Addressing Alarm Problems in the Emergency Department

May/June 2013

![]()

Addressing Alarm Problems in the Emergency Department

Stand for a few moments in the middle of your emergency department (ED) to just listen and observe. How many alarms do you hear? Can you distinguish where each alarm is coming from and whether it’s a physiologic monitor or ventilator or infusion pump alarm? Does each alarm connote the level of urgency needed for the nurse to respond promptly and appropriately? Do you observe nurses scurrying to respond? Or do the alarms perpetuate while no one responds?

Device alarms should provide an effective safety net to alert caregivers to critical changes in patient conditions or safety-related problems with devices. Does this statement hold true in your organization? Do device alarms provide an effective safety net in your ED?

Unfortunately, as many experts agree, there are serious problems with both the design and use of clinical alarms. In fact, ECRI Institute identified alarm hazards as Number 1 in its Top Ten Technology Hazards in 2013. Many medical devices such as physiologic monitors, ventilators, and infusion pumps rely on alarms to help protect patients, but there are times when alarms actually contribute to the occurrence of adverse events. The reality is that alarm events frequently occur, and the consequences of these events are often serious. Alarm events are those accidents waiting to happen, the results of a perfect storm in an error-prone system.

|

Become a Member of EMPSF in June or July and receive a Free Audio CD of the EMPSF Webinar: “Improve Alarm Management – The Time is Now!” Visit www.empsf.org and join today! Contact us at info@empsf.org. |

Most EDs are plagued by a myriad of alarm problems, such as:

Alarm fatigue, in which the staff become overwhelmed by the excessive number of alarms and become desensitized. Contributing factors for alarm fatigue often include:

- Excessive leads-off alarms caused by:

- Poor electrode skin preparation and placement.

- Failure to put bedside monitor in stand-by mode between vital signs spot checks when the monitor is used only for vital signs spot checks rather than continuous monitoring.

- Failure to put the bedside monitor in stand-by mode when the patient is taken off the monitor for transport to radiology for testing.

- Excessive ECG artifact alarms caused by:

- Poor electrode skin preparation and placement.

- Inadequate preventive maintenance or troubleshooting when nuisance alarms occur.

- Unheeded alarms or delayed alarm response further exacerbating the alarm fatigue problem; nurses only scramble when a critical alarm occurs… that is, if they notice it.

- Unsafe approaches to addressing alarm fatigue, leaving patients vulnerable to delayed alarm response and missed alarms:

- Heart rate and pulse oximetry alarm limits are set outside safe ranges in an attempt to reduce the number of alarms.

- Alarm volumes are turned down to an inaudible level.

- Prompt alarm notification is compromised resulting in delayed alarm response and missed alarms. Examples include:

- The architectural layout of the ED makes it difficult to hear device alarms from patients in some rooms (e.g., around the corner at the far end).

- When the census is high, some patients are monitored via stand-alone physiologic monitors that are not networked to the central station. The only alarm notification is the visual or audible alarm emanating from the device itself. Alarm response may be compromised unless a nurse is within visual range or earshot of the stand-alone monitor.

- It is difficult or impossible to hear alarms coming from devices used in isolation rooms (e.g., ventilators, infusion pumps) because the doors are kept closed.

- There are times when no staff members are in the nurses station to see or hear physiologic monitoring alarms emanating from the central stations.

- Processes for alarm notification and response are ineffective, resulting in delayed alarm response. Examples include:

- A nurse is busy with a particular patient and assumes that another nurse will hear the alarms for his/her other patients and respond.

- There is diffuse responsibility for alarm response.

- There are frequent communication breakdowns between staff responsible for alarm notification and response.

- Alarm notification and response protocols are inadequate or non-existent.

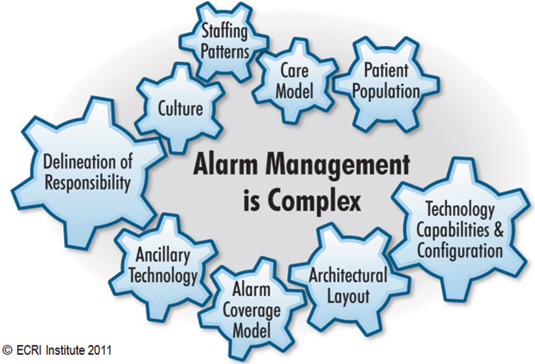

Figure 1: Tailor Improvement Strategies to Your ED’s Unique Context

An Approach for Addressing Alarm Problems and Improving Alarm Management

Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes to address these problems because improving alarm management is a complex issue. Each ED has a unique set of circumstances, unique vulnerabilities, and variations of these common problems. For example, elements such as patient population, clinical needs, staffing patterns, care models, architectural layout, alarm coverage model, and so on, may vary from place to place. Therefore, alarm management strategies must be tailored to be realistically implementable in the context of your ED’s unique circumstances.

Improving alarm management requires a multidisciplinary system’s approach and in-depth process analysis and planning. A multidisciplinary approach provides the following benefits, which are key to the success of improvement efforts:

- Essential input and buy-in from key stakeholders

- In-depth understanding of the problems

- The strength of collaboration

- Support in securing resources

- Shared ownership in the solutions

In-depth analysis and planning require introspectively examining your organization’s culture, infrastructure, practices and technology to identify and address patient safety vulnerabilities and improve alarm management. An effective approach for improving alarm management involves the following elements:

- Assemble a multidisciplinary team. The team should include stakeholders directly and indirectly involved with alarm management. Some essential members include clinicians (including front-line staff), patient safety officer /risk manager, an administrative sponsor, biomedical engineering representative, and IT representative. The team’s ultimate goal should be to improve alarm management and minimize risk. The team should be charged with carrying out the following tasks.

- Review recent events and near misses to identify problem areas or troubling trends that need to be addressed.

- Observe all alarm management processes and ask nurses and other staff about their concerns.

- Review the entire alarm management system (introspective analysis of your organization’s culture, infrastructure, practices and technology).

- Identify patient safety vulnerabilities and potential failures in the alarm management processes.

- Drill down to determine the underlying causes for the patient safety vulnerabilities or potential failures.

- Develop and implement realistic strategies to address underlying causes of patient safety vulnerabilities or potential failures and to mitigate risk.

- Evaluate and monitor the effectiveness of the alarm management strategies.

- Provide feedback to staff and celebrate your success.

Strategies for Improvement

The following examples illustrate alarm management strategies that can be used to address frequent alarm problems in the ED environment. As you read these examples, contemplate:

- Do these problems occur in your ED?

- What are the causes of these problems in your ED?

- How can these strategies be tailored to the unique context of your ED?

Alarm Fatigue

If your ED experiences frequent false alarms due to ECG artifact and frequent leads-off alarms, consider:

Establishing protocols for proper skin preparation and electrode placement.

- Reinforcing the importance of placing monitors in stand-by mode when not in active use (e.g., when patient is taken off bedside monitor for transport, in between vital signs spot checks when monitor is being used only for vital signs spot checks)

- Reinforcing the need to promptly troubleshoot false alarms and leads-off alarms, so they do not continue to reoccur.

The minimal time that it takes for nurses to perform appropriate electrode skin preparation and placement, place monitors in stand-by mode when not in active use, and promptly troubleshoot false alarms and leads-off alarms is well-worth the time investment when you consider the overall time savings. Benefits include preventing alarm fatigue, reducing the number of false alarms and the time that it takes to respond to them, reducing the number of leads-off alarms and the time that it takes to respond to them, reducing staff frustration, and improving patient safety.

Prompt Alarm Notification Is Compromised

If your ED uses stand-alone monitors that are not networked to the central station when the census is high, and it is difficult to hear alarms emanating from them, consider:

- Placing patients who are being monitored via stand-alone monitors closer to nurse’s stations or centers of staff activity to increase the likelihood that alarms will be heard.

- Develop ways to improve patient flow through the ED, so that the need for using the stand-alone monitors is minimized.

- Budget for replacing stand-alone monitors with monitors that are networked to a central station via a wireless network to enhance alarm notification. The monitors could be mounted on roller stands for easy movement to any location.

If your ED has architectural impediments that make it difficult to hear alarms, consider:

- Implementing technology solutions such as remote displays to enhance alarm notification or providing alarm notification to caregivers via pagers or wireless phones.

- Implementing use of a monitor watcher to continuously watch central station displays and provide alarm notification to appropriate staff.

Alarm Notification and Response Processes Are Ineffective

If your ED has ineffective alarm notification and response processes and alarm response is frequently delayed, consider developing/refining alarm notification and response protocols incorporating the following elements:

- Clear delineation of responsibility for alarm notification and for alarm response.

- Tiers of back-up coverage for alarm response.

- An alarm escalation plan, if alarm notification is provided via pager or wireless phone, which specifies who will receive the initial alarm notification and who will receive each subsequent alarm notification as the alarm escalates. An alarm escalation plan also specifies the time interval for each escalation for each type of alarm.

- Communication protocol requirements.

Conclusion

A multidisciplinary systems approach is an effective way to improve alarm management and minimize risk. Improvement strategies must be tailored to be realistically implementable in the context of your ED’s unique circumstances.

Kathryn Pelczarski is the patient safety service line leader for the Applied Solutions Group at ECRI Institute. She has extensive experience in project management related to patient safety, technology assessment, strategic technology planning and visioning, equipment planning, procurement assistance, and utilization studies. She has spear-headed ECRI Institute’s efforts in initiatives such as the Partnership for Patient Care and the Regional Medication Safety Program for Hospitals (regional collaborative programs aimed at strengthening patient safety in hospitals in the Greater Philadelphia area). In addition, she has been instrumental in the development of various ECRI Institute services targeted to improve patient care (e.g., alarm management review, ancillary alarm notification system selection and implementation, bariatric readiness assessment). Pelczarski can be reached at kpelczarski@ecri.org.

References

ECRI Institute. (2012, November). Top ten technology hazards for 2013. Health Devices, 41(11), 32-347.