Navigating Risks in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

By Penny Greenberg, RN, MS; Darrell Ranum, JD, CPHRM; and Dana Siegal, RN, CPHRM

For any woman or man, the diagnosis of breast cancer means having to navigate a very complex healthcare system. In addition to dealing with the emotions of a cancer diagnosis, patients have to rely on the expertise, communication, and empathy of caregivers who practice in environments with inherent risks. To identify these risks and provide insights into potential vulnerabilities for providers and patients, CRICO Strategies and The Doctors Company recently partnered on a detailed analysis of 562 breast cancer medical malpractice claims from 2009 to 2014.

CRICO Strategies and The Doctors Company undertook this analysis knowing that, with the exception of skin cancer, breast cancer remains the most common cancer among American women. It affects approximately one in eight women and is the leading cause of cancer-related death. Additionally, a small number of men are diagnosed with and die from breast cancer yearly. The good news is that the overall rate of newly diagnosed cases began to decrease in 2000, and the overall death rate has continued to trend downward over the past 20 years (A snapshot of breast cancer, 2014).

CRICO, the medical malpractice insurer for the Harvard medical community, and its national division, CRICO Strategies, have built a database of over 300,000 medical malpractice claims from more than 500 hospitals and 165,000 physicians across the United States. Called the Comparative Benchmark System (CBS), this database uses a proprietary coding taxonomy that allows for analysis of inpatient and ambulatory risk in academic and community environments and across all care settings. Claims are submitted from both commercial and captive insurance companies, including The Doctors Company, which, with 77,000 members, is the nation’s largest physician-owned medical malpractice insurer. The Doctors Company conducted its own study of breast cancer claims and agreed to collaborate with CRICO to create a larger data pool. The resulting analysis identified two specific areas where harm occurred:

- During the initial diagnosis, leading to a delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer

- During the management or treatment of breast cancer

Delay in diagnosis

Failure or delay in ordering diagnostic tests, consults, or referrals, as well as failure to have a system in place for communicating the results between providers, can lead to missed or delayed diagnosis. The analysis identified 342 medical malpractice cases where there was a delay in making the diagnosis of breast cancer. Patients alleged that the delay in diagnosis resulted in decreased chance of recovery, decreased life expectancy, or increased recovery time. Of the 342 cases, nearly one-half involved radiology (163 cases, or 48%). The physician office/clinic care setting accounted for 135 cases (39%), most notably family medicine and gynecology.

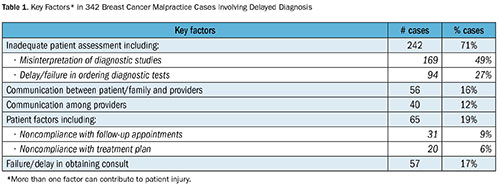

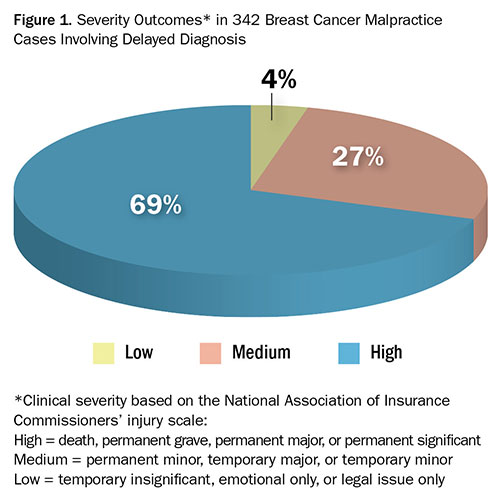

While each case may have multiple contributing factors identified, the most common contributing factor, as determined by expert reviewers, was related to inadequate patient assessment (242 cases, or 71%) (Table 1). Specifically, almost half of these cases (169 cases, or 49%) identified misinterpretation of diagnostic studies as a key driver in the delay. Other assessment issues involved inadequate history and physical, including failure to update relevant family history. An additional  94 cases (27%) included a delay or failure in ordering a diagnostic test. The vast majority of patients who experienced a delayed diagnosis of breast cancer were severely harmed, with 239 cases (69%) resulting in high-severity outcomes (Figure 1)—including 43 deaths.

94 cases (27%) included a delay or failure in ordering a diagnostic test. The vast majority of patients who experienced a delayed diagnosis of breast cancer were severely harmed, with 239 cases (69%) resulting in high-severity outcomes (Figure 1)—including 43 deaths.

The following cases illustrate delayed diagnosis due to multiple failures:

Case 1

A 42-year-old patient arrived for her annual appointment with her gynecologist with the complaint of a self-detected breast lump. The gynecologist ordered a mammogram but did not include the patient’s complaint of the breast lump on the requisition.

The mammogram was read as “normal,” but the report noted “very dense stromal pattern,” which reduces the sensitivity of the study for detection of cancer. The radiologist did not recommend an ultrasound, and the gynecologist received the report read as “normal,” with no recommendation for further testing. In addition, the patient had a positive family history of breast cancer, which was not documen

ted until after her diagnosis.

Allegation: The patient sued the radiologist, alleging that a delayed diagnosis of cancer left her with a poorer prognosis. The gynecologist was not named in the suit.

Key lessons from this case include:

- Soliciting and updating a patient’s family history—especially regarding cancer—is an important part of the clinical history and should always be performed

- Communicating the reasoning behind a referral or test requisition enables the patient and the specialist to assess the nature, importance, and urgency of the request

- Using a breast care management algorithm as a decision support tool is helpful for primary care providers

Case 2

A 32-year-old woman had a breast biopsy and was informed that she had invasive ductal carcinoma. She un

derwent a partial mastectomy. The pathology report indicated that the tissue from surgery was benign. It was later discovered that the patient’s biopsy specimen had been mislabeled: The patient did not have cancer, and the surgery was unnecessary.

Allegation: The patient sued the surgeon for incorrect diagnosis.

Key lessons from this case include:

- Ensuring the integrity of systems for labeling and handling specimens is critical to ensure that pathology reports are accurate

- Maintaining a chain of custody to track specimens from collection to final disposition and implementing a quality monitoring system (e.g., specimen log) to ensure that all specimens are labeled and transported correctly is essential for patient safety

- Implementing a system that assists in reconciliation of all results—including confirmation of provider receipt, review and transmission of results, and recommendations to the patient—can prevent miscommunication around pathology specimens

Management or treatment issues

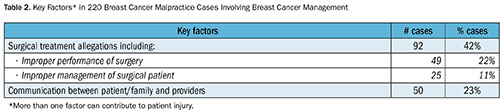

While delay in diagnosis drives a larger percent of cases, there were 220 cases associated with the management or treatment of breast cancer patients following their diagnosis. Surgical allegations account for 42% (92 cases) of these cases (Table 2). Issues with performance of surgery (49 cases, or 22%) were most common, with plastic (29%) and general surgery (16%) the most frequently identified services. These allegations related to both the initial surgery to remove the malignancy and subsequent surgeries to reconstruct the breast. In 14% of these cases, additional surgery was required. Additional surgical allegations were related to preoperative or postoperative management and involve patient dissatisfaction with care and compliance around follow-up care. These cases provide insight into the importance of communication, especially as it relates to the consent process. The remaining nonsurgical cases were related to medication management and minor procedures during the treatment course.

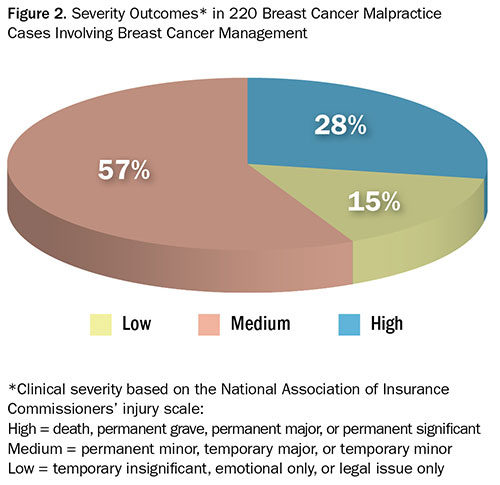

Unlike diagnostic cases, where delay led to high-severity outcomes and death, the outcome of breast cancer cases involving surgical treatment and management are more often medium severity, with issues such as postoperative hematomas, injury to adjacent organs, postoperative infections, and medication errors (Figure 2).

The following cases illustrate management or treatment issues, including system breakdowns:

Case 3

A 49-year-old woman underwent breast reconstruction surgery by a plastic surgeon following bilateral mastectomy due to breast cancer. The patient was in the operating room and under anesthesia when the surgeon realized the type of implants the patient preferred were not listed. The surgeon spoke with the patient’s husband, who said that the p

atient preferred saline implants. Only silicone implants were available, so the surgeon offered to reschedule the surgery. The patient’s husband said to proceed with the surgery and use the silicone implants. The surgery was uncomplicated, with excellent technical results; however, the patient was very upset that silicone had been implanted. She felt she had made it clear to the surgeon on more than one occasion that her preference for the implants was saline. The surgeon offered to replace the implants free of charge, but the patient chose another plastic surgeon to complete the exchange of the implants.

Allegation: The patient alleged emotional distress due to additional surgery.

Key lessons from this case include:

- Understanding and respecting a patient’s preference is key in establishing a healthy provider/patient relationship

- Preparation and communication is an essential part of the preoperative process

Case 4

A 50-year-old woman with aggressive breast cancer underwent a mastectomy performed by a general surgeon followed immediately by reconstructive surgery by a plastic surgeon. According to the operative note, the patient was informed that another procedure for balancing of the breasts would be needed and that perfect symmetry would not be possible due to the pedicle of the TRAM flap. Six months later, the patient had further surgery to excise scar tissue and to revise the breast reconstruction. Over the next year, the patient had two additional procedures, resulting in extensive scarring, an uncentered belly button, and breast asymmetry.

Allegation: The patient sued the general surgeon and plastic surgeon, alleging improper performance of surgery.

- Key lessons from this case include:

- Informed consent discussions are essential to help patients develop a realistic expectation for the results of surgery.

- Documenting the informed consent discussion and including a copy of the information provided to the patient will provide a reference for patients and reduce their need to rely on their memory.

- When results are less than desired, surgeons need to communicate with patients to help them understand future treatment and to link the outcome to the informed consent discussion. Patients may not be happy with the results of surgery, but they will better understand that the results are not due to substandard care.

Summary and risk reduction resources

This analysis demonstrates two key opportunities for improvements in care of patients with breast cancer—one related to timely diagnosis and the other to the ongoing management of care.

Diagnostic error is the leading cause of medical malpractice claims in the U.S. and is estimated to cause 40,000 to 80,000 deaths annually (Leape, 2002). According to the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine (www.improvediagnosis.org), one in every 10 diagnoses is wrong, and one in every 1,000 ambulatory diagnostic encounters results in harm (Graber, 2013). More specifically, a report published by Best Doctors, Inc., notes that cancer misdiagnoses occur as much as 28% of the time, and up to 44% for some types of cancer. A nationwide survey of 400 cancer specialists found that the most misdiagnosed cancer conditions include lymphoma, breast cancer, sarcoma, and melanoma (Exploring diagnostic accuracy in cancer, n.d.). The reasons for misdiagnosis include fragmented or missing information, inadequate time for patient evaluation, and incomplete medical history (Saber-Tehrani, 2013).

Obtaining a timely and accurate diagnosis, including a complete history and physical and interpretation of diagnostic studies, is critical to ensuring the best possible outcome for patients. When there are missing pieces of the diagnostic puzzle, even the most experienced providers can go in the wrong direction. Without an updated family history, a comprehensive exam, and a thorough review of the medical record, a physician with the right intentions can make a wrong decision (Hoffman, 2014).

Equally important to outcomes is the ongoing management of patients once an accurate diagnosis is made. Key vulnerabilities are found in the surgical processes related to treatment, most notably management of surgical complications and the need to address patient expectations. Informed consent is critical to helping patients understand what they can expect from their surgical procedures and reconstructive processes. Supporting an interactive informed consent process, including documentation forms, will assist clinicians in obtaining more comprehensive consent and better aligning their patients’ expectations.

Specific tools have been developed to assist in the diagnosis and management of patient care. Decision support tools, such as a breast care management algorithm and an effective referral tracking system, can assist providers in the diagnostic process. There are also several products available to support providers in developing a comprehensive consent process through the use of interactive guides. Two specific resources that can assist providers in assessing their practice patterns and developing strategies to address potential risks throughout the care process include CRICO’s Safer Care modules (https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Clinician-Resources/Article/2014/Safer-Care-Introduction) and The Doctors Company’s Interactive Guides (http://www.thedoctors.com/KnowledgeCenter/PatientSafety/Interactive-Guides-Site-Surveys-Evaluate-Your-Practice-and-Systems).

Acknowledgment

For their help developing this article, the authors extend their thanks to Robin Diamond, JD, RN, senior vice president of patient safety and risk management at The Doctors Company.

Penny Greenberg is senior program director of patient safety services at CRICO Strategies, a division of The Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions. Previously she was the executive vice president and chief nursing officer at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Needham in Needham, Massachusetts. Greenberg is an experienced educator and has presented widely to audiences on a broad range of patient safety topics with particular emphasis on teaming and culture change. She continues to work as a labor and delivery nurse at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in a per diem position. She received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree from the University of Massachusetts and her master’s degree from Northeastern University. She may be contacted at pgreenberg@rmf.harvard.edu.

Darrell Ranum is vice president of patient safety and risk management for the Northeast Region of The Doctors Company. He is licensed to practice law in Ohio and has more than 25 years of experience in healthcare, professional liability, risk management, and patient safety. As vice president, he supervises risk consulting services and education to hospitals, physician groups, and other organizations insured by The Doctors Company. Ranum also manages studies of medical malpractice claims and suits for the company to identify and communicate system failures that result in patient harm. Ranum serves as vice president for legislation on the board of the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities, is a member of the data sharing committee of the PIAA, and was a founding board member of an inner city charity health center. He is a Certified Professional in Healthcare Risk Management.

Dana Siegal is the director of patient safety for CRICO Strategies, a division of The Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions. She provides analytical and educational services to leading academic medical centers, community hospitals, and physician practices on the issues of medical liability and patient safety. She evaluates the risk profiles of healthcare organizations throughout the country, assesses where current vulnerabilities exist, and makes recommendations for prioritizing action plans. Additionally, she provides oversight to the coding and taxonomy management of CRICO Strategies’ CBS and leads detailed analysis of medical malpractice claims, with a specific focus on diagnostic, OB, electronic health records, and emergency medicine. Siegal is a Certified Professional in Healthcare Risk Management and serves on the board of directors for the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine and the ASHRM annual (faculty) planning committee.

References:

Exploring diagnostic accuracy in cancer: A nationwide survey of 400 leading cancer specialists. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.bestdoctors.com/~/media/PR%20and%20Public%20Affairs/MisdiagnosisSurvey_FINALiv.pdf.

Graber, M. L. (2013). The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(suppl 2), 21-27. Retrieved from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/early/2013/08/07/bmjqs-2012-001615.full.

Hoffman, J. (2014, December 18). Malpractice risks in the diagnostic process. CRICO Strategies. Retrieved from https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/Clinician-Resources/Article/2014/SPS-Malpractice-Risks-in-the-Diagnostic-Process.

Leape, L. L. (2002). Counting deaths due to medical errors. JAMA, 288, 2404-2405.

Saber-Tehrani, A. S., Lee, H., Mathews, S. C., Shore, A., Makary, M. A., Pronovost, P. J., & Newman-Toker, D. E. (2013). 25-year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010; an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22, 672-680. Retrieved from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/22/8/672.

A snapshot of breast cancer. (2014, November 5). National Cancer Institute. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/snapshots/breast.