Medication Safety Recognition Program Designed to Improve Employee Engagement

By Stephanie D. Yarbrough-Morgan, PharmD, BCPS, and Elizabeth A. Wade, PharmD, BCPS, FASHP

Concord (New Hampshire) Hospital began its medication safety recognition program, which was introduced in 2016 and then revised in 2017, in the pharmacy department with the goals of improving the quality of medication errors reported, increasing the number of individuals who consistently reported medication errors, and increasing employee engagement. This program was designed to foster an environment where staff members reflexively consider safety. In addition, the program aimed to show professionals that analysis of and conversation around errors and failures should be welcomed rather than dreaded. This paper describes one option for encouraging medication error reporting, improving risk perception, and strengthening staff engagement in process improvement for an inpatient pharmacy department.

The first step in creating the medication safety recognition program was to research literature for programs that already existed and could be used as a blueprint. Research into existing programs in healthcare facilities was carried out by internet search. While the search did locate medication safety recognition programs in place, their descriptions did not explain how to set up a program successfully and how to design metrics around it to show support of a strategic plan. The research then focused on finding recommendations for how to roll out a successful recognition program in general and how to gain staff acceptance. The occupational safety and industry arenas yielded quite a bit more published information on these topics, and this information helped to guide the rules of Concord Hospital’s recognition program. Some of the key takeaway items from this research were to: 1) recognize often and consistently 2) be transparent and fair 3) make the recognition personal 4) make the recognition as public as possible (Smith, 2013). The examples given usually recognized an individual, and so the first edition of the medication safety recognition program did the same.

Background

The medication safety team at Concord Hospital comprises a medication safety officer (MSO), a medication safety pharmacist, a provider liaison for medication safety, and a pharmacy IV compliance specialist. While the medication safety program is within the pharmacy cost center, the MSO position is an institutional appointment and reports to the vice president of professional services rather than to the director of pharmacy. The medication safety pharmacist is a part-time position that reports directly to the MSO. This pharmacist assists with investigation of medication error reports (especially those involving the pharmacy department directly), sits on medication safety committees, and fosters and maintains programs and educational opportunities that support the medication safety strategic plan. The provider liaison for medication safety is a part-time position in which a member of the medical staff is hired to assist with investigation of medication error reports, interface with medical staff members regarding safety issues, and serve on committees and work groups as a medication safety representative. The provider liaison does not report directly to the MSO, but does work closely with all members of the medication safety team. The pharmacy IV compliance specialist is the lead IV room technician who has additional responsibilities involving safety, quality, and regulatory compliance. This position works closely with members of the medication safety and pharmacy management teams.

At Concord Hospital, staff voluntarily report events using the central software program iCare®, which is a product of Datix®. The quality department and the MSO initially access each event, and the MSO triages any medication-related event for assignment to one of the medication safety team members or to a specific department leader for further investigation and follow-up. Single individuals lead event investigations as primary investigators and close the investigations when all contributing factors are believed to have been discovered. Committee meetings or work groups then hold discussions on the events for identification of mitigating system or process improvement opportunities. Depending on what the meeting attendees or primary investigators decide, staff then take further action or engage in education.

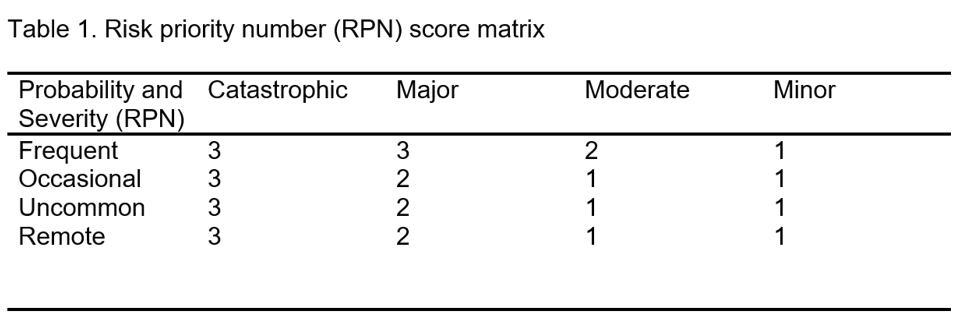

When the MSO triages medication safety event reports, each event receives a risk priority number (RPN) based on its potential for harm (National Patient Safety Foundation, 2015). (See Table 1.) The first component in deciding the risk is potential frequency. For example, if the compounding instructions for a batched parenteral item contain an error, then the error frequency is quite high because the product is made in quantity and 100% of that quantity will contain the error.

The second component is potential harm if the error reaches the patient. It is important to remember that potential harm is just as concerning as actual harm. The error does not need to reach the patient to receive a very high severity scale.

After the investigation concludes, the RPN can be adjusted based on any additional or clarifying information. Note that the RPN is a method for prioritizing investigation and review of events by potential risk, rather than by actual harm.

Pharmacy department medication safety recognition program

The medication safety team, in collaboration with pharmacy management, developed the goals for the recognition program. The most important goals were to:

- Increase participation in the medication error reporting program

- Increase the number of error reports that highlight events that have significant potential for patient/employee/organizational harm and/or happen frequently, with a disruption in workflow

- Improve systems thinking and increase employee engagement

Incorporation of goals into the program. Goal 1 aimed to increase participation in the medication error reporting program. To encourage participation, the program tracked the quantity of event reports reported by each staff member, and each month the highest-reporting pharmacist and technician received recognition in the pharmacy newsletter and a monetary reward. The program implemented this goal with the belief that the number of people in a department who report on a consistent basis is equally important as the number of events consistently reported overall. If a true cross-section of the staff sees the importance of repeated participation in the event reporting process, then the process analysis itself can be more robust. Multiple viewpoints are valuable in finding the root cause of an error.

Midway through 2017, the medication safety team solicited feedback from the pharmacy department regarding satisfaction with and potential improvements for the recognition program. The staff felt that focusing on the quantity of events reported by each person each month was a dissatisfier; they preferred to focus on group success rather than individuals. While the original design did increase the quantity of events reported and the level of employee engagement, it did not increase participation of a cross-section of the staff. Instead, the creation of a competition between individuals only encouraged existing reporters to report more, while those who didn’t report continued to not report. To increase their reporting numbers, some employees began reporting events that had a lower RPN (and therefore were not as valuable) in addition to the events they would have normally reported. Since all medication error reports receive an investigation, this resulted in less value-added time for investigators and decreased the time available to focus on reports with a higher RPN.

The medication safety team ceased the program temporarily for revision. Some months later, the team rereleased the program in its current form, where the department is recognized for meeting goals as a group. This design supports the idea that no single person or small group can create a safe environment for patients; instead, a safe environment takes everyone understanding and working toward improved processes. The “2.0” revision of the program now reports and measures the accomplishments of the department as a whole rather than individuals. It keeps the names of reporters confidential and does not differentiate between pharmacist and technician.

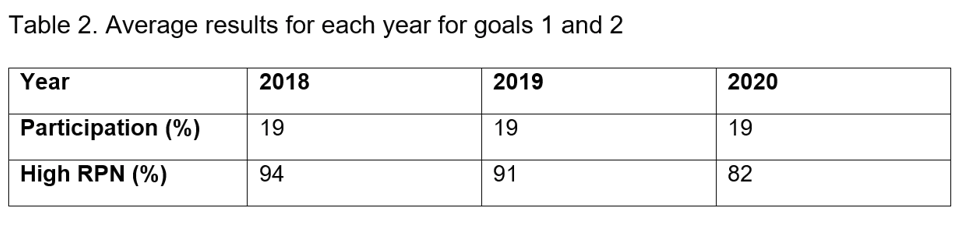

The program awards one point to a department for each person who submits one or more event reports in a given month. Then each month, the program calculates the percentage participation of each department based on the number of points divided by the department’s total number of employees. Each quarter, the program averages the results from each month, and if the average reaches 25%, the department receives congratulations and a reward—normally food. By focusing on whether an individual participates, not how many times in a month an individual participates, the program encourages participation while reinforcing the concept that all viewpoints are critical to medication error investigation. Through this, we noticed an increase in events reported by pharmacy technicians as well, since pharmacy team members would encourage each other to enter the reports.

The second goal of the recognition program was to increase the quality of events reported. To do this, the staff received education about RPNs, which could then be used as a measure for goal 2.

The program counted events in the upper two-thirds of the severity scale as meeting the goal of reporting events with more significant potential for harm. By choosing this goal as a focus, the medication safety team could educate the staff about the dangers of outcome bias and reinforce that concept over time. Outcome bias arises from the mistaken belief that processes, practices, and systems are not flawed unless an error actually reaches a patient. Individuals falsely assume that because an event has not caused harm in the past, there is no value in analyzing the processes in question to look for opportunities for improvement. When outcome bias influences a culture, there is usually very little attention given to investigation or analysis of an error that did not reach a patient, or anticipating future errors that could reach a patient. In other words, the culture is reactive rather than proactive. In addition, using the RPN allowed the medication safety team to teach the pharmacy staff to focus on system errors with high potential for future harm, rather than errors that are less likely to be repeated.

Goal 3 aimed to improve systems thinking and increase employee engagement. For this goal, the medication safety team and pharmacy management agreed to recognize all instances of frontline staff’s engagement in improving medication use processes. This underscores the message that safety is integral to better patient care. Each quarter, the medication safety pharmacist meets with the MSO and all members of pharmacy leadership to identify individuals who have been involved in a process improvement project where they went above and beyond their job descriptions. They enter each name into a drawing, with a separate entry for each project. The team draws three names each year and awards three separate prizes. The first is a monetary reward, the second is one pre-approved pharmacy-related education day, and the third is special early consideration for one day of earned paid time off. Staff must use the two latter prizes in the 12 months immediately following the drawing.

The second aspect of recognition for meeting the engagement goal is giving each involved person a handwritten thank-you note signed by all members of the pharmacy administration and medication safety team. These notes are delivered in person. Anecdotally, the notes have seemed more important to the staff than money or time off. When receiving these notes, most staff members seem genuinely touched. Each card contains reasons for appreciation that are specific to the staff member and name their accomplishments. In addition, the staff member is not asked to pick up the card from an office—the team delivers the card directly to the staff member. More than once a staff member has responded with appreciation such as “This really means a lot to me,” “This is so kind of you,” or “I really needed this.” In an age where we use technology to communicate in nearly every setting, the personal touch of a handwritten note is still important.

Rollout and maintenance. In our current event reporting process, the MSO triages all medication-related event reports and delegates them for investigation. The MSO tracks all the error reports submitted by the pharmacy department and tallies how many of the staff submit reports in a given month. This was initially a manual process, due to voluntary reporting and being unable to reliably query the reporter information fields in the iCare system, but has since become more automated. The team dedicated a great deal of time and energy to excitedly and enthusiastically present the program to pharmacy staff.

The mission was to make the program transparent, fair, and fun. Talking about errors and places where processes fail can be disheartening. A well-designed recognition program can not only educate staff, but also help to turn error reporting into a positive experience. Meeting a goal is cause for celebration and is treated as such.

The program schedules celebrations for both the day shift and the evening and night shift on a day when the most people are working. Staff members have enjoyed offerings like yogurt parfait bars, ice cream bars, whoopie pie platters, smoothies from a local business, nacho bars, and many more. During the third quarter of 2020, the pharmacy department met both goal 1 and goal 2. For this event, the program held an extra-special celebration, with food and a drawing for a $25 gift card. The medication safety team aims to spark lots of conversation around the recognition program, and so each month the team sends an article to the pharmacy staff that reports the percentages for the goals. That article also has content designed to be encouraging, appreciative, and educational. The recognition articles have served as encouragement and gratitude for staff through the COVID-19 pandemic, as education, and as effusive praise when departments reach goals. The recognition program’s second version has been in place since October 2017. In that time, the participation has remained steady at 19% even through the pandemic, demonstrating the longevity and sustainability of the program.

Some months ago, the medication safety team circulated a survey among the staff asking for feedback on the recognition program. Among the survey responses, staff asked the team to choose appropriate event reports that have already been closed and walk through the full error investigation and analysis process, so that the staff could understand how the team investigates events and makes suggestions for system changes. The medication safety team immediately began work on that request by scheduling a 30-minute clinical rounds every four weeks. During the clinical rounds, a member of the medication safety team goes through a de-identified report with attendees. This has been a fantastic opportunity to introduce staff to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices’ 10 key elements of an error (Institute for Safe Medication Practices, n.d.). It follows that as the staff continues to analyze reports, they will become even better at identifying risk. Feedback from the pharmacy staff has been enthusiastic and resulted in development of more robust process improvements for the errors discussed.

Conclusion. The medication safety recognition program designed for Concord Hospital incorporates many best-practice components (Chen, n.d.). Upon the program’s introduction, the medication safety team engaged pharmacy leaders to help decide the program’s goals and rewards. The team tied the recognition program’s goals to the medication safety strategic plan to directly support that program. The team also chose very clear metrics at the beginning so that success could be monitored and reported. Over time, any program can become stagnant, so the program welcomes and routinely requests feedback from staff to ensure it continues to evolve. Each new employee receives an introduction to the medication safety program during their onboarding to impress upon them the program’s importance and permanence. Lastly, departments and individuals that achieve their goals receive congratulations verbally, in writing, and with a celebration. All of these characteristics help to make sure that the recognition program will remain relevant over time.

Stephanie D. Yarbrough-Morgan, PharmD, BCPS, is a medication safety pharmacist in the Pharmacy Department at Concord Hospital. Elizabeth Wade, PharmD, BCPS, FASHP, is the patient safety officer for Amazon Pharmacy.

References

Chen, J. (n.d.). 18 employee engagement best practices in 2022. Teambuilding. www.teambuilding.com/blog/employee-engagement-best-practices

Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (n.d.). Key elements of medication use. www.ismp.org/key-elements-medication-use

National Patient Safety Foundation. (2015). RCA²: Improving root cause analysis and actions to prevent harm. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/RCA2-Improving-Root-Cause-Analyses-and-Actions-to-Prevent-Harm.aspx

Smith, R. (2013, June 1). Effective safety recognition programs: The do’s and don’ts. Occupational Health and Safety. www.ohsonline.com/Articles/2013/06/01/Effective-Safety-Recognition-Programs.aspx