Pharmaceutical Waste: Is Your Facility at Risk?

September / October 2012

![]()

Pharmaceutical Waste: Is Your Facility at Risk?

Every year United States hospitals and nursing homes generate more than 84,000 tons of hazardous pharmaceutical waste (Sumpter, 2005). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires businesses, including healthcare facilities, to safely manage their hazardous wastes from the moment they are generated to when they are appropriately disposed (RCRA, 1976). States and municipalities also can regulate hazardous waste disposal.

|

Primary Regulatory Bodies that Oversee Pharmaceutical Waste Management • Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

Increasingly, EPA and state inspectors are issuing recommendations and citations to hospitals. A 2011 survey of directors of pharmacy showed that 39% of inspected facilities had received recommendations, and 5% had been cited for their pharmaceutical waste practices (Halvorson, 2011). Not complying with hazardous pharmaceutical waste regulations can result in fines of up to $37,500 per day, per incident (ASHP, 2012). For example, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was fined $51,501 and ordered to spend almost $500,000 to develop a pharmaceutical waste-management program following alleged hazardous waste law violations at two VA hospitals in Kansas (EPA, 2009). A VA hospital in White River Junction, Vermont, was fined $372,254 for improper handling, storage, and disposal of hazardous pharmaceutical waste (EPA, 2005). In a recent survey of 419 pharmacy directors, 74% of respondents had been visited by the EPA or other regulatory bodies governing pharmaceutical waste in the past three years (Halvorson, 2011).

Pharmacists should be accountable for “cradle to grave” management of pharmaceuticals at their facility and may be held personally liable for the disposal of regulated hazardous wastes, but ultimate responsibility lies with a hospital’s chief executive officer (CEO). Senior administrators, pharmacy, pharmacy supportive personnel, nursing leadership, risk managers, environmental services, purchasing, clinicians, hospital legal counsel, and everyone else involved with hospital pharmaceuticals need to know how to limit the generation and properly dispose of pharmaceutical waste.

Regulatory Bodies

Various regulatory bodies are charged with protecting the public from possible harm from exposure to hazardous waste (see below). It is important to note that the complex handling requirements vary at the federal, state, and local levels. The following examples illustrate how their activities can impact hospitals.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

As noted above, the EPA has set the federal mandate for managing listed hazardous chemicals (which include drugs) and the corresponding wastes. However, other regulatory bodies also have regulations that specify the proper management of certain pharmaceutical wastes.

One waste stream regulated by the EPA with which hospitals may not be familiar falls under the Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA) of 1976. This act includes a list of chemicals that have properties of being hazardous, combustible, explosive, or corrosive. Some pharmaceuticals used in hospitals exhibit the characteristics of RCRA-listed chemicals and thus fall under the RCRA regulations and require special handling procedures for pharmaceutical wastes (EPA, 2012).

Department of Transportation (DOT)

In fulfilling the department’s responsibility for ensuring the safe transportation of pharmaceutical waste, federal and regional DOT agents use “reverse tracers.” DOT representatives will stop a truck leaving a facility, pull the manifest, and walk it back to the individual who packaged the waste to make sure that it is going to a proper facility, that the individual packaging the waste understands the requirements, and that they have completed the necessary six-hour training program and understand DOT regulations for properly managing hazardous waste.

Publically Owned Treatment Works (POTW)

A hospital is a place of business and thus held to different standards than the public with regard to POTWs. Pharmaceuticals are engineered to resist breaking down in the harshest of environments, the human body. Even the most advanced water treatment facilities cannot remove all pharmaceutical entities from our water supply. Before putting any chemical, especially a hazardous substance, down the drain, a hospital needs to have documented permission from its local water treatment plants to do that for each of the chemicals involved.

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

DEA regulations say that controlled substances need to be destroyed in a manner “beyond reclamation” (DEA, 2012). However, nothing from the DEA or the states says to put pharmaceutical waste down the drain or into a toilet. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved package inserts for approximately 13 drugs, including fentanyl, tell the public to dispose of unwanted products by using the toilet; however, the FDA never got advisement from the EPA before saying to use the waterway to dispose of products in the public sector. At this time, the EPA, DOT, state environmental agencies, and healthcare facilities are still waiting on statutory changes by the DEA to fully define a process for the proper documentation, collection, storage, transport, and destruction of controlled substances. Until that time, healthcare facilities have very few options, and the sink remains as a waste stream for healthcare facilities to render controlled medications irrecoverable. Ultimately, however, the “legacy” practice of disposing of pharmaceutical waste in toilets or sinks is one that must be eliminated. The proper management of all drugs, especially controlled substances, needs to be thought of with the waste management process in mind.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

Under the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (OSHA, 2012), hospital employees have a legal right to know if they are handling hazards and that their employer has done everything possible to protect them. Since some pharmaceutical wastes exhibit hazardous characteristics, proper education and training with regard to these specific wastes is critical to protect employees while they are working to get pharmaceutical waste off campus.

The Joint Commission (TJC)

TJC has beefed up its Environment of Care standards to include specific standards on the handling of pharmaceutical wastes (ASHE, 2012). When TJC visited Nebraska Methodist Hospital in 2011, they asked to see how pharmaceutical waste was handled. Home Health Agency nurses were asked, “What is your policy? How do you handle fentanyl patches?” Environmental Services was asked to show the DOT manifests for the past year. If a TJC surveyor finds any violations, they have the right to report a hospital to the EPA as being non-compliant with regard to federal or state regulations.

Pharmaceutical Waste Management

The following resources provide detailed information on planning, launching, and implementing a comprehensive pharmaceutical waste management initiative.

Managing Pharmaceutical Waste: A Discussion Guide for Health-System Pharmacists is an excellent tool that addresses minimizing pharmaceutical waste up front. It is available at no cost to Association of Healthy-System Pharmacists (ASHP) members and includes a spreadsheet that can be used to estimate the amount of waste being generated with certain items and the cost associated with that waste (ASHP, 2012).

Managing Pharmaceutical Waste: A 10-Step Blueprint for Healthcare Facilities in the United States is designed to help hospitals develop and implement a comprehensive pharmaceutical hazardous waste management program. This approach combines regulatory compliance and best management practices with waste minimization to safeguard human health and the environment, while minimizing risk in a cost-effective manner (Practice GreenHealth, 2012). Although not an official document, it provides best management practices and guidance based on other facilities’ experiences.

Regional EPA staff also can help you understand pharmaceutical waste regulations and specifically what they are looking for during site visits. Many waste haulers have pharmaceutical-waste consulting arms that are very attuned to the regulations and can help you come into compliance.

Regulated Disposal Methods

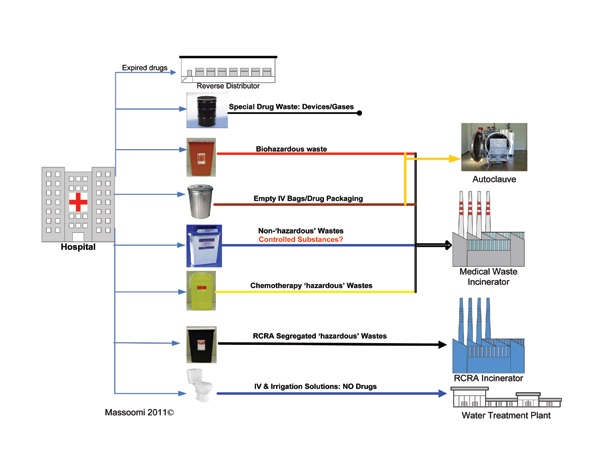

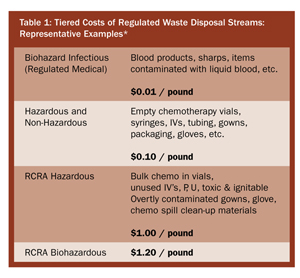

The challenge is to accurately and efficiently identify, classify, sort, and segregate pharmaceutical waste, while providing the necessary documentation to facilitate tracking and regulatory controls (Figure 1, p. 49). Accurate and efficient sorting of waste is financially prudent (Table 1).

Manual Sorting

Manual sorting of regulated waste is possible when the entire inventory has been analyzed and continually updated. Items are labeled during the receiving and/or dispensing processes, and drugs can be “tagged” with the appropriate waste stream. Hospitals with more elaborate computer systems can electronically tag drugs with the proper disposal waste stream for healthcare professionals to reference at the point of disposal. However, manual sorting and documentation of pharmaceutical waste is dangerous, expensive, labor-intensive, error-prone, and allows for potential cross-contamination.

Electronic Sorting

New electronic sorting devices use barcode technology linked to a hospital’s pharmacy information system (PIS) to help identify, sort, and track pharmaceutical waste with minimal human intervention. Scanning a package’s barcoded label automatically classifies the product and opens the appropriate waste container—non-hazardous waste, hazardous waste, biohazardous waste, RCRA hazardous waste, RCRA biohazardous waste, or normal trash—for disposal. Closing the container deposits the waste into a secure bin. The system weighs the waste and generates the required EPA and DOT manifests. Special sensors in the device automatically notify the environmental services department when the waste bin needs to be replaced.

Centralized Segregation

In this approach, all pharmaceutical waste is collected in hazardous waste containers, which are taken to a central area where the mixed waste is sorted by the hazardous waste vendor or trained hospital staff. While relatively easy to implement, this approach is falling out of favor because of storage-space issues and concerns with regard to exposed needles, contamination, and other safety risks. As the generator of the waste, the hospital is liable for any harm to contracted employees.

Managing all Pharmaceutical Waste as Hazardous

An approach that is coming into favor is to manage all pharmaceutical waste as hazardous and to place all waste into “regulated RCRA” containers. The containers can be removed from campus safely and easily, with no need to educate hospital staff on proper disposal. The significant drawback to this approach is that disposal costs for “RCRA regulated waste” are greater than for other types of waste.

Education

Educating staff on the importance of properly managing and disposing of hazardous pharmaceutical waste is essential. “Trash rounds” or “trash-tracers” are one approach. Looking in sharps and waste containers in clinical areas and pharmacy to make sure they are being used appropriately can help identify opportunities for education. Requiring risk managers and administrators to receive waste training along with the clinical staff can also help increase rates of compliance for RCRA-regulated waste.

Future Pharmaceutical Waste Considerations

As the field of medicine continues to evolve and new ways of administering pharmaceuticals to patients arise, new waste stream considerations also arise. In the past few years we have seen a proliferation in new devices that deliver medications, from implantable pumps and pens to the use of nanotechnology. Current disposal regulations do not formally address these newer methodologies. Healthcare facilities need to proactively take the lead in establishing waste streams that are safe for the communities they serve for both existing and future technologies.

Conclusion

Just as the CEO, senior administration, risk management, and clinical staff are responsible for ensuring that patients receive safe and effective medical treatment, they must also ensure safe and proper management and disposal of pharmaceutical waste. Acquiring the expertise and technologies necessary to properly manage and dispose of pharmaceutical waste can help protect your organization’s financial health, your employees, and our environment.

Fred Massoomi is pharmacy operations coordinator at Nebraska Methodist Hospital in Omaha, Nebraska. He may be contacted at fred.massoomi@nmhs.org.

References