Clinical Analytics

January/February 2011

Clinical Analytics

EMR Implementation Is an Opportunity, Not a Guarantee

As hospital IT leaders consider how to address meaningful use of electronic medical records (EMR) within their own organizations, they should see the next generation of EMRs as an opportunity to take arms against avoidable medical errors, improve the level of personalized medicine, and reduce hospital readmissions to boost quality scores.

As a medical professional, I made the deliberate choice more than a decade ago to lasso the power of clinical data to improve outcomes, and I am thrilled about the incentives for adopting EMRs. The wealth of clinical data they will produce can be harvested, analyzed, and used to drive new best practices at the point of care.

However, the implementation of EMRs alone will not increase the amount of actionable health intelligence. Instead, EMR vendors will have to look beyond the hurdles of data interoperability to realize the potential to generate new insights that will help solve major patient care challenges. Below are a few examples.

Creating sophisticated and accurate active problem and medication lists. The meaningful use of EMRs requires the maintenance of up-to-date patient problem and medication lists, also known as active problem and active medication lists. The use of these lists can put the patient’s current episode in appropriate context.

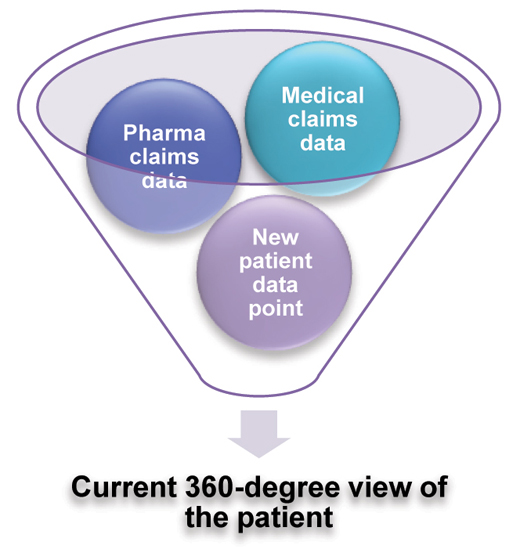

That’s a good first step. But without more information, adding a new diagnosis or procedure may just add to a cluttered list. Analyzing clinical data from an EMR that is connected with a patient’s unique medical history, whether comprised of health plan or pharma claim data or a personal health record kept by the patient, can net highly accurate, more intelligent lists with diagnoses prioritized for severity, and medications evaluated for formulary, co-pay, safety, and a host of other variables (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Connect clinical data from the EMR with data from other sources to create an up-to-date 360-degree view of the patient.

All of this leads to a more highly personalized base of knowledge from which to treat the patient, which is likely to lead to better outcomes, both in the short and long term.

Using data to fight medical errors and prevent CMS Never Events. Medical errors, such as administering medications carrying potential for known adverse reactions, are largely avoidable if patient data is captured and considered at the point of care. Integrating an analytics function within the EMR facilitates the use of a patient’s unique medical history for safer prescribing.

There is a tendency to look at predictive analytics as a tool for population analysis rather than targeting the individual patient, but both are effective means of identifying potential health problems and preventing them before they occur. Using clinical data to identify populations at risk for chronic conditions is generally the domain of the payer community, but more and more, providers can leverage this data to get a better understanding of their admitted populations to intervene on risk for such things as CMS Never Events.

Analyzing a hospital’s EMR data to identify patients admitted for procedures that may affect their mobility is one example. An analysis can produce a prioritized list of patients who may be at risk for the CMS Never Event categorized as a fall. This kind of analysis may be a function within the EMR and analysis may be automatic each time a new patient data point is entered. If, for example, a patient recovering from a hip replacement is prescribed a sleeping aid such as a long-acting benzodiazepine, that may further increase the patient’s risk for a fall, and that bed may rise to a higher priority on the at-risk report, targeting increased monitoring or other precautions.

Bridging the gap between patient, provider, and payer to prevent hospital readmissions. Whether it’s within the first 30 hours or 30 days following discharge, the likelihood of a patient being readmitted drops significantly if a bridge is built between the healthcare provider and the payer’s care management system.

The payer may only become aware of a new and serious diagnosis or condition as the result of filed claims, which may take 30 to 60 days. This is a critical time for the payer to be monitoring cross-provider adherence to treatment, and intervening if the patient is not compliant. If the payer has rapid access to the patient’s most current clinical data upon discharge revealing a new diagnosis or condition, a personalized care management program can be created immediately to promote recovery, foster education, and prevent another episode requiring urgent care or hospitalization.

Overcoming operational challenges. The efficient and effective analysis of EMR data to improve outcomes and lower clinical costs does have its own set of hurdles.

- Accurate data. Because data is entered by humans, human error cannot be eradicated, but analytics tools within an EMR can detect errors as they are made to minimize the human factor. For example, if a record indicates a patient is male, then an ICD code indicating a hysterectomy could produce an immediate alert questioning the code entered, and offering an opportunity to correct it.

- Obtaining data from disparate sources. Hospital CMIOs often lament the lack of discrete clinical data beyond what their own physicians enter. Lab values, for example, are a critical element of producing that 360-degree view of a patient, but obtaining and integrating that data with the EMR is perceived as a difficult task. Newer, sophisticated EMRs can take in lab values and incorporate them into the patient record for a more comprehensive view of the patient’s condition.

- Data interoperability. Different codes are different technical languages. Some EMRs have solved the problem of code-based data by creating crosswalks to a common computable language.

- Designing the analysis. Now that rich clinical data is available, the provider can use it to go far beyond just fulfilling the requirements of Meaningful Use. Defining objectives for clinical data analysis starts by aligning with the overall organizational objectives and identifying problems that can be solved by having a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of your patients’ health, both as a group and as individuals.

- Who is at risk for Never Events?

- Who is at risk for a near-term hospital readmission?

- Who is at risk for non-adherence?

Healthcare is entering its information age with the adoption of electronic medical records. The connections that digitized clinical data enables open new doors to understanding the true health of a patient.

Your choice of electronic medical records is a critical one, and the analytics that are provided by your EMR choice should be an important part of the decision criteria.

Ahmed Ghouri is co-founder of Anvita Health, a board-certified anesthesiologist, and principal author of 70 scientific publications. As chief medical officer for Anvita, he oversees all clinical informatics and serves as Anvita’s liaison to the medical community. Ghouri served as co-investigator on the Phase III trials for FDA-approved pharmaceutical products flumazenil (Romazicon) and desflurane (Suprane). He served as an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, and held an attending anesthesiologist position at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Beverly Hills, California. He received a medical degree from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, where he also completed a biomedical engineering research fellowship. Ghouri may be contacted at ahmed@anvitahealth.com.