Personal Candor and the Practice of Medicine

Following a national inquiry into tragic incidents in a regional hospital, disclosure, transparency, and apology are now legally required of healthcare institutions in England.

By Daniel L. Cohen, MD, FRCPCH, FAAP

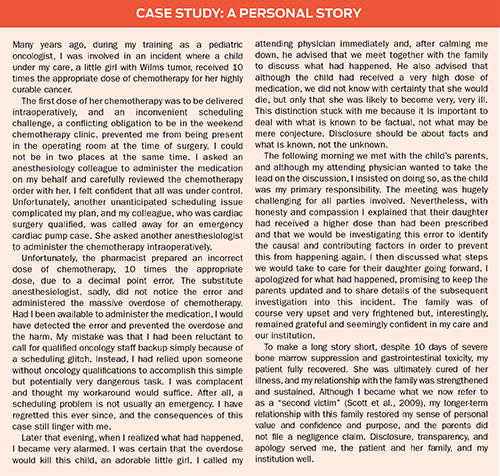

Caring for patients is fraught with hazards and risks. As physicians, every time we approach the bedside we bring the potential for benefit and the possibility of harm. Benevolent intentions do not guarantee safe and effective care or highest-quality outcomes. Problems with our systems and processes of care, as well as personal lapses, often result in preventable and even death.

The processes of diagnosis are complex and encumbered by numerous human factors and cognitive biases. Even if everything is aligned for success, achieving highest quality and safest outcomes can be challenging. Therapeutic interventions and plans can be complex, and furthermore, patients must also be fully engaged for success. Achieving best outcomes is all about trust and mutual obligations, and we must never lose sight of how to achieve these goals.

Though our intentions may be benevolent, we now appreciate that every year, millions of patients are harmed and many, many thousands die as a result of receiving healthcare services. When patients are harmed, they are entitled to apologies and explanations of what has gone wrong as best we understand the circumstances at the time. Initiating these conversations is part of our ethical obligation to nurture trust, which arises from the foundational principles of medical ethics. The primary goal of such conversations is to sustain the doctor-patient therapeutic relationship until when, and if, our patients dismiss us. This is their choice and must be respected.

Moral underpinning of candor and the practice of medicine

It is an imperative that physicians and patients must be partners in maintaining health and achieving best healthcare outcomes. Highest quality and safest outcomes only can be achieved through cooperative engagement, mutual trust, and obligation within this relationship. Professionals are obligated to their patients through the long-established principles of medical ethics, especially the three foundational principles of respect for patient autonomy and decision-making and the intended actions of beneficence and nonmaleficence (Beauchamp & Childress, 2012). We must engage our patients in respectful decision-making and incorporate their goals and beliefs into our therapeutic planning. We must always act in a beneficial fashion, carefully explaining risks and benefits and avoiding biases that may blind our thinking, and we must avoid harming patients or putting them at unnecessary risk of harm. Patients are similarly obliged to share important confidential information with us and to try hard to improve their health and implement healthcare plans. Achieving the highest quality and safest outcomes depends on sharing responsibilities and mutual commitments.

The lack of candor and political consequences

Last autumn, the government of the United Kingdom enacted the “Duty of Candour” legislation (Health and Social Care Act 2008), a statutory obligation applicable to the National Health Service of England (NHS England). This law mandates expeditious disclosure, transparency, and apology when patients have experienced death, severe harm, moderate harm, or prolonged psychological harm. The basis for this legal requirement to mandate candid discussions was the result of the Mid Staffordshire Public Inquiry (Report of the Mid Staffordshire, 2013) into a series of tragic incidents occurring in an NHS England regional health system hospital. This legislation is framed as a criminal law statute, not simply a regulatory requirement, and includes harsh penalties for lack of compliance both for individuals and institutions found in violation of the law. At present, the law focuses on the obligations of institutions, not clinicians per se, but many believe that may be the next step.

The statutory “Duty of Candour,” thus, has taken the failure to do what ordinarily should have been a normal extension of appropriate ethical behavior, originating from our inherent moral obligations to patients, into the realm of criminal behavior. The fact that this was viewed as necessary and appropriate, at least by those in political circles, may be viewed as a failure of healthcare professionals, or the executives and administrators under whom they work, to recognize and adhere to their moral obligations through appropriate ethical behavior. What we have always been ethically obliged to do as part of our humanity and our commitment to patients is now, at least in England, mandated and encompassed in law. In my view, this would never have been necessary had a culture of candor existed in the hospital under investigation and more broadly across NHS England.

When something goes wrong, it is important to remember that sustaining trust is a key element in discussions

that should occur shortly after an incident has been identified. We are still responsible for the care and welfare of our patients, and most assuredly this applies to those we may have harmed. We have a duty to be honest and open with our patients. Admittedly, when patients have died as a result of harm related to healthcare, the goal of disclosure is not sustained engagement in a clinical sense. However, the goal is most certainly sustained engagement in the sense of assisting family members and other loved ones to deal with their grief and anger, even if that is directed toward us or toward our institutions. Thus, disclosure and apology can, and should, be considered the beginning of the healing process, both for patients when they have been harmed and for family members and other loved ones when patients have died.

Sadly, the obligation to be candid, to have these vitally important conversations, including disclosure and apology, has not always been succinctly and compassionately exercised by healthcare professionals in the United States either. This has been either because of their own reluctance or unwillingness to discuss incidents resulting in harm, or because of institutional policies or restrictions, often influenced by the opinions of medico-legal resources.

Some healthcare professionals have expressed a reluctance to apologize or discuss incidents resulting in harm with patients and family members when they personally have done nothing wrong. But these individuals, sadly and most assuredly, are missing the point. The apology is not an admission of personal responsibility, but rather an expression of sadness and regret that someone under their care has been harmed, whatever the reason. It is an expression of sorrow to patients and family members for their inconvenience and suffering. We should want them palpably to feel our sympathy and regret. Not to apologize for harm and suffering is to abrogate a quintessential covenant of our moral responsibility.

In some settings, the purported risk of malpractice claims and lawsuits has resulted in reluctance to share information related to harmful incidents. However, there is now ample and growing evidence that early disclosure, transparency, and apology actually decrease the likelihood of malpractice claims, decrease the levels of compensation, and decrease the frequency of medico-legal lawsuits (Kachalia et al., 2010).

Preparing to meet professional and institutional obligations

Disclosure, apology, and transparency are not new concepts, though they have received increased attention recently as the alarming magnitude of the patient safety harm and death pandemic has become apparent. From an ethical perspective, the duty of candor—the obligations of disclosure, apology, and transparency—has always been part of who we are as professionals. It is part of the moral compass that guides our actions and determines our ethics, i.e., how we should behave when something has gone wrong.

Unfortunately, many physicians and nurses are not specifically trained in delivering bad news, let alone bad news resulting from system or human errors or other mistakes, and especially incidents resulting in death. This training should begin with candid discussions among clinicians regarding their real fears, professional and otherwise, as they are the key stakeholders on the front lines. Addressing their concerns during training is paramount.

Clinicians may need mentoring on how to talk with patients about adverse events. Simulation training should be the norm, and institutions should have in place formal plans that address disclosure as part of an overall incident response plan. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has published guidance on the management of serious adverse events and preparation for disclosure, which should be read and incorporated into local planning (Conway, Federico, Stewart, & Campbell, 2011).

The failure to disclose, apologize, and be transparent represents a failure of healthcare professionals to adhere to the foundational principles of medical ethics and, just as important, represents a failure of hospital leadership to establish and sustain “cultures of candor.” The results of candor and transparency are the potentials for increased trust and sustained engagement, serving the purpose of achieving highest quality and safest outcomes. We must never lose sight of how to achieve these goals. Disclosure, apology, and transparency are foundations of what our professional culture must be and about who we m

ust be as professionals!

Daniel Cohen is chief medical officer for Datix, Ltd, a patient safety software company headquartered in London, England, with subsidiary offices in Chicago and Washington, D.C. He was formerly chief medical officer for the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) TRICARE health plan, covering over 9.5 million beneficiaries worldwide, where he provided oversight for the DoD’s patient safety, clinical quality, and population health programs. Cohen was initially trained in pediatrics and hematology/oncology at the Boston Medical Center, Boston University, and the Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School. He is a senior fellow of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and a fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Cohen is a frequent presenter at international quality and safety conferences and is author of the recently published Late Night Reflections on Patient Safety: Commentaries From the Front Line.

References:

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2012). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Conway, J., Federico, F., Stewart, K., & Campbell, M. J. (2011). Respectful management of serious clinical adverse events (2nd ed.). IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/pages/ihiwhitepapers/respectfulmanagementseriousclinicalaeswhitepaper.aspx.

Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014, Part 3: Section 1. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/327562/Annex_A.pdf.

Kachalia, A., Kaufman, S. R., Boothman, R., Anderson, S., Welch, K., Saint, S., … Rogers, M. A. M. (2010). Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Annals of Internal Medicine, 153(4), 213–221.

The report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry (2013, February). Retrieved from http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., Cox, K. R., McCoig, M. M., Brandt, J., & Hall, L. W. (2009). The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider second victim after adverse patient events. Journal of