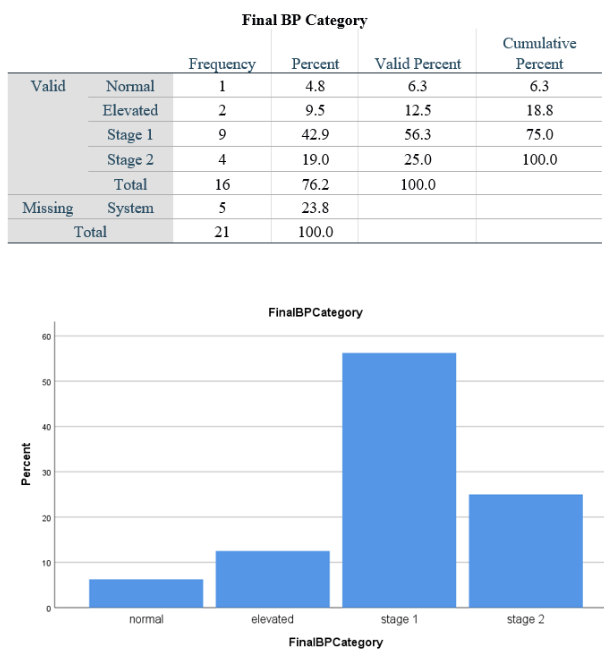

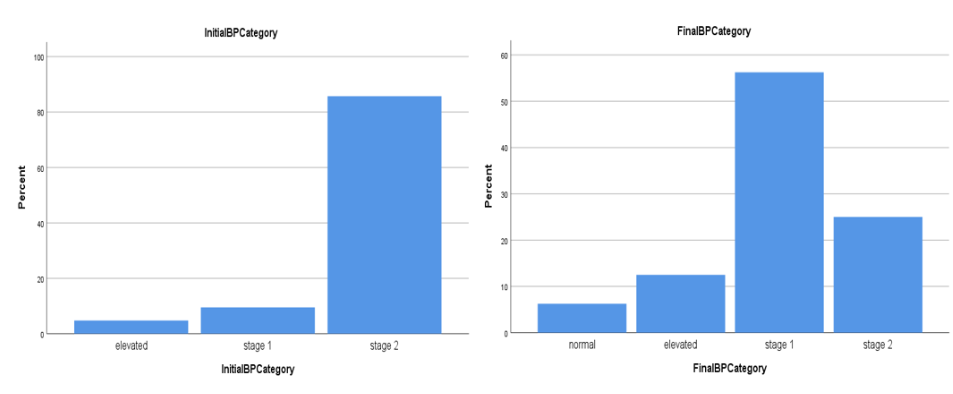

Initial blood pressure readings found that 85.7% of patients had Stage 2 hypertension, 9.5% of patients had Stage 1 hypertension, and 4.8% of patients had elevated blood pressure. Final blood pressure readings revealed improvements showing 25% of patients with Stage 2 hypertension, 56.3% of patients with Stage 1 hypertension, 12.5% with elevated blood pressure, and 6.3% with normal blood pressure.

Most participants had a reduction in average systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more, and 19% of participants had a reduction in average systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure of 0–9 mmHg over the course of the project. Participants who did not follow up after the initial consultation made up 23.8% of the participant group.

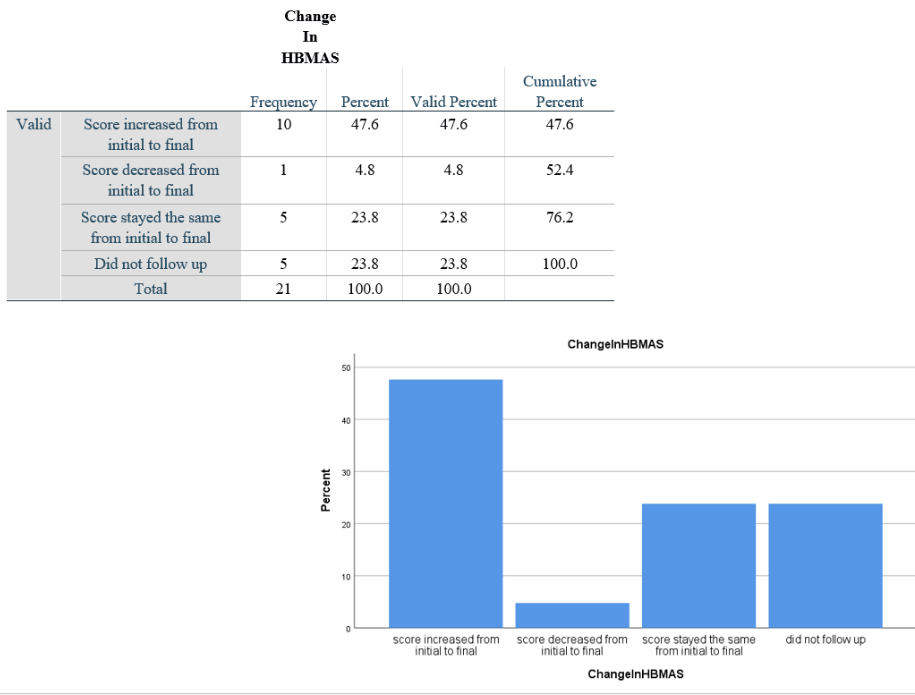

Final scores on the HB-MAS showed 23.8% of participants with the same initial and final score, 47.6% of participants with a higher final score indicating increased medication compliance, 4.8% of participants with a lower final score indicating decreased medication compliance, and 23.8% of participants who did not follow up after the initial consultation.

Limitations

Limitations for this quality improvement project include the small sample size of 21 total participants. Though the demographic composition of the sample size is reflective of the overall population of the project site and the surrounding geographic area, more participants should be included in order to truly generalize the results to a larger population.

Conclusions

Hypertension affects a large percentage of the population and accounts for billions of dollars in healthcare expenditures every year. Reducing the rates of hypertension should in turn reduce the annual economic burden. This QI project aimed to reduce the overall incidence of uncontrolled hypertension and increase the frequency of compliance with prescribed pharmacological therapies. Data analysis revealed that the majority of participants had a reduction in average systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more, with some participants moving into the normal blood pressure category. Final scores on the HB-MAS indicate that medication compliance increased in over half of the participant population. These findings far surpass the goal of reducing the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension and increasing medication compliance by 10% in a given participant group.

SMBP and the HB-MAS are both tools that serve to increase participant awareness of their condition and give them the opportunity to take a more active role in managing their health. The results of the QI project show that by providing targeted education and support, the addition of SMBP was an effective intervention to help reduce rates of uncontrolled hypertension in this participant population.

To improve this project and garner more participant engagement, this author suggests following up with each participant via telephone on a weekly basis for the first four weeks rather than at monthly intervals. This author believes that this may help participants move toward incorporating SMBP as part of their daily routine and may in turn decrease the number of participants that do not follow up after the initial consult.

This project can be easily implemented at other sites by providing the same recruitment, training, and tools to the clinicians and staff at a chosen site. One barrier to implementation at other sites may be the cost of automated upper arm blood pressure devices. If the clinic in question cannot afford to purchase enough devices for each patient to check out, they can purchase a limited number of devices and rotate small cohorts of patients through the project for a total of four weeks rather than 12 weeks. Alternatively, patients can purchase their own automated upper arm blood pressure device and calibrate their machine. This can be done by comparing the readings from the patient’s automated device with that of a manual blood pressure device.

Overall, this QI project confirms that SMBP is an intervention that helps to reduce the incidence of uncontrolled hypertension, and that it can be implemented across a variety of geographic and demographic settings as a way to improve health outcomes for the given population.

Janet M. Pitt, MSN, AGNP-C, is a doctoral nursing student at the University of South Alabama. She is currently employed as an adult-gerontological nurse practitioner at A & M Healthcare Clinic, LLC in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She holds a bachelor’s degree in nursing from the University of Central Oklahoma, a master’s degree in nursing education from Oklahoma Baptist University, and a master’s degree in adult-gerontological primary care from the University of South Alabama.

References

America’s Health Rankings. (2018). Explore high blood pressure in Oklahoma. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Hypertension/state/OK

American Heart Association. (2018). More than 100 million Americans have high blood pressure, AHA says. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2018/05/01/more-than-100-million-americans-have-high-blood-pressure-aha-says

Breaux-Shropshire, T., Judd, E., Vucovich, L. A., Shropshire, T. S., & Singh, S. (2015). Does home blood pressure monitoring improve patient outcomes? A systematic review comparing home and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring on blood pressure control and patient outcomes. Integrated Blood Pressure Control, 8, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.2147/IBPC.S49205

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Hypertension mortality by state. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/hypertension_mortality/hypertension.htm

Fryar, C. D., Ostchega, Y., Hales, C. M., Zhang, G., & Kruszon-Moran, D. (2017). Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015–2016 (NCHS Data Brief No. 289).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db289.htm [CDC 2017b]

George, J. & MacDonald, T. (2015). Home blood pressure monitoring. European Cardiology, 10(2), 95-101. https://doi.org/10.15420/ecr.2015.10.2.95

Jo, S. H., Kim, S. A., Park, K. H., Kim, H. S., Han, S. J., & Park, W. J. (2019). Self-blood pressure monitoring is associated with improved awareness, adherence, and attainment of target blood pressure goals: Prospective observational study of 7751 patients. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 21, 1298-1304. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13647

Kaiser Permanente. (2018). Some racial/ethnic groups have greater chance of developing high blood pressure. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2018-02-racialethnic-groups-greater-chance-high.html

Kim, M. T., Hill, M. N., Bone, L. R., & Levine, D. M. (2000). Development and testing of the Hill-Bone Compliance to High Blood Pressure Therapy Scale. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 15(3), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7117.2000.tb00211.x

Kirkland, E. B., Heincelman, M., Bishu, K. G., Schumann, S. O., Schreiner, A., Axon, R. N., Mauldin, P. D., & Moran, W. P. (2018). Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: National estimates, 2003–2014. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7(11), e008731. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008731

Merai, R., Siegel, C., Rakotz, M., Basch, P., Wright, J., Wong, B., & Thorpe, P. (2016). CDC grand rounds: A public health approach to detect and control hypertension. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(45), 1261–1264. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6545a3

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020a). Healthy people 2030 framework. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/Development-Healthy-People-2030/Framework

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020b). Heart disease and stroke. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/heart-disease-and-stroke/objectives

Qi, L., Qiu, Y., & Zhang, W. (2017). Home blood pressure monitoring is a useful measurement for patients with hypertension: A long-term follow-up study. Biomedical Research, 28(7), 2898–2902. https://www.biomedres.info/biomedical-research/home-blood-pressure-monitoring-is-a-useful-measurement-for-patients-with-hypertension-a-longterm-followup-study.html

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2019). State obesity data. https://stateofchildhoodobesity.org/states/ok/

Target: BP. (2016). Patient-measured BP. https://targetbp.org/patient-measured-bp/

Tulsa Health Department. (2018). Tulsa County health status report. https://insight.livestories.com/s/v2/2018-tulsa-county-health-profile/653fd02d-3706-40f4-aadc-2e8bca6ea7aa/

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2020). Hypertension in adults: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening-2020

Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S., Casey, D. E., Collins, K. J., Himmelfarb, C. D., DePalma, S. M., Gidding, S., Jamerson, K. A., Jones, D. W., MacLaughlin, E. J., Muntner, P., Ovbiagele, B., Smith, S. C., Spencer, C. C., Stafford, R. S., Taler, S. J., Thomas, R. J., Williams, K.A., Williamson, J.D., Wright, J. T. (2018). 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension, 71(6), e13–e115. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065

Appendix A