Introduction of Wireless Buzzer to Improve Efficiency in Gynecology Triage

By Nicholas Stansbury, MS4, and Erin Nelson, MD

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of the study was to determine if a restaurant-style buzzer to notify students when to interview patients would streamline workflow.

Design: A Plan-Do-Study-Act approach was used. The project was introduced during clerkship orientation. Nurses would use the buzzer to alert students when to begin patient interview. Buzzers were provided for three weeks of the rotation. During the other three weeks, no buzzers were provided as an internal control.

Setting: The current workflow in gynecology triage has medical students interviewing patients after triage by nurses. The optimal time to initiate patient contact is unclear for students. This confusion has led to duplication of questions to patients, interruptions for nurses, and fewer patient encounters for students.

Participants: Stakeholders were medical students, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians. Nurses and medical students were the main participants.

Measurements: After each clerkship, students received a survey assessing key areas of waste and workflow disruption.

Results: From February to July 2019, 30/45 surveys were completed (66%), answering the following questions: 1. “How difficult was it to determine the proper time to begin the patient encounter?” 2. “How often were patients asked the same questions by nurses and medical students in separate interactions?” 3. “How often did you interrupt nursing staff during their triage of a patient?” 4. “How many patients did you interview in nurse triage on average per day?”

- Responses of “very difficult” or “difficult”: 90% without buzzer; 21.4% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Responses of “very often” or “often”: 96.7% without buzzer; 14.8% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Responses of “very often” or “often”: 76.7% without buzzer; 18.5% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Odds of interviewing five or more patients per shift: ~10 times greater using the buzzer (χ² = 14.2; p < 0.001)

Conclusion: Introduction of a simple, low-cost restaurant-style buzzer for nurses to notify students to begin patient interview improved triage workflow by increasing patient capacity and decreasing nursing interruptions.

Introduction

The current workflow in gynecology triage has medical students interviewing patients after they have been triaged by nursing staff so as not to cause disruption. However, several problems occur with this workflow. There is increased nursing frustration due to students re-asking questions that patients already answered during nurse triage. Students interview fewer patients and often interrupt nurses due to not knowing the optimal time to arrive at patient triage. This leads to frustration and hindered learning for students while disrupting nurse and resident workflow.

Medical students have adopted several strategies to solve this challenge: sitting in the hallway where they can see patients enter triage, sitting in nurse triage, continually refreshing the EMR to see if a patient has checked in, or walking back and forth from their workstation to talk to the nurses about when the next patient will be brought in. Unfortunately, these adaptations have created problems of their own. Students become frustrated due to wasted time spent checking for patient triage instead of actually interviewing patients or doing hands-on procedures. In addition, while sitting in nurse triage, students are in the way of nurses and are physically remote from residents so they cannot be of assistance or help out with procedures, which has resulted in nurse, student, and resident frustration.

A novel idea of utilizing a restaurant-style buzzer to notify students when the nursing staff is ready to do their initial triage and when it is appropriate for the students to begin the patient encounter was proposed.

Materials and methods

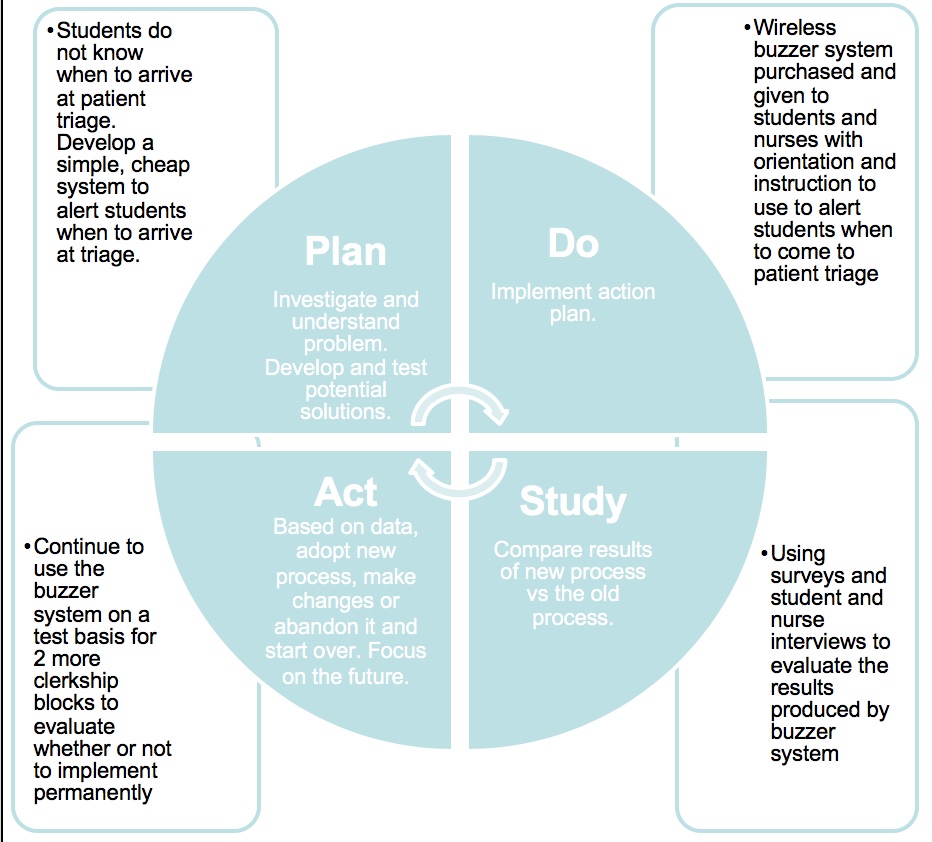

Using the quasi-experimental PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) cycle approach (see Figure 1), a restaurant-style buzzer was introduced to improve workflow in gynecology triage.

Figure 1. Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle

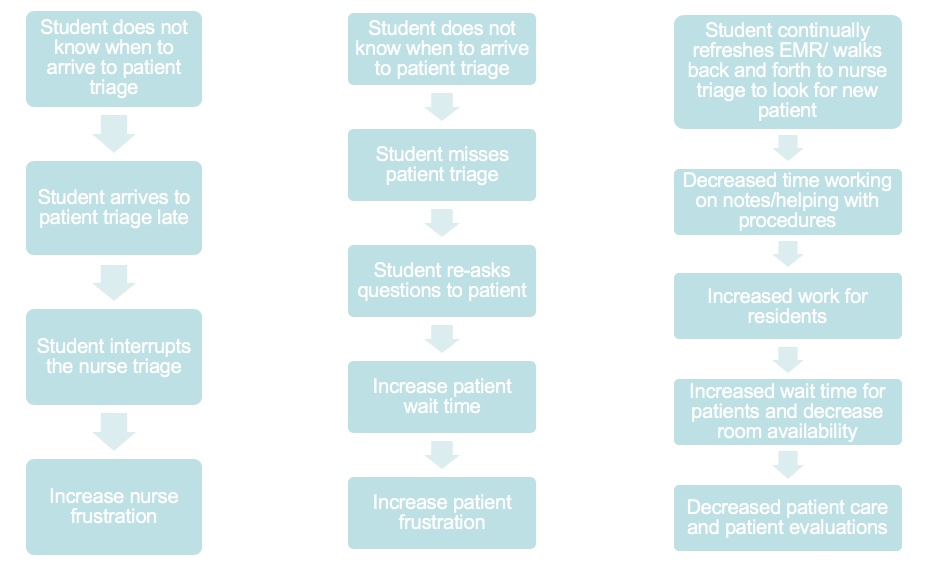

Stakeholders, which included third-year medical students, nursing staff, advanced practice nurses, and physicians, identified and engaged with the project. With the use of a simple process flow diagram (see Figure 2), the factors identified as potentially contributing to workflow slowdown included: students re-asking questions of patients that were already answered during nurse triage, students not knowing where patients were in the triage workflow and interrupting nursing staff, and fewer interviews completed by students who simply stopped trying due to feeling frustrated or overwhelmed.

Figure 2. Simple Process Flow Diagram

A wireless system was purchased (the “Wireless Caregiver” call button system, manufactured by HSTYAIG).

Students and nurses were provided instructions (via email) that included a basic review of how to use the buzzer system, an explanation of the project, and a timeline by the primary study investigator (NS). Students were given a formal orientation to the project at the start of their OB-GYN clerkship, and nursing staff were oriented in person on a shift-by-shift basis by study investigators (NS and CC). Buzzers were provided to students for use on weeks 1, 3, and 5 of the clerkship rotations beginning January 2019, and weeks 2, 4, and 6 were conducted without the buzzers to serve as an internal control and compare the same students’ experience in triage with and without the buzzer. Weeks 1–3 did not serve as an internal control since students switch to the obstetrics service after three weeks. Nursing staff were asked for opinions and feedback on the project weekly, and students were informed of any necessary modifications in protocol via email. After each six-week clerkship, students were given a survey assessing key areas of waste and workflow malfunction.

Results

A total of 30 surveys were completed out of 45 for a completion rate of 66%, answering the following questions:

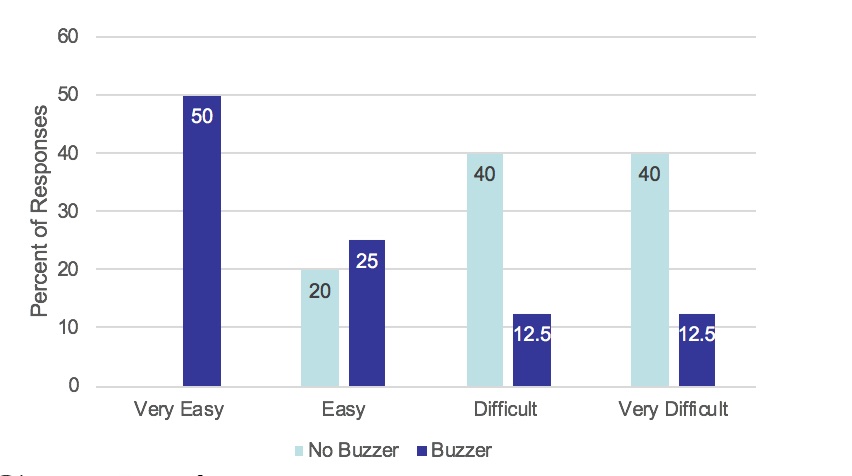

Figure 3. How difficult was it to determine the proper time to begin the patient encounter?

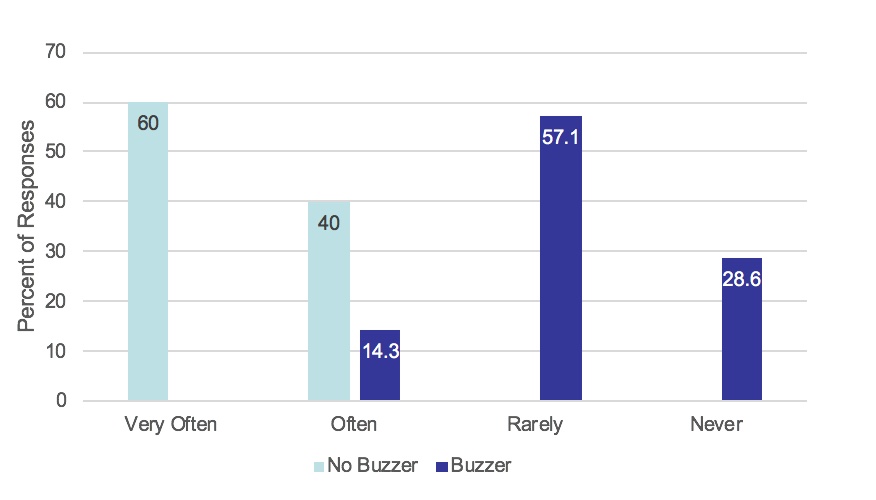

Figure 4. How often were patients asked the same questions by nurses and medical students in separate interactions?

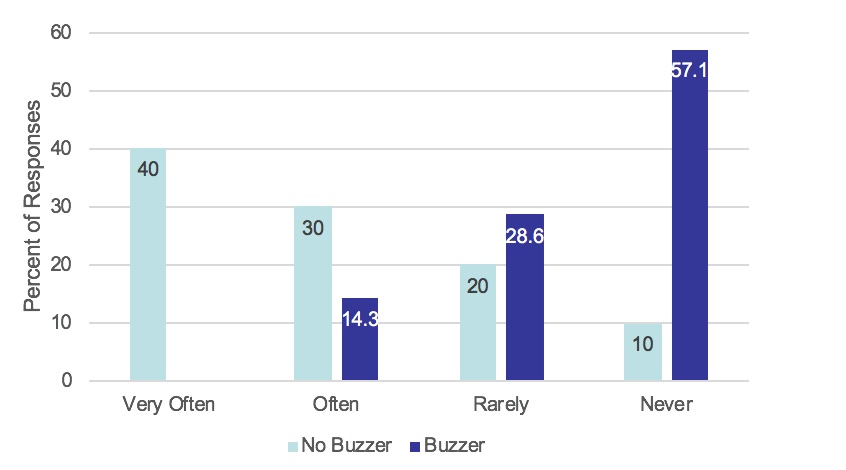

Figure 5. How often did you interrupt nursing staff during their triage of a patient?

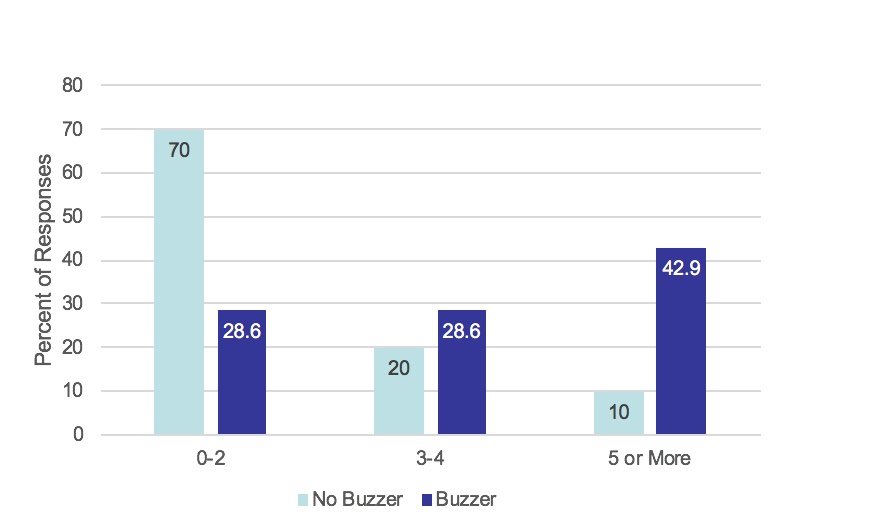

Figure 6. How many patients did you interview in nurse triage on average per day?

Without the buzzer, 90% of students found it very difficult or difficult to determine when to begin the patient encounter; however, with the buzzer, only 21.4% of students found this very difficult or difficult (see Figure 3). Without the buzzer, over 96% of students re-asked questions of patients very often or often. Yet, with the buzzer, less than 15% of students did so (see Figure 4). Without the buzzer, nurses were very often or often interrupted by medical students over 75% of the time; however, with the buzzer, they were interrupted at this frequency less than 20% of the time (see Figure 5). Finally, the odds of medical students interviewing five or more patients per shift were around 10 times greater using the buzzer compared to not using the buzzer (see Figure 6). The complete results were as follows:

- Responses of “very difficult” or “difficult”: 90% without buzzer; 21.4% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Responses of “very often” or “often”: 96.7% without buzzer; 14.8% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Responses of “very often” or “often”: 76.7% without buzzer; 18.5% with buzzer (p < 0.001)

- Odds of interviewing five or more patients per shift: ~10 times greater using the buzzer (χ² = 14.2; p < 0.001)

Discussion

The buzzer system did present challenges. Initially, buzzers were sometimes left unattended in the resident workroom, leading them to automatically shut off; sometimes a student would inadvertently alter the buzzer to play a tune that was too long/loud, which led to the buzzers being turned off. Despite our efforts, some nursing staff did not know of the project or simply forgot to press the buzzer to alert students to begin the patient encounter. These issues were addressed via improved communication strategies (electronically and in person), and the setbacks decreased as the project continued.

The project ran from January to May until it was instituted full time as part of the everyday workflow for nurses and third-year medical students on the OB-GYN clerkship in gynecology triage.

Conclusion

Introduction of a simple, low-tech restaurant-style buzzer improved triage workflow. Both students and nursing staff reported satisfaction with the system, and the data clearly indicated an increase in capacity and consistency. Students perceived less wasted time in their day, experienced less frustration with the process, and saw more patients, while nurses noted a drastic decrease in interruptions by medical students.

We are considering other ways in which the low-cost buzzer system could improve processes in gynecology triage—for example, having a separate buzzer system for medical techs who chaperone pelvic exams, since they may be busy with other patient care tasks when the time comes to perform the exam.

Nicholas Stansbury is a fourth-year medical student at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine and was elected to the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society in 2019. He will begin his OB-GYN residency in July 2020. Erin Nelson is certified in Obstetrics and Gynecology, serves as a board examiner for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and is the MS3 clerkship director at UT Health San Antonio Long School of Medicine.