Community Hospital Gives Its Discharge Process a BOOST

July/August 2013

![]()

Community Hospital Gives Its Discharge Process a BOOST

The nation’s healthcare system recognizes the need to improve the coordination of care transitions (hand-overs) between healthcare providers (Bisognanao & Boutwell, 2009; California HealthCare Foundation, 2008). Emerging entities such as transition clinics, transitional nurses, medical homes, and accountable care organizations are examples of the healthcare system striving to improve care coordination.

The nation’s healthcare system recognizes the need to improve the coordination of care transitions (hand-overs) between healthcare providers (Bisognanao & Boutwell, 2009; California HealthCare Foundation, 2008). Emerging entities such as transition clinics, transitional nurses, medical homes, and accountable care organizations are examples of the healthcare system striving to improve care coordination.

For hospitals, much of the need for improved transitions centers around the discharge process. Many healthcare providers agree the current hospital discharge process is broken (Coleman & Berenson, 2004). Roger Resar, MD, observes, “Hospital discharge is random events connected to highly variable actions with only a remote possibility of meeting implied expectations” (2006).

Today, hospitals are seeking reliable strategies to improve the broken and fragmented discharge process. Historically, the movement of research into widespread clinical practice is extremely slow (AHRQ, 2004). More reports “from the field” demonstrating the application of research-based models in daily practice may spur more rapid adoption of practice improvements. This article describes St. Francis Hospital’s (SFH) participation in Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), an evidence-based improvement model for care transitions (SHM, 2010).

Project BOOST: An Overview

Project BOOST is a national improvement initiative led by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). SHM represents more than 10,000 hospitalists and is committed to enhancing the practice of hospital medicine by promoting education, research, and advocacy. Project BOOST was created by SHM with the support of the John A. Hartford Foundation and uses evidence-based principles to improve hospital discharges and patient transitions (SHM, 2010).

Project BOOST is a 1-year program that incorporates a research-based toolkit of interventions along with an expert physician mentor to improve patient care transitions. Since its inception, more than 100 hospitals have participated in the BOOST program.

St. Francis Hospital: An Overview

St. Francis Hospital is a 130-bed acute care community hospital located in the Puget Sound region of Washington state. The hospital is a member of a faith-based, regional, five-hospital system, Franciscan Health System (FHS). FHS is a member of the Catholic Health Initiatives healthcare system.

|

• The Affordable Care Act focuses on decreasing avoidable hospital readmissions. Beginning in 2013, hospitals with higher than expected readmission rates experience decreased payments for Medicare discharges. The Medicare Patient Advisory Commission (MedPac) estimates that a $12 billion savings related to potential avoidable readmissions could be achieved by improving the quality of patient discharge/transition and coordination of the healthcare team (California HealthCare Foundation, 2008; MedPac, 2007). |

The hospital has a physician hospitalist service, which admits and manages care for the majority of acute care patients 24/7. The Critical Care unit also has intensivist coverage 24/7. Community primary care physicians do not admit or care for patients in the hospital.

Patients admitted to St. Francis Hospital are cared for on a 28-bed medical telemetry unit, 28-bed medical surgical unit, or a 30-bed critical care unit with combined intensive care (ICU) and step-up/step-down progressive care (PCU).

The nursing care delivery model, called Practice Partner, is directed by a registered nurse. On medical surgical and telemetry units, there is an average 1:5 nurse-patient ratio, and a shared nursing assistant between two registered nurses. Care delivery is supported by a multidisciplinary team that includes nurse educators, nurse care managers, social workers, pharmacists, therapy services, pastoral care, and palliative care.

Rationale for Participation in Project BOOST

St. Francis Hospital leadership sought to participate in Project BOOST because it was a structured, research-based, and mentored quality improvement program focused on care transitions. Outcome measures indicated a need for improvement related to overall length of stay and readmission rates. Also, patients with heart failure were a population requiring more intensive intervention.

Self-Assessment: Factors Supporting Successful Launch

The first step of Project BOOST was to complete a comprehensive self-assessment. The exercise addressed current medical and nursing committees and the systems necessary for successful implementation. This valuable self-assessment can help hospital leaders decide if their facility has the foundation and resources needed to undertake a year-long improvement project:

- Senior executive leadership was willing to commit the time and financial resources necessary to launch and sustain Project BOOST.

- Discharge and transition processes required improvement.

- Data: Ability to obtain baseline quality measurements and provide ongoing reporting via computerized data management.

- Existing medical and nursing committees with the capacity and skill to implement interventions.

- Availability of two comparable units, one to serve as the interventional BOOST unit, and one to serve as a control unit. The majority of the targeted medical patient population, including heart failure patients, receive care on one of two units. At St. Francis, the BOOST unit was the medical telemetry unit, and the designated control unit was the PCU.

Project BOOST Participation

Planning Phase: November 2011 to February 2012

St. Francis Hospital, along with eight other hospitals from across the nation, was selected by the SHM to be a participant in the 2011–2012 Project BOOST cohort. Teams attended a 2-day kick-off in October 2011 to receive education on BOOST interventions and meet with their assigned physician mentor for the project.

After returning from the kick-off, conference attendees met to create an operational structure to guide the next year’s work. Three important components were developed:

- an Executive Steering Committee, in addition to the multidisciplinary BOOST Steering Committee,

- an action and communication plan, and

- a data dashboard to display BOOST targets and outcomes. The BOOST dashboard served as a concise visual report that was widely shared throughout the course of the project.

The Executive Steering Committee closely followed the improvement methodology outlined in the Project BOOST Implementation Guide (SHM, 2010). The BOOST program encourages participants to approach improvement work in timed phases: Planning phase (1 to 3 months); Implementation phase (4 to 6 months); Intervention phase (6 to 9 months); and Project surveillance and management (1 year and ongoing). Along with the guidance of the Executive Steering Committee and SFH BOOST mentor, these phases provided ongoing milestones and benchmarks for the team’s work.

Project Boost Executive Steering Team

The Executive Steering Team served as the local leaders of Project BOOST and was comprised of the four kick-off attendees. A hospitalist medical director and adult health clinical nurse specialist served as BOOST co-leaders. An RN care manager was an expert clinical leader and an RN acute care director served as Project BOOST facilitator. The Executive Steering Team met every 2 weeks for ongoing “check and adjustment.” This team also served as the primary point of contact for the SFH BOOST Steering Team, Franciscan Health System, as well as the national BOOST cohort.

Along with their Project BOOST mentor, the Executive Steering Team addressed short-term and long-term goals, baseline data collection, and defined outcome measures of success.

Long-Term Aim for Project BOOST

The overarching goal of St. Francis Hospital’s participation in Project BOOST was to improve care transition processes from hospital admission through discharge. Focusing BOOST interventions on a single unit, the defined objective for the project was to improve and sustain high quality, safe, cost-effective care transitions for patients by October 2012.

Short-Term Aims for Project BOOST

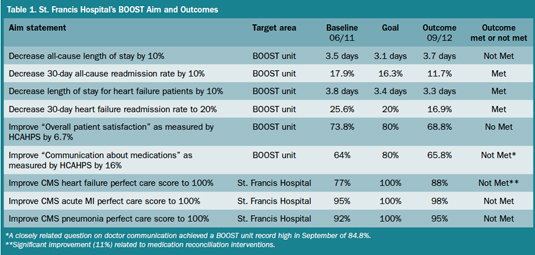

Throughout November and December, short-term aim statements and outcome metrics were established to track ongoing BOOST progress (Table 1). Developing a process for obtaining and submitting the required monthly statistics for the national BOOST database required a significant amount of time. Submitted data included patient satisfaction scores (HCAHPS), length-of-stay data, and readmission rates.

Aim statements were developed based upon the need for improvement in several Medicare core measure metrics and patient satisfaction scores. The Executive Steering Team supported an initial focus of Project BOOST interventions on improving the care of heart failure patients, ultimately with the objective of transferring and spreading many of the practice improvements to other patient populations.

Click here to view a larger version in a separate window.

Project BOOST Steering Committee

Multidisciplinary team members—a nurse manager, educator, frontline staff, physicians, social worker, and pharmacist—were chosen for their clinical expertise and ability to lead change. The BOOST Steering Committee met every 2 weeks with administrative support and facilitation by the team’s clinical nurse specialist. The steering committee was the “glue” for the project. Each member was expected to commit to the team’s action and intervention implementation plan on the Project BOOST unit for the duration of the project.

Steering Committee members kicked off their participation in Project BOOST in November. In addition to teaching Steering Committee members about BOOST and the objectives for the project, the team reviewed data and began a process map of the current state on the BOOST unit. The process map was studied and refined over the next 6 weeks in order to assist the team with prioritizing opportunities for improvement. Process mapping is a tool recommended by Project BOOST for problem identification and clarification (SHM, 2010).

Implementation and Intervention Phase: March to August 2012

A Project BOOST kick-off for community primary care providers resulted in the first BOOST intervention at St. Francis: a redesigned discharge summary template. The template was designed with input from primary care providers to include critical information necessary for them to safely and efficiently assume care after discharge in the outpatient setting.

Initially, the BOOST Steering Committee had to prioritize the comprehensive problem list generated through process mapping and hazard analysis scoring. The team determined which problems and interventions would make the most significant overall impact on achieving the both the short- and long-term BOOST goals. Use of PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Adjust) cycles and small tests of change were invaluable in the team’s ability to refine and change interventions without total reinvention or elimination of a process. The team was guided in conducting small tests of change without the expectation to “have it right” upon first implementation of a new intervention. Intervention trials were conducted on a small scale to include one doctor and one nurse on one shift, with revisions or abandonment occurring quickly.

|

|

| BOOST Executive Steering Committee members at St. Francis Hospital. Front row (l to r): Dr. Vidya Menon, associate medical director; Pam Cronrath, MN, RN, (former) acute care director. Back row (l to r): Sharon Ramos, RN, care manager; Marisa Gillaspie Aziz, RN, MSN, ACNS-BC, clinical nurse specialist |

Initial interventions targeting heart failure patients focused on early and accurate identification, essentially defining who the heart failure patients were. Problems with identification were addressed through standardization of the daily morning multidisciplinary huddle. During the morning huddle, all hospitalists present standardized information for each of their patients, including diagnosis and heart failure identification, as well as care planning information. A table-tent guide was developed as a reference tool and prompt for the hospitalist team, and all huddle attendees were encouraged to assist physicians in using the guide.

Often a single BOOST intervention would naturally segue into another intervention. For example, improved heart failure patient identification led to efforts targeting the long-standing problem of inaccurate medication reconciliation at discharge. A joint intervention including nursing and the pharmacy was initiated to improve medication reconciliation accuracy. The team began to conduct a “2nd-eye review” of discharge medications for heart failure patients. This collaborative review process is credited with the improvement in medication reconciliation scores.

Another opportunity we identified for improved transition planning was to implement screening for readmission risk upon admission. Literature reports that certain risk factors, such as polypharmacy, depression, lack of support, and chronic disease, are associated with increased readmissions (Bisognanao & Boutwell, 2009; SHM, 2010). Screening for readmission risk from the beginning of the hospital stay increases the time available to develop and implement the often complex plans that will be required for a safe discharge. Care coordination needs, including mental health, disease specific follow-up (i.e. heart failure, Coumadin clinic), home medical equipment, transportation, and prescription assistance, must be addressed prior to discharge to ensure patients are successful upon leaving the hospital. The BOOST committees had extensive discussion about the timely and reliable assessment of patients’ readmission risk. The BOOST toolkit included a concise risk screening tool know as the 8P (SHM, 2010). After much debate, it was decided that in order to optimize communication and care coordination, the best time for 8P risk screening was during daily MD/RN patient rounds. Joint rounds provides the opportunity for the care team to review the patient’s risk for readmission using the 8P tool and plan accordingly for appropriate, patient specific interventions.

Throughout the implementation and intervention phases, the expertise of the SFH Project BOOST physician mentor was a valuable improvement resource. Conference calls were scheduled with the team’s BOOST mentor every other month to review and discuss intervention challenges. Additionally, a midpoint 2-day on-site visit by the BOOST mentor provided an infusion of improvement expertise and insight.

Review of Major BOOST Interventions Impacting Practice

During the implementation and intervention phases, there were three BOOST interventions that impacted both nursing and physician workflow. Because these types of personal practice changes can be threatening, the success of these interventions required several months of open discussion with care team members. Many means and methods of communication were needed to garner support for significant practice changes. Discussions at staff meetings were open, transparent, and at times conflicted. It was helpful for the Executive Steering Committee leaders to discuss and recognize that patience and time is required for personal practice changes to be successful.

1. Daily MD/RN patient rounding.

Both physicians and nurses were conceptually supportive of the value of daily MD/RN rounding for patient satisfaction, team communication, and overall quality of care (California HealthCare Foundation, 2008; Dailey, Loeb, & Peterman, 2007; Katz, 2008a). However, to gain their support, several processes and role responsibilities needed to be developed and agreed upon. First, a process was developed to facilitate the scheduling of rounds. The new process used Vocera (wireless voice technology) to schedule the rounding visit between the provider and RN. Another step was to define the content discussed during the visit with the patient. After several revisions, a template outlining standardized rounding roles and content was implemented. Initial MD/RN rounding was trialed with heart failure patients and has now spread to all patients on the Project BOOST unit. A structured communication template is used by both the doctor and nurse to support an efficient and high quality bedside round with the patient.

2. Teach Back for patient education.

Teach Back is a recommended and research-based BOOST intervention (SHM, 2010). It is estimated that 49% of hospitalized patients experience at least one error related to complex discharge instructions, medication regimen, or diagnostics (AHRQ, 2004). One study reported only 41.9% discharged patients could state their diagnosis and only 27.9% could list all of their medications (Axon, 2012). These outcomes support the need for a different and non-traditional patient education program.

Teach Back is based on an assessment of the patient’s ability to recall or demonstrate changes in treatment or medications through the use of open-ended questions. The Teach Back process is simple and brief in concept; however, for clinicians to become proficient with Teach Back, they must practice incorporating this skill set into their own patient education repertoire (Gibson, Kornburger, & Sadowski, 2010)

Appreciating the value of Teach Back for all patients, the BOOST Executive Steering Committee ultimately decided to make Teach Back the standard practice for all patient education. Nursing, physician, and pharmacy staff participated in a formal Teach Back training including a lecture, Teach Back video (a Project BOOST tool), and interactive role-playing exercises focused on development of the Teach Back skill set.

3. Geographic hospitalist assignments.

With geographic assignments, a hospitalist is assigned to a defined geographically located unit, rather than having patient assignments on multiple units. Geographic assignments have been shown to facilitate more timely and accurate communication between clinicians (Katz, 2008b). At St. Francis, geographic assignments were briefly implemented in February 2012, and then put on hold within a month due to the strong physician resistance. In July 2012, after the Project BOOST mentor’s presentation, more group discussions, and scheduling revisions, geographic assignments were successfully resumed.

Intervention Refinement Phase: September to October 2012

Executive Steering Committee members unanimously agreed that during the last phase of Project BOOST, no new interventions would be implemented. Instead, the team would focus their efforts reinforcing and hardwiring interventions implemented over the prior 6 months.

Steering Committee members were guided in developing strategies for refining processes and tools used in current interventions. For example, the scripted template for MD/RN rounding was modified to include the 8P risk assessment.

Results

Overall, the outcomes achieved through SFH’s participation in Project BOOST reflect improved chronic disease management on the BOOST unit (Table 1). The goals for 30-day all-cause readmission rates and heart failure were met with only a modest increase in overall length of stay for both populations. MedPac reports a 30-day all-cause national average readmission rate of 17.6% (2007), compared with the BOOST unit final month (9/2012) outcome of 11.2%.

Also of note, the CMS heart failure perfect-care score, while not reaching the target of 100%, increased by 17% to 87%. This is a record high for this measure at SFH. This achievement can be attributed to the successful implementation of Project BOOST interventions targeting care team communication and medication reconciliation accuracy.

It is important to note that throughout the project, data was tracked as recommended on the PCU (BOOST control unit). However, as the project progressed, it became apparent that some BOOST interventions had inadvertently spread between the BOOST unit (medical telemetry) and the control unit (PCU). This unintentional spreading was likely related to the small size of the hospital, with both nurses and physicians working both the BOOST unit and control unit throughout the duration of the project. In summary, the PCU did not function as a control unit during this project.

Discussion

St. Francis’ leadership elected to apply for participation in Project BOOST at a time when the hospital was struggling with how to move forward with improved care coordination and transition for patients. For St. Francis Hospital, the Project BOOST collaborative provided the structure and expert resources for initiating and sustaining improvement initiatives. The research-based toolkit and physician mentorship were critical factors in the successful implementation of Project BOOST at SFH.

Beyond official participation in the Project BOOST cohort, St. Francis leadership has identified several areas of ongoing work:

- Continued improvement of medication reconciliation accuracy.

- Further spread and reinforcement of standardized MD/RN rounding.

- Improved transitions and hand-overs to primary care, skilled nursing, and community health agencies.

- Reliable scheduling of follow-up appointments prior to discharge for high-risk patients.

- Increased caregiver and family involvement with transitions.

- Onboarding of new clinicians regarding BOOST processes.

- Reinforce patient education using standardized resources and Teach Back.

- Explore new healthcare roles designed to help bridge transition care across the continuum.

- Maintain a data dashboard for ongoing outcomes tracking and sharing.

Conclusion

St. Francis Hospital’s participation in a year-long program, Project BOOST, guided the prioritization and design of often complex opportunities for improvement in communication, care coordination, and discharge. Many research-based quality improvement processes such as process mapping, hazard analysis, PDCA, and data dashboards, were utilized to facilitate decision making along the way. Ongoing measurement and reporting of process measures and outcomes to stakeholders was important to maintaining project visibility, energy, and commitment to improvement.

Pam Cronrath is the former director of acute care services at St. Francis Hospital. She is now working for Soyring Consulting as a consultant and may be contacted at rat.bugs@gmail.com.

Marisa Gillaspie Aziz, is a clinical nurse specialist at St. Francis Hospital in Federal Way, Washington. She may be contacted at marisagillaspie@fhshealth.org.

References

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to recognize Nancy Brown for her outstanding support of the SFH BOOST team and her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.