Call to Action: Long-Standing Strategies to Prevent Accidental Daily Methotrexate Dosing Must Be Implemented

By the Institute for Safe Medication Practices

Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist that was originally approved to treat a variety of cancers. Used for oncologic indications, methotrexate is administered in cyclical frequencies and in variable doses based on body surface area and the type of cancer being treated—for example, 12 g/m2 per dose when treating osteosarcoma. The labeled indications for methotrexate later expanded to include the treatment of nononcologic conditions, including psoriasis (approved in 1971) and rheumatoid arthritis (approved in 1988). Other nononcologic off-label uses include the treatment of Crohn’s disease, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory myositis, reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome), graft-versus-host disease, Takayasu arteritis, uveitis, and ectopic pregnancy. For most nononcologic indications, a low dose of methotrexate is administered just once or twice weekly—for example, 7.5 mg per week when treating rheumatoid arthritis.

Relatively few medications are dosed weekly; thus, accidental daily dosing of oral methotrexate has occurred all too frequently. This type of wrong-frequency error has originated in all stages of the medication use process, from prescribing to self-administration. These errors have resulted in serious methotrexate overdoses that led to vomiting, mouth sores, stomatitis, serious skin lesions, liver failure, renal failure, severe myelosuppression, gastrointestinal bleeding, life-threatening pulmonary symptoms, and, in some cases, death.

Since early 1996, harmful or fatal errors with daily oral methotrexate for nononcologic use have been reported to ISMP and published in more than 60 of our ISMP Medication Safety Alert! newsletters. Thus, oral methotrexate for nononcologic use has been included on the ISMP List of High-Alert Medications (www.ismp.org/node/103) since the inception of the list in 2003. Although the risk of errors with oral methotrexate for nononcologic use has been known for a long time, harmful and fatal errors are still occurring today. Descriptions of recently reported events follow.

Methotrexate errors

Medication reconciliation and transition-in-care error

The most recent event involved an error that was caught during hospitalization but continued upon discharge when an incorrect entry for daily methotrexate on a patient’s home medication list was not corrected. An elderly man with rheumatoid arthritis was admitted to a hospital with renal failure. At home, he had been taking oral methotrexate 2.5 mg twice weekly (Mondays and Wednesdays). The admitting nurse began creating a list of the patient’s home medications. The admitting physician noticed that methotrexate was missing from the home medication list in the patient’s electronic health record and added it. However, he mistakenly documented that the patient had been taking 2.5 mg of oral methotrexate twice daily instead of twice weekly. He then made this an active order during the patient’s hospitalization.

Noticing the daily order for methotrexate, a pharmacist in the central pharmacy contacted the physician to let him know that he must prescribe daily methotrexate on a hospital-mandated chemotherapy order template. However, the pharmacist did not verify that the patient had an appropriate oncologic indication for the order. The physician simply complied with the pharmacist’s request and prescribed the daily methotrexate via a chemotherapy order template. Fortunately, an oncology pharmacist identified the error after talking to the patient and corrected the active order, changing the dose from twice daily to twice weekly. However, it never crossed his mind to correct the methotrexate entry on the patient’s home medication list.

The patient received the correct dose—one 2.5 mg tablet—of methotrexate on Wednesday during his five-day hospital stay before being transferred to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Upon discharge, the physician reconciled the patient’s list of home medications for continuation upon discharge. In doing so, he pulled the erroneous methotrexate entry over to the list of medications to continue upon discharge, thus prescribing oral methotrexate 2.5 mg twice daily for the patient while at the SNF. The patient received twice-daily methotrexate for more than a week before he was rehospitalized with a change in mental status, severe neutropenia, and mucositis. Sadly, he never recovered and died in the hospital about a week later.

Misunderstood instructions

Another recent error involved a correctly filled outpatient prescription for weekly methotrexate with an escalating dose change two weeks later. Unfortunately, the patient misunderstood the instructions on the label and took the medication daily. An eight-week supply of 2.5 mg tablets (30 tablets) had been dispensed with label instructions that said, “Take 3 tablets by mouth one day for 2 weeks then increase to 4 tablets by mouth 1 day per week thereafter.” Despite counseling, the patient was confused by the label instructions and took three tablets (7.5 mg) daily for five days before serious symptoms led his doctor to identify the error.

Overall complexity with titrated methotrexate doses or divided weekly doses has previously caused confusion. For example, in 2017, a patient with rheumatoid arthritis was hospitalized after mistakenly taking methotrexate three tablets twice a day for four days instead of three tablets in the morning and three tablets in the evening once per week. The prescription label said, “Take 6 tablets by mouth weekly. Take 3 tablets in AM and 3 tablets in PM.” In the labeling for methotrexate, single oral doses of 7.5 mg once weekly are recommended for initial treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. However, divided oral doses of 2.5 mg at 12-hour intervals for three doses, given as a course once weekly, are also recommended. It appears that the use of divided doses has added to patient confusion.

Look-alike, sound-alike issues

Some of the recently reported errors have also involved accidentally selecting methotrexate instead of the intended diuretic metOLazone. Both drug names start with “m-e-t” and have overlapping tablet strengths of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg. In one case, a pharmacy technician who was entering a telephone prescription for oral metOLazone 2.5 mg daily accidentally selected methotrexate 2.5 mg daily. She had searched for metOLazone using the first three letters of the drug name and the strength and selected methotrexate 2.5 mg by mistake since it met both criteria. The computer system did not flag the methotrexate order to require verification of an appropriate oncologic indication since the dosing frequency was daily. The medication was dispensed without the pharmacist noticing the error. The patient’s husband picked up the medication and was asked if he had any questions. When he had no questions, counseling was not provided. The patient took methotrexate 2.5 mg daily as directed on the label and died less than a month later. Mix-ups between these two medications have been previously reported by ISMP.

Assessment of best practices

To prevent accidental daily dosing of oral methotrexate, ISMP has long recommended defaulting computer order entry systems to a weekly dosing regimen, requiring pharmacist verification of an appropriate oncologic indication for daily dosing of methotrexate, and educating patients about the weekly dosing regimen. These best practices have also been on the national to-do list with the ISMP Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals since 2014 (see best practice #2 [a, b, c] at www.ismp.org/node/160).

Although implementation of these best practices has been rising since 2014 (www.ismp.org/ext/69), the most recent data (Table 1) from the ISMP Medication Safety Self Assessment® for High-Alert Medications demonstrate opportunities to improve implementation of these and other best practices that could prevent errors with methotrexate in many hospitals. In the recent self assessment, methotrexate for nononcologic use scored lowest among the 11 high-alert medications included in the assessment. For the 501 U.S. hospitals that submitted data to ISMP for this medication, a mean percent score of only 50% was achieved. Participating hospitals scored particularly low on defaulting to a weekly dosing regimen with computer order entry systems, requiring verification of an appropriate oncologic indication for daily dosing of methotrexate, educating patients about the weekly dosing regimen, prescribing the medication in quantities that do not exceed a 30-day supply, and verifying that all lists and instructions provide the correct dosing instructions.

One of the barriers to defaulting to a weekly dosing regimen with computer order entry systems appears to be that some systems present common orders for oral methotrexate in both daily and weekly dosing frequencies, without an option to edit the display of these orders. When searching for the intended drug, a clinician may pick the first choice that matches the desired dose, without noticing that the frequency of administration listed is daily, not weekly.

Recommendations

Ongoing errors with oral methotrexate for nononcologic use suggest that more needs to be done to reduce the risk of patient harm. Most of the wrong-frequency and wrong-drug errors with methotrexate could be prevented by fully implementing the Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices associated with methotrexate and other related risk-reduction strategies in the ISMP Medication Safety Self Assessment® for High-Alert Medications, including:

> Defaulting to a weekly dosing schedule in prescriber and pharmacy order entry systems

> Requiring verification and entry of an appropriate oncologic indication in order entry systems for daily orders

> Educating patients and providing them with verbal and written instructions that specify the weekly dosing schedule and emphasize the danger with taking daily or extra doses

> Asking patients to repeat back the instructions for taking oral methotrexate to validate understanding

> Verifying the dose and frequency of all medication lists and discharge instructions

> Limiting the prescription quantity to a 30-day supply (e.g., dispensing just eight 2.5 mg tablets for a 5 mg weekly dose would reduce the risk of a serious overdose)

Other important risk-reduction strategies for clinicians, technology/drug information vendors, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are provided below.

Clinicians: Medication reconciliation

> Update and edit the patient’s home medication list as needed throughout the patient’s hospitalization so it can accurately guide medication reconciliation.

> Create a daily list of active orders and discharge prescriptions for oral methotrexate generated from the order entry system, and require a pharmacist to review the orders and prescriptions to verify the dose and frequency based on the patient’s diagnosis.

Clinicians: Prescribing

> Provide clear directions on oral methotrexate prescriptions. Avoid “take as directed” instructions, include the strength and dose in mg, provide clear instructions for weekly dosing, and limit the number of tablets to a four-week (30-day) supply.

Clinicians: Dispensing

> Provide clear instructions on pharmacy labels for weekly dosing, and specify the day of the week (written in full, not abbreviated) the medication should be taken. Affix an auxiliary warning label (preferably preprinted) to remind patients that the dose should be taken weekly.

When available and covered by the patient’s insurance, dispense oral methotrexate for nononcologic use in outpatient settings in a dose pack that helps guide patients to take the proper dose weekly. Dispensing loose tablets of methotrexate for nononcologic use in prescription vials is highly discouraged in outpatient pharmacies if methotrexate dose packs are available and covered by the patient’s insurance.

Clinicians: Patient education

> Provide all patients with a copy of the free ISMP high-alert medication consumer leaflet on oral methotrexate (found at www.ismp.org/ext/68).

> When possible, provide the patient with a visual calendar to clarify the weekly dosing schedule.

> If folic acid is prescribed along with methotrexate, educate patients about the differences between the medications and their respective administration schedules (Harrison & Jones, 2014).

> Educate patients about the key symptoms of methotrexate toxicity and to whom to report the symptoms.

Clinicians: Patient monitoring

> If a methotrexate dosing error is discovered, ensure the patient receives immediate medical attention (Howard, McCormick, Pui, Buddington, & Harvey, 2016; Bidaki, Kian, Owliaey, Babaei Zarch, & Feysal, 2017).

Technology/drug information vendors

> Build computer order entry systems to ensure clinicians have access to the functionality needed to prevent methotrexate errors (e.g., default to weekly dosing, hard stop for verification of indication with daily orders).

FDA (which is currently evaluating the need for regulatory action)

> Change and limit the approved dosing regimen to once weekly as a single dose (not divided doses 12 hours apart or twice weekly), if appropriate.

> Encourage manufacturers to package oral methotrexate for nononcologic use in patient dose packs that direct consumers to the correct weekly dosing.

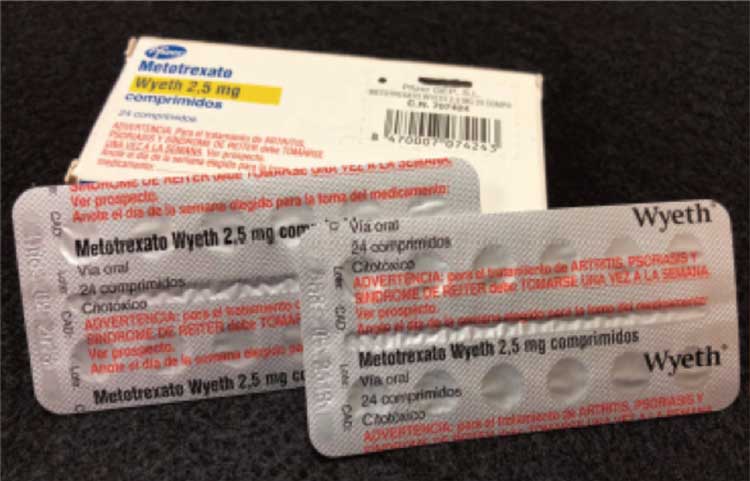

> Require prominent warnings on the packaging of oral methotrexate for nononcologic use about weekly administration, as is done in other countries (Figure 1).

From the August 9, 2018 issue of ISMP Medication Safety Alert!

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2013). Preventing falls in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care (AHRQ Publication No. 13-0015-EF). Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/fallpxtoolkit.pdf

Capone, L. J., Albert, N. M., Bena, J. F., & Tang, A. S. (2013). Serious fall injuries in hospitalized patients with and without cancer. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(1), 52–59. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182679056

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Costs of falls among older adults. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/Falls/fallcost.html

Forneris, S. G., & Peden-McAlpine, C. (2007). Evaluation of a reflective learning intervention to improve critical thinking in novice nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(4), 410–421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04120.x

Hoke, L. M., & Guarracino, D. (2016). Beyond socks, signs, and alarms: A reflective accountability model for fall prevention. American Journal of Nursing, 116(1), 42–47.

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 14(4), 595–621. doi:10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

Mantzoukas, S. (2008). A review of evidence-based practice, nursing research and reflection: Levelling the hierarchy. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17(2), 214–223. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01912.x

Overcash, J., & Beckstead, J. (2008). Predicting falls in older patients using components of a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12(6), 941–949. doi:10.1188/08.CJON.941-949

Spoelstra, S. L., Given, B. A., & Given, C. W. (2012). Fall prevention in hospitals: An integrative review. Clinical Nursing Research, 21(1), 92–112. doi:10.1177/1054773811418106

Stone, C. A., Lawlor, P. G., Savva, G. M., Bennett, K., & Kenny, R. A. (2012). Prospective study of falls and risk factors for falls in adults with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(17), 2183–2133. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7791

Wildes, T. M., Dua, P., Fowler, S. A., Miller, J. P., Carpenter, C. R., Avidan, M. S., & Stark, S. (2015). Systematic review of falls in older adults with cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 6(1), 70–83. doi:10.1016/j.jgo.2014.10.003