Online Patient Networks: How Online Patient – Networks Can Enhance Quality and Reduce Errors

October / December 2004

Online Patient Networks

How Online Patient – Networks Can Enhance Quality and Reduce Errors

![]()

The late Eva Salber, MD, a pioneer of community-based healthcare, noted in 1981 that people with medical problems consult other resources before approaching professionals and that the majority of illnesses are never brought to a health professional at all. Those resources include expert patients, community “healers,” and others who make up a network of highly motivated individuals with an interest in health. Yet, trained in the contemporary climate of provider-as-expert, it is a challenge for even the humblest health professionals to respect and work with their patients’ community-based social networks. These networks, and the fact that most patients do not solely rely on their doctor for care, can feel threatening. But if providers can transcend the feelings of concern or annoyance, and take the trouble to understand how these remarkable communities organize and function, they can transform and improve care.

Informal caregivers pervade human history. In every community, laypeople exist to whom others naturally turn for advice, support, and counsel. In recent American history, medical agencies trying to reach underserved communities have leveraged the status of these natural helpers by identifying them and training them as lay health advisors (LHAs). These volunteers act as liaisons between healthcare professionals and the community (Salber, 1979; Leutz, 1976). They advise on promotive health practice, prevention of disease, early recognition of illness, and simple first aid measures. They may provide specific interventions like encouraging participation in breast cancer screening (Earp & Flax, 1999; Earp, Viadro, & Vincus 1997) or substance abuse referrals (Leutz, 1976). They can be grocers, housewives, ministers, or root doctors, young or old, and the only common characteristics of these natural helpers are empathy, a willingness to listen, and a readiness to help through their extensive social network and community influence at their disposal (Salber, 1979; Leutz, 1976). Thus, the natural helpers trained as lay health advisors can extend the patient-centered network or community to include the medical community and provide a solid bridge between the two (Earp, Viadro, & Vincus, 1997).

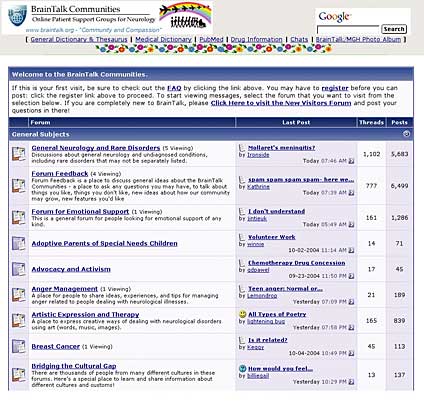

Advances in communication technology have helped bridge the gap between community-based patient care networks and medical-professional based networks more effectively than ever before. The Internet and wireless phones have pushed the boundaries of “community” far beyond physical proximity. Within seconds, whether at home or on the road, one can be in contact with dozens, hundreds, or perhaps thousands of people with similar interests. For example, the Brain Talk neurology Web forum managed by one of the authors (John Lester) attracts tens of thousands of individuals each day. These people are patients and caregivers who use Brain Talk to freely collate and disseminate impressive amounts of disease-specific information and experience to share with other people in similar circumstances. With a few exceptions, laypeople populate Brain Talk and similar sites. Physicians are rarely excluded, but are seldom active in these networks (Norris, Hoch, & Lester, 1998). However, the groups frequently contain self-trained “expert patients” (Ferguson, 2002), individuals with accumulated knowledge about their illness who are invaluable to other patients searching for health information (Ferguson, 2000; LaCoursiere, 2001). These natural helpers are usually informally self-trained LHAs, but reach levels of sophistication that transcend any formal LHA programs (Ferguson & Frydman, 2004).

Strength in Community

Does the burgeoning, Internet-related development of increasing numbers of expert patients/LHAs result in improved efficiency and quality of care? A partial answer comes from the United Kingdom. Unfortunately, the expert patient program instituted by the National Health Service in the UK (Department of Health, 2001) has drawn variable reactions from clinicians. Primary care trusts tend to give it a low priority (Shaw & Baker, 2004; Kennedy, Getely, & Rogers, 2004). Designed to empower the chronically ill, the projects require staffing, monitoring, and promoting, all of which consume precious resources. This top-down approach to the program is disheartening since there is so much to learn from observing how health information is naturally transferred among patients using the Internet and other communication tools. We have observed that these very highly motivated individuals who gather tremendous resources and disseminate it to others could efficiently form the nidus of the NHS program. The strength of the system is in the community — not everyone knows as much as the “experts,” but they learn how to access these expert members, who in turn know how to access the information.

These communities also generate important information, even scientific data. Many previously unexplained medical phenomena were first noticed by patients. For example, the sexual effects of Viagra (sildenafil) were originally discovered by patients. Originally explored as an anti-angina drug, the effects on sexual function were discovered when patients took the researchers aside and told them about this side effect. Connecting patients to each other and to their physicians through the Internet has expanded this role, and in some cases, eliminated the “physician researcher” middleman in the process.

The Life Raft Group

Although most online groups are open to everyone, a group of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) has formed the Life Raft Group, which only patients and their family caregivers can join (www.liferaftgroup.org). They scrutinize potential members carefully, making sure they actually have this disease and understand that they will be expected to share their medical experiences. The Life Raft Group operates as a highly organized, networked scientific work group that excludes even the top GIST specialists and the researchers who conduct the clinical trials in which many members are enrolled. The group has its own medical librarian who compiles regular medical updates from each member, a membership director, an editor, a professional newsletter producer, a Web master, a treasurer, a list manager, a government relations coordinator, and a “Science Team” comprised of approximately 10 highly committed members who regularly review the medical literature, speak with leading GIST specialists, interact with top medical researchers, keep up-to-date on the latest drug company information, and check in with other support groups in an ongoing attempt to understand the current state-of-the-art GIST therapy.

One advantage of patient-initiated research is speed. Recruitment and dissemination of findings to patients are particularly fast, since the “subjects” and people impacted by the findings are performing the study. In June 2001, the Life Raft Group published its first study, which was about the effectiveness of a drug called Gleevec, through its newsletter. In October 2001, the group published its first comprehensive study of Gleevec side effects. In addition to collecting the usual data, the study broke new ground in several areas: It provided data on the quality of the clinical care available to study participants at each of the centers conducting clinical trials, attempted to evaluate the information sources patients relied upon, developed a methodology by which patients could, in effect, serve as their own control group, and introduced a new scale for rating the severity of side effects from the patient’s point of view.

These online community networks do not replace traditional research channels or the healthcare process, including doctors visits, but they do augment it and improve it by leveraging the organizational, analytic, and communicative ability of a few to inform, support, and guide many. Although online patient networks are run by patients for patients, we think that if providers are integrated into these networks, quality can be improved and errors reduced. Healthcare professionals can seed the communities with quality scientific information, which will augment the experiences being shared. Fear of layperson-produced errors and mistakes appears to be unfounded. We have found that online health communities are largely self-policing with regard to misinformation (Hoch, Norris, Lester, & Marcus, 1999), and collective filtering through the community provides checks and balances that cannot occur in a one-on-one encounter.

Providers who are interested in fostering this environment for their patients can create spaces, provide resources, and help in many ways. However, most important, they should not force a hidden agenda upon the community (Lester, Prady, Finegan, & Hoch 2004). Healthcare providers might think about working online with their own patients. One example is the PatientWeb system for patients with epilepsy at the Massachusetts General Hospital (www.patientweb.net). Online collaboration can include virtual journal clubs where doctors and patients can keep each other abreast of the literature, shared experience forums where all members (doctors and patients alike) have an opportunity to understand each other’s struggles, and private message boards where individuals can leave confidential messages about medical problems for each other.

The Role of Technology

Looking forward, it is important to remember the critical role of innovative communication technology in the formation and evolution of these patient-based social networks. Technologies such as email, instant messaging, and Web-based bulletin boards are inherently democratizing, providing individuals with previously unheard of powers of interpersonal communication (e.g., 24/7 accessibility and the ability to transfer documents globally). The complexity and power of current patient-based social networks is directly based on the accessibility of these new communication technologies. As consumer information technology advances in the future, it will be critical to monitor the introduction of completely new communication technologies to see how patient-based social networks embrace and use them to extend their communities. Undoubtedly, the patients will be the pioneers in using these new tools, and we will have much to learn by simply observing their progress.

References

Department of Health. (2001). The expert patient: A new approach to chronic disease management in the 21st century. London: Stationary Office.

Earp, J. A., & Flax, V. L. (1999). What lay health advisors do: An evaluation of advisors’ activities. Cancer Practice, 7(1), 16-21.

Earp, J. A., Viadro, C. I., Vincus, A. A., et al. (1997). Lay health advisors: A strategy for getting the word out about breast cancer. Health Education & Behavior, 24(4), 432-451.

Ferguson, T. (2000). Online patient-helpers and physicians working together: A new partnership for high quality health care. British Medical Journal, 321(7269), 1129-1132.

Ferguson, T., & Frydman, G. (2004). The first generation of e-patients. British Medical Journal, 328(7449), 1148-1149.

Ferguson, T. (2002). From patients to end users: Quality of online patient networks needs more attention than quality of online health information. [Editorial]. British Medical Journal, 324(7337), 555-556.

Hoch, D., Norris, D., Lester, J., & Marcus, A. D. (1999). Information exchange in an epilepsy forum on the World Wide Web. Seizure, 8(1), 30-34.

Kennedy, A., Getely, C., Rogers, A., & EPP Evaluation Team. (2004). National evaluation of expert patients programme: assessing the process of embedding EPP in the NHS: Preliminary survey of PCT pilot sites. Manchester, England: National Primary Care Research and Development Center. Retrieved July 15, 2004, from www.nprrdc.man.ak.uk/PublicationDetail.cfm?ID=105

LaCoursiere, S.P.(2001). A Theory of Online Social Support. Advances in Nursing Science, 24(1), 60-77.

Lester, J., Prady, S., Finegan, Y., & Hoch, D. (2004). Learning from e-patients at Massachusetts General Hospital. British Medical Journal, 328 (7449), 1188-1190.

Leutz, W. N. (1976). The informal community caregiver: a link between the health care system and local residents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 46(4), 678-688.

Norris, D., Hoch D., & Lester, J. (1998). An Internet forum for epilepsy support: A survey of users. Clinical Neurophysiology, 39(Suppl. 6), 229.

Salber, E. J. (1979). The lay advisor as a community health resource. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 3(4), 469-478.

Salber, E. J. (1981). Where does primary care begin? The health facilitator as a central figure in primary care. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences, 17(2-3), 100-111.

Shaw, J. & Baker, M. (2004). “Expert patient”—Dream or nightmare? British Medical Journal, 328(7442), 723-724.

Vogel, E., Prady, S., Lester, J., & Hoch, D. B. Unpublished Data.

John Lester is the information systems director for the department of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital, a research associate at Harvard Medical School, and co-director of the Harvard Interfaculty Neuroscience Program. Lester has created and studied the growth of online communities involving patient self-help groups and medical education collaborative environments, as well as developing online communities that allow patients and their physicians to communicate. He may be contacted at braintalk@gmail.com.

Stephanie Prady and Yolanda Finegan are both with the Neurology Information Systems Research and Development Group at Massachusetts General Hospital. Prady is project manager, and Finegan is a research assistant.

Daniel Hoch is assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and practices in the department of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital, with subspecialty expertise in epilepsy. With John Lester, Stephanie Prady, Yolanda Finegan, and others at Mass. General, Hoch has worked extensively with large and small groups of patients who have been “enabled” by modern communication technology.

- Proceedings from the Quality Colloquium at Harvard University:

- • Introduction

- • Patient Safety: Ethical Considerations in Policy Development

- • P4P Contracting: Bold Leaps or Baby Steps?