MITSS: Supporting Patients and Families for More than a Decade

May/June 2013

MITSS: Supporting Patients and Families for More than a Decade

Over the past decade, the patient safety movement has focused much of its attention on prevention, and rightly so. Still, even in the safest of systems, things can, and often do, go wrong. Of late, much has been published regarding the “second victim,” a term used to describe healthcare providers finding themselves on the sharp end of an error or adverse event. Yet, little has been documented about the emotional impact on patients and their families and the need for support following these events.

Over the past decade, the patient safety movement has focused much of its attention on prevention, and rightly so. Still, even in the safest of systems, things can, and often do, go wrong. Of late, much has been published regarding the “second victim,” a term used to describe healthcare providers finding themselves on the sharp end of an error or adverse event. Yet, little has been documented about the emotional impact on patients and their families and the need for support following these events.

This article chronicles the adverse event that catalyzed the formation of Medically Induced Trauma Support Services (MITSS), a non-profit organization with a focus on emotional support in the aftermath of adverse events; the evolution of the organization over the past 11 years; and the development of a menu of support services. By providing a detailed discussion of common themes, shared emotions, long-term consequences, and effective interventions, we hope to inform a greater understanding of the patient/family experience when things go wrong in healthcare.

Background

In 1999, Linda Kenney, a 37-year-old mother of three, was admitted to the hospital for her 20th surgery—she had been born with bilateral club feet. When a nerve block was inadvertently administered into her circulatory system, she went into cardiac arrest, necessitating open heart massage and bypass to save her life. She awoke days later with tubes coming from her chest, unaware of what had transpired. The only conversation she had with the medical staff regarding her event was with a physician who told her that she had an allergic reaction to the local anesthetic, bupivacaine. She intuitively knew, though, that this was not the case.

To her surprise, 10 days after discharge, Linda received a letter from the anesthesiologist, Dr. Rick van Pelt. He made himself available, whenever she was ready, to talk about what had gone wrong. Linda and Rick published their story in Patient Safety & Quality Healthcare in 2005.

Over the next six months, as friends and family began to move on with their lives, Linda became increasingly emotional. Unable to shake her need to connect with others who had been through similar experiences, Linda contacted the hospital where her event occurred and discovered no such services were offered. She turned to the Internet and again could not find anyone dealing with the issue head on—no less offering support.

Linda felt compelled to change the system that had failed her, her family, and the clinicians involved in her care, so she founded MITSS—an organization dedicated to providing emotional support for patients, families, and clinicians who experience adverse medical events and medical errors. Dr. van Pelt became one of the founding members of the MITSS Board of Directors and would later serve as our first Board Chair. I have served MITSS as communications director since 2003.

After the organization was incorporated in June 2002, we put together a brochure for patients and families. Included in that first brochure was MITSS’s definition of “medically induced trauma”:

An unexpected complication due to a medical/surgical procedure, medical/systems error, and other medical circumstances that affect the overall wellbeing of an individual and/or family member(s).

Linda envisioned that hospitals would welcome the assistance and distribute the information freely to their patients. She delivered a large number of brochures to the hospital where her event occurred, but, needless to say, the information didn’t get much traction. In retrospect, Linda realizes the risk manager wasn’t sure what to think about this new organization and was wary of Linda’s motives. That was back in 2002, when open disclosure and apology policies were not routinely in place nor adhered to. The subject of medical errors, unanticipated outcomes, and their impact on patients and families was, and remains to this day, awkward and emotionally charged.

Unbeknownst to Linda, the same year her event occurred, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the landmark report, To Err Is Human (2000). That sobering document revealed that nearly 98,000 patients die annually in U.S. hospitals from preventable medical errors. While Linda felt unique and alone, she would soon discover that she and her family were merely a few of the millions of people impacted by adverse events annually. She would also learn that her simple idea of providing support to those suffering emotional distress due to medical errors and adverse events would come up against entrenched cultural barriers.

Support for Clinicians

The focus of this article is to discuss MITSS’s patient and family support—its history and evolution, current service offerings, data, and learning, as well as plans for the future. It should be underscored, however, that from the outset the MITSS mission of Supporting Healing and Restoring Hope has included clinicians. Linda Kenney witnessed firsthand the emotional impact her event had on the clinicians involved her care—the orthopedic surgeon, members of the code team, and, especially, the anesthesiologist, Dr. van Pelt. Being struck by the depth of pain “on the other side” as well as the non-existence of support services available for clinicians, she knew MITSS would need to address the issue with a more holistic approach. Rather than individual support, our efforts to support clinicians have focused on helping organizations develop their own programs. For more information, see the MITSS Clinician Support Tool Kit at http://www.mitsstools.org/tool-kit-for-staff-support-for-healthcare-organizations.html.

Support for Patients and Families

In the beginning, MITSS sought clinical guidance for developing a patient and family support program. Under the direction of a mental health practitioner specializing in trauma, the first MITSS group for patients and families was held in spring 2003.

It was not known in 2003 what other types of support would most benefit patients and families who contacted MITSS. Callers were looking for everything from a sympathetic ear to assistance navigating the complexities of the healthcare system. Their sense of isolation and desire for connection were palpable. Anger, depression, grief, anxiety, fear of re-engaging with the healthcare system, and difficulty dealing with family and friends after their event were among the feelings and emotions they experienced.

We also heard many reports of people who experience a delay in the full emotional impact from an adverse event—most often, 3 to 6 months post-event. This is somewhat understandable given that patients may not be ready to deal with their emotions right away. They may be focused on their physical recovery. Family members may also be focused on their loved one getting better and may not be able to deal with their emotions until a later time. In the worst-case scenario, that of a death, family members may be grieving, and it is not until later that the negative feelings about what happened may surface (Kenney, LaFarge & van Pelt, 2009).

Gathering Momentum and Dealing with Challenges

As the MITSS story gained national exposure (largely through a keynote speech Linda Kenney and Rick van Pelt gave at the National Patient Safety Foundation [NPSF] Congress in Boston in 2004 and mainstream media coverage), requests for assistance and support markedly increased. To respond effectively to the needs of these patients and families, MITSS staff and members of its Board of Directors underwent intensive training in “first responder” techniques: emotional first aid, active listening skills, handling “difficult” callers, and recognizing and dealing with suicidal callers.

In 2004, Susan LaFarge, PsyD, a licensed clinical psychologist and member of the Board of Directors, joined the staff to provide expertise and guidance over the clinical aspects of the organization as well as to oversee and facilitate the groups. Dr. LaFarge was struck by the lack of research study in this area, with the exception of the notable work of Charles Vincent and John Church, who found “the levels of distress [from ‘medical accidents’] are similar to those of people who have experienced recent serious life events (such as bereavements and natural disasters)” (Church & Vincent, 1996). Vincent followed up in 2003, advocating for greater understanding of the emotional impact in the hope of developing effective interventions. Other than Vincent’s work, however, there was little else to be found in the literature on the emotional impact on patients.

MITSS also partnered with a local university, the Massachusetts School of Professional Psychology, to bring in doctoral and masters-level students to assist in the support functions of the organization and to help with ongoing research. We embarked on our own research project, conducting an online survey (linked to the MITSS website) in an effort to capture data around the patient and family experience following an adverse event. (Discussion of some of the findings from that survey appears in an upcoming section.)

One of MITSS’s early challenges was to help people living outside of Massachusetts. The demand was there (in fact, a large percentage of the callers were from out of state), but there were few other organizations offering patient and family support. Additionally, MITSS’s emotional support services were never meant to replace the work of a private therapist. Depending on the severity of the trauma, many clients who contacted the organization were encouraged to either continue working with their own therapist or to engage one. Thus, we were charged with the task of developing a list of resources—external navigational assistance as well as clinical referrals to counselors and therapists who specialize in trauma.

MITSS has developed close relationships with many patient safety advocates and their organizations primarily through extensive travel across the country for speaking engagements; involvement with local, national, and international patient safety initiatives; and, participation in the patient safety and quality movement. These contacts have proven to be valuable resources, especially when connecting callers to peers whose circumstances are similar to their own; e.g., someone who has lost a child or a patient dealing with chronic pain due to an error. In recent years, further fueled by social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter, a more expansive support network has emerged.

Role of Disclosure and Apology

Lack of transparency, timely communication, and sincere apology have proven to be significant barriers for many patients seeking to recover emotionally after an adverse event. It has been well documented that the opportunity for genuine apology and full disclosure opens up the possibility of emotional healing and forgiveness (Hurwitz & Sheikh, 2009; Allan & McKillop, 2010; Berlinger, 2005; Leape, 2006; Moskop, Geiderman, Hobgood & Larkin, 2006). Leape (2006) further deemed apology a “therapeutic necessity,” as it allows forgiveness and the preservation of the patient-provider relationship (Allan & McKillop, 2010; Berlinger, 2005; Leape, 2006; Cohen, 2010; Vincent 2003). This is certainly in concordance with what MITSS has heard anecdotally from patients and families.

Strategically, we recognized the need to get involved in the larger discussion regarding disclosure and apology by partnering with progressive organizations (e.g., IHI, CRICO, NPSF, Health Care for All, the Mass. Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital) moving this agenda forward. The thinking is simple: If healthcare wouldn’t acknowledge that these events occur, how could we ever get to a deeper understanding of the emotional impact they inflict and develop effective interventions?

Menu of Services

Drawn from our experience with hundreds of callers, in-person interviews, and data captured online, our current menu of support services for patients and their families includes:

- One phone call or meeting—Someone to listen, reassure, and validate.

- One or more phone calls—May entail referral to various resources, and the client may wish to “check back in” with a MITSS staff person.

- Referral to someone who has had a similar experience and who can empathize, support, and help to problem solve.

- Counseling—Brief, problem-focused counseling with a clinical staff member is offered (in person or on the telephone) when a group setting is not the best therapeutic approach or accessible to the patient/family member.

- Group counseling—A 10-week therapeutic, educational support group for patients and families.

The level of intervention that a patient or family member receives is determined on a case-by-case basis and is influenced by a number of factors including, but not limited to, personal preferences, geographic location, and appropriateness for a support group.

Therapeutic Educational Support Group

The MITSS Therapeutic Educational Support Group is our most intensive intervention. Patients learn about concrete concepts related to trauma (what it looks like, how it is affecting them now, and how it can impact them in the future), and related handouts are given at each meeting. While emotional support is initially provided by the facilitators, the group eventually begins to function as a peer support group.

The group curriculum consists of 10 modules, which are listed below. The facilitators may choose to change the sequencing of the modules in order to better address the needs of the individual group members.

- Introduction

- Trauma & Trauma Response

- Guilt & Shame Issues

- Dealing with Family & Friends

- Storytelling

- Grief & Loss Issues

- Dealing with the Medical Profession

- Meaning-making

- The Healing Process & Self-Care

- Wrap up & Termination

A more detailed explanation of the weekly modules is available on the MITSS website (http://www.mitsstools.org/uploads/3/7/7/6/3776466/mitss_educational_support_group_2012.pdf).

A survey is administered at the first and last group session. Facilitators are looking for reduction in symptoms and any comments offered by participants that may provide further insights into the patient/family experience. Continuous improvement, incorporating patient/family feedback, is built into the process. Surveys have also been sent out to participants six months following group experience to gauge how they are faring in the longer term.

In general, after completion of the 10-week group, participants have reported feeling:

- less anxious and depressed;

- less isolated, as they have connected with people who truly understand what they are going through;

- better equipped to deal with the medical profession, as well as friends and family, going forward; and,

- more knowledgeable about trauma and how to handle its effects with helpful tools and strategies.

Here are just a few of the responses that we gathered from patients and families we asked to comment after completing the group:

Progress is slow but steady. The group made me feel I had tools to cope and use. I use them each day.

The MITSS support group was a gift. It afforded me an opportunity to share with others who have experienced medically induced trauma my pain in a safe, respectful environment. It helped me learn, grow and move forward. I am very grateful for the opportunity and ongoing support.

I’ve learned to really care for my own needs and find joy where I can. I don’t take myself too seriously anymore—life is just too short. Though I’ll always be floating in the river of grief, I’m not drowning in it anymore.

Online Survey

Due to the scarcity of research on the topic, and in order to capture data on this underserved and understudied population, Susan LaFarge, PsyD, and Erin O’Donnell, PsyD, developed an online survey in October 2006. The questionnaire is linked to the MITSS website. As of April 2013, 293 people have started the survey, and 219 have completed it. The survey questions cover demographic information, information about the “event” (e.g., surgical/medication/other, whether there was an explanation given, whether an apology was offered, whether or support services were offered), and questions to gauge the short- and long-term emotional impact.

In this article, we will not provide an in-depth analysis our survey data. Rather, what follows is a brief “report out” on some of the findings that we found particularly noteworthy, as well as those that reflect familiar themes.

To date, respondents have come from 40 states and 7 countries. They are primarily female (94.5%) (n=292), and their ages range from teens to 80s. The majority of respondents include females in their 40s (31%) and 50s (33%). Most participants are patients (64%), with 21% of reporters being family members.

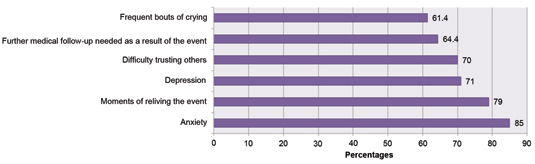

Survey participants were asked to report on 20 criteria related to anxiety, depression, PTSD symptoms, and their medical condition following the event. The top six responses (n=236) are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Top 6 Self-Reported Experiences Following Adverse Events

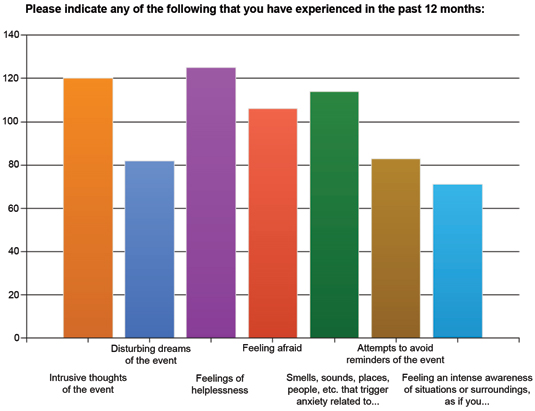

Figure 2 shows responses (n=162) to a question about symptoms experienced over the past 12 months, related to trauma.

Figure 2. Symptoms Related to Trauma

This is especially noteworthy given the majority of participants had significant time lapses between their events and completing the survey (>68% had more than 2 years since their event and 31% had 6 or more years):

- 1 year ago or less 31%

- 2-5 years ago 37%

- 6-10 years ago 16%

- >10 years ago 15%

- N=221

Overall, survey responses indicate that patients and families can experience enormous distress around adverse events: anxiety, depression, fear, feelings of helplessness, intrusive thoughts of the event, mistrust, and variety of physical symptoms related to depression and anxiety. As noted, these difficulties may be longstanding in nature.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Tremendous efforts are being waged to avert medical errors and adverse events, but harm from medical care is still commonplace. As one patient so aptly put it:

I realized that there is no protection—no safety net. This can happen to anyone.

The circumstances of each case are unique. The range of trauma experiences fills an entire spectrum, but common themes have emerged, including anxiety, depression, fear, and anger, to name a few. In many cases, the full emotional impact may not be totally realized until months following the event. There is further evidence that these difficulties can be longstanding and, in some instances, life altering.

While many hospitals and healthcare systems are embarking on a commitment to timely disclosure, sincere apology, and more transparent communication, a deeper understanding of the patient experience is indeed called for. Given the changing culture, the time may be ripe for organizations to re-evaluate the way they support their patients and families following adverse medical events.

For its part, MITSS will:

- continue to provide support;

- share what we learn from the patient and family experience; and,

- develop a tool kit for healthcare to better serve patients and families impacted by adverse events.

Winnie Tobin is communications director of MITSS and may be contacted at wtobin@mitss.org.

References