Delivering the Promise to Healthcare: Improving Patient Safety and Quality of Care Using Aviation CRM

July / August 2005

Delivering the Promise to Healthcare

Improving Patient Safety and Quality of Care Using Aviation CRM

The application of proven aviation crew resource management (CRM) technology and training to the reduction of medical errors is a steadily emerging area of human factors. Recently, various research teams have begun publishing reports and compiling data to support the benefits of applying CRM principles to the patient care process. This article summarizes data published in research reports and reviews the quantitative and qualitative benefits of implementing CRM in the healthcare environment.

CRM research data related to patient safety, process improvement, and medical error reduction validate its effectiveness in healthcare. Patient Safety Committees (PSCs) have been formed to address safety concerns within hospital organizations. Typically the PSC includes the hospital CEO, risk manager, doctors, nurses, legal, pharmacy, diagnostics, and other support staff. The PSC members are the change agents to bring healthcare CRM research from the labs and universities into clinical settings. With the support of a healthcare CRM practitioner, these change agents can affect a paradigm shift in their hospital organizations resulting in measurable improvement in patient safety and quality of care.

Aviation CRM has been in use for more than 20 years with unparalleled safety results in both military and civilian aviation. Volumes of research reports and application evidence support the effectiveness of Aviation CRM. During the past 10 years, human factors research teams in aviation have joined with prominent medical researchers to create the Foundation for Healthcare CRM. The leading Healthcare CRM research teams are from the University of Texas Human Factors Project, Stanford University, and the Crew Performance Group at Dynamics Research Corporation.

Aviation CRM Successes

Aviation CRM has been extremely effective in changing behaviors and attitudes in the cockpit (Helmreich, et al., 1999). Many of these changes came about through better communication, decision-making, and overall improved teamwork. The shared mental model was used to create briefings that share intentions, enhanced planning, and increased overall situational awareness (Helmreich, et al., 2001). Situational awareness is the anticipation and recognition of current events or events likely to occur in the near future (Endsley, 1995).

Decision-making improved because the captain as team leader had “shared” information on which to base decisions. Overall, better teamwork resulted from breaking down barriers between workgroups. The steep hierarchal structure of the captain as “king” of the aircraft began to flatten with the introduction of CRM (Helmreich, et al., 1993). This resulted in better crew coordination not only in the cockpit but also with the flight attendants whose important role expanded to include safety of flight. An expanded team was now working towards a common goal of safe flight operations. The captain was still king, but instead of providing 100% of decision-making, he now had 51% after consideration of all inputs. CRM became so successful that it was mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and became the benchmark for crew evaluations during certification events. Aviation CRM has evolved over this period into its current version of threat-and-error management that attempts to identify and capture errors before they result in an unsafe aircraft situation (Musson, et al., 2004).

Similar Behaviors and Attitudes in Medicine

Data indicate that behaviors and attitudes in the operating rooms, emergency rooms, and intensive care units are similar in nature to attitudes that existed in cockpits before CRM. Surgeons as “kings” are the most likely to resist the flattening of steep hierarchies on their surgical teams (Sexton, et al., 2000). Since medical training focuses on individual skills and performance, physicians tend to practice medicine as individuals (Shapiro, et al., 2004). Steep hierarchies tend to place most of the decision-making process with the doctor and result in staff being reluctant to share valuable information. The attitude of one team member toward another can be enough to change the effectiveness of the entire team.

Doctors perceive teamwork and communication to be better than other team members. Sexton et al. (2000) found that other team members (nurses, anesthetists, and support staff) reported high levels of team effectiveness only 40% of the time whereas surgeons reported high levels of team effectiveness 77% of the time. Sexton, et al., also report that communicating errors within the team is impeded because of personal reputation (76%), threat of job security (63%), and the egos of other team members (60%). Doctors and nurses (60%) believe that they perform effectively even when they are fatigued.

Challenges Facing Healthcare

CRM researchers define error as “an inevitable result of the natural limitations of human performance. (Helmreich, et al., 1999)” Doctors and nurses are less likely to recognize the inevitability of errors. In intensive care units, 30% of doctors and nurses denied committing errors (Sexton, et al., 2000). The Institute of Medicine report on medical errors (2000) shows more patients (44,000 to 98,000) die annually from preventable medical errors than die from AIDS, automobile accidents, or breast cancer. Medical errors in the U.S. cost $37.6 billion annually with preventable errors accounting for $17 billion of that total. Adverse drug effects (ADEs) result in over 770,000 people injured or dead each year in hospitals, which may cost up to $5.6 million each year per hospital depending on the hospital size (AHRQ, 2001). The cost of litigation resulting from medical errors has risen rapidly. In 2000, the median malpractice award increased 43% to $1 million. Some malpractice insurance premiums have increased 20% to 100%, to over $100,000 for some specialists like ob-gyns (PwC, 2002, pg. 8). A study of risk management cases involving emergency departments revealed that 43% of errors were due to problems with team coordination (Shapiro, 2004).

Solutions Using CRM in Healthcare

Healthcare CRM begins with the collection and analysis of hospital patient safety data. The analysis of this data defines the CRM training tasks required for the individual hospital and will measure program success. The hospital organization must have a “shared values” and “leadership by example” safety culture that begins with the CEO and permeates to the lowest staff level. This culture must support systemic error identification instead of individual error punishment (Singer, et al., 2003). Individuals should only be held accountable when they purposely violate standard operating procedures (SOP) (Helmreich, et al., 2001). Healthcare CRM team training involves defining the team, understanding basic human factors, and applying the knowledge to case studies and eventually the workplace. Feedback must be provided throughout the training through surveys, interviews, and observations. Coaching is provided during extensive individual and team debriefs following observed CRM performance (Morey, et al., 2002). This type of debrief follows a path of an error through a process model or decision tree to capture, identify, and mitigate errors before they result in an adverse patient outcome (Helmreich, et al., 2001).

Implementing Healthcare CRM in the Organization

One such program is Healthcare CRM, which consists of six building blocks of CRM team training and evaluation.

- Block 1 consists of a survey of the organizational safety culture, the patient flow process, and a review of any internal safety concerns of the organization. Mutually agreed upon metrics are established to measure program performance. The next phases are customized for the organization based on this collected and analyzed data.

- Block 2 is CRM team training, which discusses command, leadership, communication, situational awareness, decision-making, resource management, and workload management. Facilitated discussions using actual adverse event case studies and interactive team exercises are conducted.

- Block 3 allows newly formed teams to apply the knowledge gained in Block 2 to job specific case studies and simulations through targeted workshops including comprehensive team briefings that discuss procedure details as well as possible contingencies including nurse shift changes. Organizational change agents are identified who have strong communication and team-building skills to become future Healthcare CRM program practitioners.

- Block 4 is designed to measure CRM skills in real time through facilitated debriefs following actual medical procedures.

- Block 5 is the coaching phase where procedures such as briefings and checklists are reviewed. Error reporting and analysis systems are examined or created for future program improvement and data analysis. The organization begins the process of creating their future CRM training program in-house through train-the-trainer programs.

- Block 6 reports the outcomes and metrics established as a result of CRM training. Future training is planned as part of an in-service training cycle. Other identified groups are targeted for future CRM training. Depending on the group size and scheduling of the phases, program implementation should take from 6 to 12 months to complete.

Adding Value Through CRM

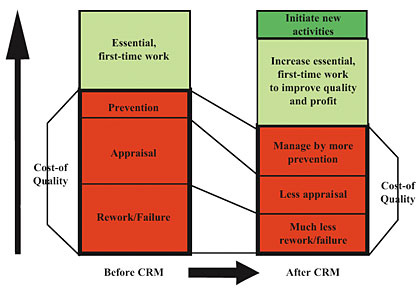

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) currently suggests team training be part of the patient safety program. JCAHO recognizes that effective teams perform their work more efficiently. In one year, the average length of stay at a major hospital’s ICU was reduced by 50% after implementation of healthcare CRM, resulting in $7 million of additional revenue from increased efficiency (Lazarou, 2003). Also, hospitals reported a significant reduction in medical error rates. At one hospital, adverse outcomes for ob-gyns declined by 53% over a four-year period, suggesting that communication and teamwork can make childbirth safer (ACOG, 2004). A study of emergency department (ED) staff showed a 58% reduction in observable errors after healthcare CRM implementation (Shapiro, et al., 2004). As errors are reduced, patient safety officers and risk managers can spend less time investigating an adverse patient treatment and more time proactively identifying threats before they become errors (Kuhn, et al., 2002). Figure 1 illustrates how medical teams trained in healthcare CRM can perform more work at a lower cost of quality without compromising patient safety (Garrison, 2003).

![]()

After CRM, malpractice insurance rates for individual doctors and cost-of-risk associated with professional liability coverage should be reduced for hospitals. A closed claim review of ED errors revealed that after CRM training the projected liability cost savings averaged $3.45 per patient visit (Shapiro, et al., 2004). Nurses have probably been the strongest advocates of CRM. Nurses report a higher level of respect from doctors after CRM. Job satisfaction is elevated as nurses believe their input is more valued by the doctor. Hospitals with high nursing turnover rates had 36% higher costs per discharge than hospitals with turnover rates of 12% or less. Hospitals with a lower rate of turnover also had lower risk-adjusted mortality scores as well as lower severity-adjusted length of stay compared to hospitals with 22% or higher nursing turnover rates (Gelinas, et al., 2002).

Delivering the CRM Promise to Healthcare

Every successful organizational change occurs from within through the use of change agents. Additional impetus for change comes externally from JCAHO, the hospital board of trustees, or safety minded individuals; but, for Healthcare CRM to be successfully implemented, the organization has to create and manage the change through the Patient Safety Committee (PSC) structure. A patient safety officer (PSO) leads this committee. The PSO is usually a clinician possessing a unique set of skills to integrate all the various workgroups towards a common safety goal. The initial CRM training provider should be a team of professionals consisting of researchers, aviation CRM professionals, doctors, nurses, risk managers, and Healthcare CRM practitioners. Eventually, train-the-trainer programs for organizations can lead to a self-sustaining CRM program within a hospital. Dr. Clifford, MD, UCLA, may have said it best about delivering the promise of patient safety: “Safety means the freedom from harm, while Quality means the correct treatment is provided at the correct time to the correct patient. Although they may have different definitions, the two topics are inextricably linked, and the medical community should address Safety and Quality issues.

Robert Haskins (rhaskins@healthcareteamtraining.com) is CEO of Healthcare Team Training, LLC, and has over 20 years of CRM experience as an airline captain with a major commercial carrier, and graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis with a degree in engineering. He is a former Naval aviator, former military and current airline instructor pilot, and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) aircrew program designee. He has over 6000 CRM instructional hours and over 9000 flight hours on various military and civilian aircraft.

S. Wayne Sanders (wsanders@healthcareteamtraining.com) is a co-founder and executive vice president of Healthcare Team Training, LLC. He holds a bachelor of science degree in insurance and risk management from Georgia State University and is a licensed insurance broker. He is the risk management consultant for The Institute of WorkComp Advisors headquartered in Asheville, North Carolina. Wayne was the principal for 13 years of Pure Risk Solutions, LLC (PRS) a risk management consulting practice he founded. For 11 years prior to PRS, he was the regional risk manager of a Fortune 500 company.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2001, March). Reducing and preventing adverse drug events to decrease hospital costs. Research in Action, Issue 1. AHRQ Publication Number 01-0020. Rockville, MD: Author. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/aderia/aderia.htm

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2004, May3). Beyond blame: Ob-gyns investigating model reforms on patient safety. Press Release. http://www.acog.org/

from_home/publications/press_releases/nr05-03-04.cfm

American College of Surgeons. (2004, October 14). Will aviation fly in the OR? Clinical Congress News. http://www.facs.org/clincon2004/pressinfo/ccnews04day4.pdf

Endsley, M. (1994). Situational awareness in aviation systems. In D.J. Garland, et al. (Ed.), Handbook of Aviation Human Factors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assocs.

Garrison, R. H., & Noreen, E. W. (2003). Managerial accounting. New York:McGraw-Hill, 6369.

Gelinas, L., et al. (2002). The business case for retention. Journal of Clinical Systems Management, 4(78), 1416, 22.

Helmreich, R., et al. (2001). Applying aviation safety initiatives to medicine. Focus on Patient Safety, National Patient Safety Foundation 4(1). http://www.npsf.org/download/Focus2001Vol4No1.pdf

Helmreich, R., et al. (1999). The evolution of crew resource management training in commercial aviation. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 9(1), 19-32. http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/group/

HelmreichLAB/Publications/pubfiles/Pub235.pdf

Helmriech, R. et al. (1993). Why crew resource management? Empirical and theoretical bases of human factors training in aviation. In E. L. Weiner, et al., (Eds.) Cockpit Resource Management. New York: Academic Press.

Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: ÝNational Academy Press. http://www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/4/117/0.pdf

Kuhn, A., et al. (2002). The need for risk management to evolve to assure a culture of safety. Quality and Safety in Health Care 11, 158162. http://qhc.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/11/2/158

Lazarou, J. (2003, July 21) Changing the focus of traditional ’rounds’ improves patient care. The Gazette Online 32(40). http://www.jhu.edu/~gazette/2003/21jul03/21rounds.html

Morey, J., et al. (2002). Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training. American College of healthcare Executives. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m4149/is_6_37/

ai_97177046/print

Musson, D., et al. (2004). Team training and resource management in healthcare: Current issues and future directions. Harvard Health Policy Review 5(1), 25-35. http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/homepage/group/

HelmreichLAB/Publications/pubfiles/musson_helmreich_HHPR_2004.pdf

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). (2002, April). The factors fueling rising healthcare costs. Washington, DC.: American Association of Health Plans. http://www.aahp.org/InternalLinks/

PwCFinalReport.pdf

Sexton, J., et al. (2000). Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. British Medical Journal 320, 745-747. http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/

content/full/320/7237/745

Shapiro, M., et al. (2004). Simulation based teamwork training for emergency department staff: Does it improve clinical team performance when added to an existing didactic teamwork curriculum? Quality & Safety in Health Care 13, 417421. http://qhc.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/13/6/417

Singer, S., et al. (2003). The culture of safety: Results of an organization-wide survey in 15 California hospitals. Quality & Safety in Health Care 12, 112-118.