ECRI Institute PSO Deep Dive™ Analyzes Medication Events

September / October 2012

![]()

ECRI Institute PSO Deep Dive™ Analyzes Medication Events

Medication mishaps are the most common errors in healthcare (IOM, 2006). The sheer number of drugs administered in healthcare facilities increases the likelihood that medication errors will occur if risk reduction systems are not in place. Additionally, the medication-use process is complex, encompassing several phases, including (but not limited to) prescribing, dispensing, administering, and monitoring.

By analyzing their medication errors—both actual events and close calls, or near misses—healthcare organizations can identify the risks in their medication-use practices that allow errors to occur and apply lessons to prevent their recurrence. But this process can be slow because an organization must collect enough meaningful data to spot problems and trends.

The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 created a framework for healthcare providers to improve patient safety by sharing data with federally certified patient safety organizations (PSOs) that provide analysis and feedback regarding patient safety matters in a protected legal environment. In 2011, ECRI Institute PSO, which was among the first federally certified PSOs, spearheaded a unique collaborative for healthcare organizations to learn from medication errors, which represent the most frequently reported events submitted to ECRI Institute PSO—comprising about 25% of all events.

ECRI Institute PSO asked the participating healthcare organizations to submit at least 10 medication events—either actual errors or close calls (near misses)—over a specified five-week period so that the PSO could identify patterns and trends from the aggregated, de-identified data and share the findings, as well as recommendations. ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive™ of these medication events uncovered lessons to reduce the frequency and severity of errors related to medication use and to make medication safety an ongoing focus. (See the sidebar, “Taking ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive Deeper” for more information on how one healthcare organization used the findings.)

While the analysis, ECRI Institute PSO Deep Dive: Medication Safety, represents a snapshot of medication errors, there is much that can be learned to improve medication safety. The analysis found that events occurred most frequently during the administration stage of the medication-use process. To be effective in reducing administration errors, ECRI Institute PSO recommended that facilities harness a combination of techniques to address the various types of errors involved with the top-three problematic routes of administration—intravenous (IV) infusions, oral medications, and subcutaneous injections.

Call to Action

In March 2011, ECRI Institute PSO issued a call to action to its member organizations and members of its partner PSOs to collaborate in its Deep Dive initiative to learn from medication errors and to share strategies to reduce errors and improve care within member facilities. Participating organizations submitted 695 medication events during the five-week period starting April 15, 2011, and ending May 20, 2011. Eighty healthcare organizations—including general acute care and pediatric hospitals and long-term care facilities—joined the initiative; the majority of events were submitted by acute care hospitals.

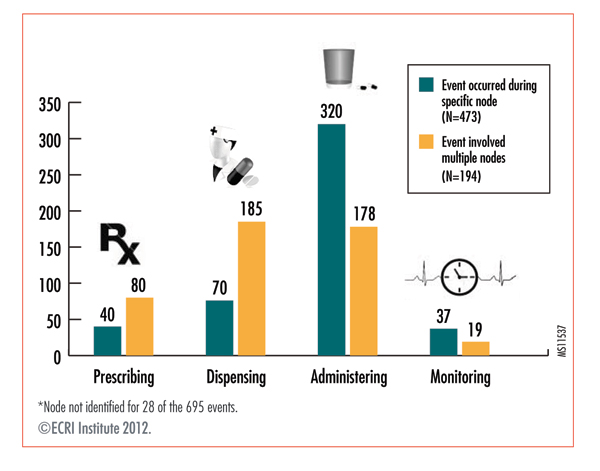

Most events occurred during the medication administration stage or “node” of the medication-use process. Although errors can occur in any phase of the medication process, participating facilities indicated that most events specific to one node (473) occurred during administration of the medication (67.7%), followed by dispensing (16.1%), prescribing (8.5%), and monitoring (7.8%) (See Figure 1).

Some events occurred during multiple nodes of the medication-use process. For example, an error in the ordering stage may continue into the dispensing and administration nodes. When events involved multiple nodes of the medication-use process (194), the majority of events occurred during both the dispensing (95.4%) and administering nodes (91.8%). When the percentage of all events occurring during each of the four nodes—regardless of whether the event arose during a specific node or multiple nodes—are calculated, events happened most frequently during the administration node (71.7%), followed by dispensing (37.6%), prescribing (17.3%), and monitoring (8.1%). Refer to the figure to see how the events were distributed by node.

|

Taking ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive™ Deeper A Tennessee hospital system used ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive™ into medication safety to validate key findings from a system-wide initiative on its medication processes and to dive deeper into these findings. Baptist Memorial Health Care, Memphis, Tennessee, is a member of the Tennessee Center for Patient Safety PSO (TCPS PSO), which participated in ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive analysis of medication events. The Deep Dive dovetailed with Baptist’s ongoing medication-use initiative, begun about 10 years ago and involving representatives from pharmacy, nursing, and risk management at the system level, as well as subgroups from its 14 hospitals in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee. When ECRI Institute PSO’s Deep Dive report and toolkit were released, Baptist Memorial requested a presentation about the findings for its medication-use system team (MUST). ECRI Institute PSO’s liaison to the TCPS PSO presented the information by webinar to the team. Additionally, the report and toolkit were provided to all of Baptist’s MUST members, including each hospital’s subgroup team members. The team found that the Deep Dive corroborated its own findings about errors involved drug omissions, or the failure to give an ordered dose. The team’s previous review of the medication-use process had identified medication omissions as a target area for improvement. The system’s review of six months of data found that medication omissions occurred more frequently on Mondays through Thursdays during the hours of 4 to 6 p.m. and 8 to 10 p.m. and involved the electronic medication administration record system. As a result of the findings from ECRI Institute’s Deep Dive, Baptist’s MUST members decided to dive further into its medication omissions and provided each hospital with facility-specific data on its omissions for the previous five years. Each facility’s MUST subgroup is using the data to identify medication omission trends and patterns involving days of the week, time of day, medication processes, and electronic medical and medication administration records. |

ECRI Institute PSO’s analysis looked at the medication administration events by route of delivery and found that of the 320 reports for administration-only errors, IV-related errors were the most frequently occurring events, representing 36.9% of administration-only events, followed by oral administration events (18.1%) and subcutaneous injection (7.8%). The analysis dove deeper into these events to understand the reasons and prevention strategies for each type of medication administration error.

Intravenous Administration Errors

The frequency of IV administration errors may be due partly to the frequency of IV use and the complex, error-prone aspects of infusion pump programming. In some hospital units, as many as half of all medications that a nurse administers are delivered intravenously. Because the devices are programmed at the bedside and have a range of programming options, IV therapy is prone to mistakes. It is possible to leave out a decimal point or add a zero when setting the infusion rate, resulting in a 1- or 100-fold overdose. The small screens on some pumps can increase the risk of selecting the wrong medication or dose. Additionally, there is increased risk of error because of variability in the names of drugs used for infusions, dosing concentrations, dose limits, and infusion rates.

Many IV infusions involve high-alert drugs, such as insulin, anticoagulants, and chemotherapeutic agents. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), which publishes a list of high-alert medications, defines them as drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant harm when they are used in error (ISMP, 2012). Of the 118 IV-related administration errors, 55 (46.6%) involved a high-alert medication, and 9 of the events, according to the reports, resulted in patient harm, including two deaths. Significantly, these two fatal events were the only two medication errors reported that may have contributed to or resulted in patient deaths; both occurred during administration of IV infusions, and both events involved high-alert medications.

ECRI Institute PSO also found that among the 118 IV-related medication errors, the most commonly reported types were for the following reasons:

- Drug not given (22.9% of IV-related errors)

- Wrong pump rate (20.3%)

- Wrong drug (16.9%)

- Wrong dose (13.6%)

Drug not given. Several events described delays in administering a piggyback IV medication because of failure to open the tubing clamp so that the medication could be infused through the main IV line, as in the following report:

The IV antibiotic was hung but did not infuse because the tubing was clamped to the secondary set.

Sometimes, a caregiver simply forgot to connect the IV line to the patient.

Wrong rate. Several wrong-rate events involved programming the pump to deliver an infusion at the wrong rate, as in the following report:

Levophed (norepinephrine bitartrate) was administered at an incorrect rate. The nurse ran the Levophed at the maintenance IV rate instead of the correct, and much slower, rate.

Programming errors have the potential for harm if the wrong amount of medication—either too much or too little—is delivered. In the above case, the programming error resulted in the patient receiving too much of a high-alert medication—Levophed is an adrenergic agonist—although according to the report, the patient was not harmed.

Programming errors that result in drug dosing errors can be difficult to detect unless the organization uses newer infusion pumps that incorporate medication safety software like drug libraries with dosing limits to warn users of programming errors before IV medications are administered. In one report, a rate-programming error resulted in the patient receiving 100 times the amount of heparin that was ordered:

The nurse programmed the pump with heparin to run at 200 cc/hour versus 200 units/hour, or 2cc/hour.

Heparin is another high-alert medication and can cause patient harm or death from overdoses of the blood-thinning agent. In the event reported, the patient was monitored for any adverse effects.

Errors in calculating the patient’s weight can also lead to pump-rate errors.

Wrong drug. The infusion events analyzed by ECRI Institute PSO underscore the risk of administering the wrong drug in an infusion. One such event may have contributed to or resulted in a patient death when the patient was given a wrong-drug infusion of lidocaine, a high-alert antiarrhythmic:

A patient was given an IV infusion of lidocaine for arrhythmia. When the IV infusion was discontinued, the patient was to receive saline intravenously. Later, a nurse found the patient had pulled the IV line and was unresponsive; it was discovered that the lidocaine bag was empty, and the saline bag was full.

Another wrong-drug IV infusion error was nearly fatal because the patient mistakenly received a paralyzing agent—succinylcholine, a high-alert medication—instead of ketamine, a general anesthetic. Because paralyzing agents can affect the muscles for breathing, a patient who receives succinylcholine requires a ventilator. A patient receiving ketamine can still breathe spontaneously and need not be ventilated. In the following case, the patient was not on a ventilator when succinylcholine was mistakenly given:

The [anesthesia provider] mistakenly grabbed a syringe containing succinylcholine instead of ketamine. Although the medication label on the syringe was correct, the syringe was supposed to be stored separately and have an orange warning label. The [anesthesia provider] attributed the error to being in a hurry and lack of a warning label.

Wrong-drug IV errors occurred for a variety of reasons: a verbal order was misheard, and the order was not read back for confirmation; the wrong infusion drug was mistakenly pulled from an automated medication dispensing cabinet because it was in the wrong bin; or the wrong IV fluid was hung without double-checking the contents of the infusion bag.

Oral Administration Errors

Events occurring with medications delivered by mouth sometimes involved similar errors as those found among the IV events. The following reasons were given for the 58 events involving oral medications:

- Wrong dose (29.3%)

- Drug not given (20.7%)

- Wrong drug (15.5%)

Though there were wrong-patient errors for events involving both IV and oral administration of drugs, the wrong-patient errors represented a larger share of events for medications taken orally—10.3% for oral administration events versus about 6% for IV-related events.

As with IV events, a large share of oral administration events involved high-alert medications (39.6%). The largest number of events with high-alert medications, 12 or 52.2% of the events, occurred with opioids, and another 5 events (21.7%) arose with anticoagulants.

Examples of events reported for oral medications are given below by type of event.

Wrong dose. Among the immediate causes of the 17 wrong-dose errors for medications administered orally were caregiver distraction and inaccurate information about a patient’s weight. In the following report, the caregiver mistakenly doubled a patient’s dose of lorazepam:

The nurse inadvertently misread a medication order for 0.5 mg of lorazepam as two lorazepam 0.5 mg and administered 1 mg.

Drug not given. In the following report, a transcription error resulted in a patient missing a drug dose:

A physician’s order for a medication was omitted from the medication administration record (MAR). The error was found during the night shift chart check. The prior day’s medication dose had been omitted.

Other errors involved drug omissions or the failure to give an ordered dose, resulting in problems requiring additional care.

Wrong drug. The nine wrong-drug events of oral medications occurred for a variety of reasons: the automated dispensing cabinet had the wrong medication; one medication was incorrectly substituted for another; a patient, who indicated an allergy to hydromorphone, was still given the opioid, a high-alert medication; and a patient was given several different medications without a physician’s order, resulting in temporary harm.

Wrong patient. When reasons were given for any of the six wrong-patient drug errors for oral medications, they included the following: the drug was mistakenly administered to the intended patient’s roommate, the patient was not identified by name before the drug was administered, and the nurse had multiple patients on varying doses of the same medication and gave the wrong dose to one of the patients.

Drug Injection Administration Errors

Of the 25 events occurring with a subcutaneous injection of a drug, wrong-dose errors represented 36%, followed by wrong-drug errors (20%) and drug-not-given events and delays in administering an injection (both categories represented 12% of events involving subcutaneous injections). Significantly, 88% of the events entailed a high-alert medication—either insulin or anticoagulants, such as heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin.

For example, one report described a near-miss, wrong-dose event with insulin:

A sliding-scale insulin regimen was supposed to be discontinued but remained in the MAR the following day.

In another report, a patient received too much of a low-molecular-weight heparin because the patient’s recorded weight was misrepresented as kilograms rather than pounds:

Lovenox (enoxaparin) was given based on 1mg/kg and administered every 12 hours. The patient’s weight was recorded as 114 kg rather than the actual weight of 52kg (114 pounds), resulting in a medication overdose.

Looking Beyond Individual Performance

With many administration events, there is a mistaken tendency to focus primarily on the individual performance of the nurse who gave the medication. Consider the following report submitted for the Deep Dive, which cited the nurse’s lack of experience as contributing to the event when illegible handwriting and transcription errors were more likely the cause:

The handwritten transcription of an order in the MAR incorrectly stated the patient was to receive 2.5 mg of methotrexate weekly. The nursing student administered this amount. The actual dose should have been 20 mg, or 8 tablets of methotrexate, each containing 2.5 mg.

To prevent medication administration errors, nurses are often reminded to adhere to the “five rights” of safe medication administration: right patient, right drug, right time, right dose, and right route of administration. Focusing solely on the five rights of medication administration ignores the human factors and systems-based causes of errors. Without measures to help caregivers administer medications safely, errors will occur. How can a nurse provide the right dose of a new medication if information about the medication or a pharmacist is not readily available? Isn’t a mistake more likely to occur if two patients with the same last name are admitted to the same hospital room?

A human factors approach analyzes an individual’s performance within the context of the surrounding environment. A nurse who accidently misprograms an infusion pump by omitting a decimal point may still think that the setting is correct, even after checking the display. Human factors researchers call this confirmation bias, underscoring the importance of independent double checks. Asking another nurse to independently check the infusion dose and confirm the setting can reduce the likelihood of error.

A systems approach to safety views accidents as the result of multiple faults within a system that occur together in an unanticipated interaction. Did poor lighting, inadequate staffing, or poorly designed medical devices, along with a long list of other systems issues, create a situation that enabled the error to occur?

Hierarchy of Error-Reduction Techniques

A medication safety plan must, therefore, focus on identifying the issues that set people up to make mistakes and develop strategies to help them “do the right thing” and prevent those mistakes from occurring or lessen their harm.

Experts in system safety have developed a hierarchy of error-reduction techniques based on the impact that they can have in preventing errors. The high-impact strategies, which “design out” the hazard, are considered the most powerful and most desirable strategies because they can eliminate hazards. For example, an organization can reduce the risk of medication overdoses by dispensing medications in single-dose units only. High-impact strategies also incorporate fail-safe mechanisms and forcing functions that provide a barrier or safeguard to prevent a hazard from adversely affecting the process. An example of a forcing function is an infusion pump that will not allow delivery of an infusion if a programmed dose exceeds preset limits.

Moderate-impact strategies do not eliminate a hazard but use techniques, such as standardization, process simplification, warnings, and alarms, to reduce the likelihood that errors will occur. While effective, these error-reduction techniques are rated as moderate because they are highly dependent on the behavior of people using the system. For example, audible alarms on infusion pumps increase caregivers’ ability to detect possible errors. But if the audible alarm on an infusion pump is set to a low volume so that a sleeping patient is not disturbed, nurses at a nearby nursing station may never hear the pump alarm.

|

ECRI Institute ECRI Institute, a Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania-based nonprofit organization, dedicates itself to bringing the discipline of applied scientific research to healthcare to uncover the best approaches to improving patient care. ECRI Institute PSO was officially listed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as a federal patient safety organization in 2008. For more information, contact Barbara Rebold at brebold@ecri.org or Karen Zimmer at kzimmer@ecri.org. |

Low-impact strategies use special policies and procedures and education to reduce errors. For example, a policy requiring annual training on IV infusion safety is intended to ensure the competency of nurses who administer IV medications. By itself, the policy will not prevent mishaps, but, in combination with other measures, such as using infusion pumps with forcing functions, it will contribute to overall safety.

The hierarchy of error-reduction techniques emphasizes that there is no one solution to prevent medication administration errors. Healthcare organizations must consider various high-, moderate-, and low-impact approaches and choose those safety strategies that will have a higher impact in preventing medication administration errors as often as possible. The goal is to redesign the medication-use process to make it harder for errors to reach the patient.

ECRI Institute PSO grouped the recommended medication administration safety strategies by their impact—whether high, medium, or low—in preventing errors. These strategies are listed in the chart “Risk Reduction Strategies to Improve Medication Safety by Strength of Impact,” which appears online at http://psqh.com/pdfs/Risk_Reduction_Strategies.pdf. Using the list of recommended risk reduction strategies, ECRI Institute PSO also prepared a toolkit for its participating facilities to consider each safety strategy for medication administration discussed in its Deep Dive analysis, identify any action required by the facility, and assign a deadline for implementation.

Charlotte Huber is associate performance improvement manager at Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, and served as senior patient safety analyst and consultant for ECRI Institute PSO when the Deep Dive analysis was conducted.

Barbara Rebold is director of operations for ECRI Institute PSO as well as director, INsight™ Assessment Services at ECRI Institute.

Cynthia Wallace is senior risk management analyst with ECRI Institute’s Patient Safety, Risk, and Quality Group.

Karen Zimmer is the medical director for ECRI Institute PSO and ECRI Institute’s Patient Safety, Risk, and Quality Group.