Clinician Support: Five Years of Lessons Learned

Clinician Support: Five Years of Lessons Learned

By Laura E. Hirschinger, RN, MSN; Susan D. Scott, RN, PhD; and Kristin Hahn-Cover, MD

PHOTO CREDIT: www.123RF.com

The “second victim” phenomenon is a serious consequence of any healthcare role. As many as half of all healthcare providers will experience the impact of the second victim phenomenon at least once during their careers (Seys et al., 2013). Members of the healthcare workforce have typically suffered in silence from anxiety, stress, shame, and guilt as a result of adverse clinical events (Devencenzi & O’Keefe, 2006; Wolf, 2005; Aasland & Forde, 2005). If not addressed promptly and appropriately, emotional needs may negatively influence the clinician’s career trajectory (Wears & Wu, 2002).

Providing emotional support for healthcare clinicians who may be suffering as second victims is critical for psychosocial and physical recovery after an event (Dekker, 2013). Despite knowledge that unexpected clinical events, particularly those relating to medical errors, can have ominous emotional consequences, most workplaces do not provide adequate emotional support for their personnel (Conway et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011). Without appropriate emotional support during this critical period, providers may experience prolonged personal suffering and long term consequences such as premature departure from their chosen profession (Scott, 2013).

University of Missouri Health Care (MUHC), an academic healthcare system located in Columbia, Missouri, deployed an evidence-based emotional support structure for second victims based on research with recovering second victims (Scott et al., 2011). MUHC is a six-hospital healthcare system with 52 ambulatory clinics and approximately 6,500 employees. The second victim support structure, known as the forYOU Team, was designed to increase awareness of the second victim phenomenon, “normalize” the psychological and physical impacts, provide real-time surveillance for possible second victims within clinical settings, and render immediate peer-to-peer emotional support when a potential second victim is identified (Paparella, 2011).

Intervention—The Second Victim “Caring Moment”

The MUHC second victim interventional model uses The Theory of Transpersonal Caring and the Critical Incident Stress Management Model as theoretical frameworks to optimize interventional strategies for mitigating suffering. Jean Watson’s Theory of Transpersonal Caring provided a practice model focused on human caring within the context of a compassionate relationship (Watson, 2008). Critical Incident Stress Management provided a response model founded through providing immediate psychological support after a traumatic event, typically in a community-based setting (Everly et al., 2002).

Our Second Victim Transpersonal Care Model provides a structure for alleviating individual clinician harm using a second victim “caring moment.” This intervention offers comfort measures, alleviation of pain and suffering, and promotion of healing using this model of escalating support. It begins with surveillance during high-risk clinical events by leadership and colleagues knowledgeable about the second victim phenomenon.

forYOU Interventions

The MUHC forYOU Team was specifically designed to provide confidential peer-to-peer support for clinicians reacting to a stressful clinical event and addresses the clinician’s unique needs using a three-tiered model of comprehensive support (Scott et al., 2010).

The goal of forYOU Team intervention is to help clinicians return to pre-event performance after an unanticipated/adverse event and, ultimately, to thrive in their careers. The three-tiered interventional model (Figure 1) defines a comprehensive network of support (Scott et al., 2010). Tier 1 provides immediate “emotional first aid” from colleagues and/or supervisors in the clinician’s department or unit. Unit leaders are expected to monitor staff after a potentially distressing clinical event. They have been educated on the second victim phenomenon and immediate supportive interventions to consider.

The goal of forYOU Team intervention is to help clinicians return to pre-event performance after an unanticipated/adverse event and, ultimately, to thrive in their careers. The three-tiered interventional model (Figure 1) defines a comprehensive network of support (Scott et al., 2010). Tier 1 provides immediate “emotional first aid” from colleagues and/or supervisors in the clinician’s department or unit. Unit leaders are expected to monitor staff after a potentially distressing clinical event. They have been educated on the second victim phenomenon and immediate supportive interventions to consider.

In Tier 2, trained peers monitor colleagues for second victim responses and provide immediate support in the form of a second victim caring moment. The forYOU Team provides two forms of structured interventions: 1) one-on-one second victim caring moments and 2) group debriefings when a team experiences an unanticipated clinical event together. Both interventions use basic elements of support incorporating a caring moment. They are based on the knowledge that individual clinicians may require differing intensity and duration of support during emotional recovery. One-on-one interventions are held as soon as a second victim is identified. Debriefings are scheduled to ensure the majority of personnel involved in the event are able to participate. Debriefings are facilitated by senior forYOU Team leaders with additional group crisis training.

Tier 3 ensures availability and prompt access to professional counseling and guidance services for clinicians requiring support beyond the capabilities of the trained peer (Scott et al., 2010).

The forYOU steering team realized that deployment of a second victim support infrastructure would take significant effort and commitment to ensure coverage across the MUHC. The team was launched with careful selection of the initial 51 peer supporters as front-line volunteers. Initial team member selection focused on high-risk clinical areas and teams. In the years to follow, team leaders recruited personnel from clinical areas not previously represented. In four training sessions to date, we have prepared 137 peer supporters with representatives from each MUHC hospital.

|

|

Methodology

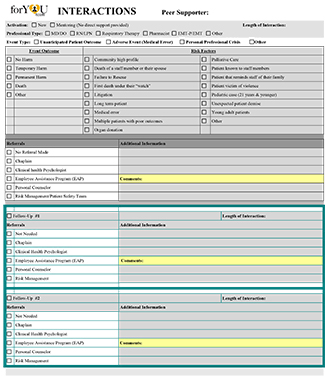

To monitor forYOU Team activations, a data collection tool was developed in collaboration with General Counsel to capture the type of support intervention, clinician type, and basic details of the intervention (Figure 2). Data collection allows monitoring of overall team performance. Use of this tool provided basic information about peer support and additional insights stimulating innovation in future design.

After activations and during monthly team meeting review of recent activations, forYOU interventionalists complete data collection forms. Measures of team performance are shared in team meetings and executive summaries.

Five-Year Review

During the first five years of the MUHC forYOU Team, members documented emotional support in the form of mentoring, group debriefings, and one-on-one support for 1,075 clinicians. An overview of activations is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Activation Overview |

||||

| Participants | ||||

| Mentoring | Group Debriefing | One-On-One | Totals | |

| Year One | 3 | 82 | 50 | 135 |

| Year Two | 12 | 165 | 76 | 253 |

| Year Three | 11 | 163 | 77 | 251 |

| Year Four | 13 | 144 | 102 | 259 |

| Year Five | 8 | 78 | 91 | 177 |

| Totals | 47 | 632 | 396 | 1075 |

Tier 1- Department Support and Leadership Mentoring

Clinician support occurs most commonly at the local level, offered by unit leadership and colleagues who provide a caring presence within the work environment of the clinician. Unit leaders are encouraged to understand area-specific clinical scenarios that are high risk for eliciting a second victim response. When an event occurs, leaders monitor personnel for potential second victim responses and intervene accordingly. Depending on unit culture and activity, Tier 1 interventions can be frequent or infrequent. These local interventions are “pre-activation”; activation data are not captured.

Most managers/supervisors are comfortable providing basic Tier 1 support; they may, however, access forYOU Team leaders for additional insights and guidance. On 47 occasions this “just in time” mentoring was offered. The guidance equipped leaders with knowledge and skills to provide appropriate and necessary support. Mentoring interactions averaged 20 minutes in duration. Most mentoring (62%, n=29) was offered to nursing leaders, but mentoring was also provided to medical staff and other allied health professional leaders. Reasons for mentoring interactions were varied but could be categorized into three distinct groups: unanticipated patient outcome, personal or professional crisis, and adverse event (associated with medical error). Most mentoring events (55%, n=26) were related to a personal or professional crisis experienced by an individual healthcare team member with potential to impact the entire care team. Examples include unexpected deaths/suicide of co-workers, workplace violence with clinician injury, and natural disasters impacting the geographic region of the hospital. Twenty-eight percent (n=13) of the mentoring interactions were related to unforeseen/unanticipated patient outcomes not related to a medical error. Examples include unexpected patient decline, motor vehicle crash with multiple fatalities, organ donation, and fetal death. Seventeen percent (n=8) were associated with an adverse event related to a medical error.

Tier 2 – Peer Support Experts

The interventions within Tier 2 include group debriefings and one-on-one caring moments. A total of 1,028 individuals received support within this tier.

Table 2. Risk Factors Evoking Second Victim Response: Group Debriefings |

|

| Risk Factor* | Group Debriefing |

| Pediatric case (< 21 years) | 46 |

| First death under “their watch” | 21 |

| Unexpected patient demise | 21 |

| Long term patient | 16 |

| Multiple patients with bad outcomes | 12 |

| Patient known to staff member | 11 |

| Patient that reminds staff of their family | 9 |

| Young adult patient | 9 |

| Organ donation | 8 |

| Community high profile patient | 6 |

| *More than one risk factor may exist per activation. | |

Group debriefings

Group debriefings provided support for the majority of clinicians engaged through Tier 2 intervention, with 632 (61.5%) clinicians and 83 sessions. Average group size was eight, and sessions lasted an hour. Most group debriefings were convened after unforeseen/unanticipated patient outcomes (65%, n=54). Thirty-three percent (n=27) related to a personal/professional crisis experienced by an individual healthcare team member. Two percent (n=2) followed an adverse event related to a medical error with multiple clinicians involved.

Group debriefing risk factor analysis revealed caring for a complicated pediatric case was the most common trigger, particularly when the patient died. Other risk factors included first death experiences, unexpected patient demise, long-term patient death, and multiple patients with poor outcomes within a short period of time. Table 2 summarizes the top 10 risk factors identified in forYOU Team group debriefings. In fifteen group debriefings (18%), none of the previously identified risk factors were applicable, and risk factors were not identified in four (4.8%) debriefings.

One-on-one caring moments

One-on-one interventional support accounts for 38.5% (n=396) of Tier 2 interventions. Average encounter duration is 24 minutes. Approximately one-third require follow-up contact to ensure clinician’s emotional needs are met. Fifty-three percent (n=211) of clinicians supported were registered nurses or licensed practical nurses. Physicians (attending physicians, fellows, and resident physicians) represented 23% (n=91). Seventeen percent (n=69) represented unlicensed staff members, including students, volunteers, clerks, dietary, plant engineering, and environmental services. Other licensed clinicians supported (n=25) included pharmacists, social workers, therapists, and paramedics.

Table 3. Risk Factors Evoking Second Victim Response: One-on-On |

|

| Risk Factor* | One-On-One |

| Pediatric case (< 21 years) | 46 |

| First death under “their watch” | 21 |

| Unexpected patient demise | 21 |

| Long term patient | 16 |

| Multiple patients with bad outcomes | 12 |

| Patient known to staff member | 11 |

| Patient that reminds staff of their family | 9 |

| Young adult patient | 9 |

| Organ donation | 8 |

| Community high profile patient | 6 |

| *More than one risk factor may exist per activation. | |

Reasons for one-on-one activations of forYOU Team services were categorized. Most activations (55%, n=218) were related to unforeseen/unanticipated patient outcomes. Twenty-eight percent (n=111) related to a personal/professional crisis. Seventeen percent (n=67) were associated with an adverse event related to a medical error. A one-on-one caring moment is our preferred method of support after a medical error, due to the sensitive nature of such an event.

One-on-one support risk factor analysis demonstrated risks similar to those identified in group debriefings. In 31% (n=124) of activations, none of the previously identified risk factors were relevant. Approximately 15% (n=59) of one-on-one activations had no risk factor identified. An overview of the top ten risk factors requiring one-on-one support is provided in Table 3.

Tier 3 – Professional Resources

Table 4. Professional Counseling/Guidance Referrals by Intervention Type |

|||

| Referral Support | Mentoring | Group Debriefing | One-On-One |

| No Referral Required | 44 | 587 | 340 |

| Employee Assistance Program (EAP) | 1 | 5 | 27 |

| Personal Counselor | 0 | 2 | 17 |

| Risk Management/Patient Safety Team | 0 | 13 | 15 |

| Chaplain | 2 | 16 | 8 |

| Clinical Health Psychologist | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| One-On-One* | N/A | 16 | N/A |

| *Referral to one-on-one support offered post-group debriefing | |||

Tier 1 and Tier 2 addressed the majority of clinician needs (90.3%, n=971), while 9.7% (n=104) individuals required professional referrals. Table 4 provides an overview of professional counseling/guidance referrals by the three primary support interventions. Referral to Tier 3 resources varied in frequency based on forYOU Team activation type. Fourteen percent (n=56) of one-on-one activations required referral while only 7% (n=45) of group debriefing participants and 4% (n=3) of mentoring interactions led to Tier 3 support.

Lessons Learned

During the past five years of service, the forYOU Team has changed MUHC’s system-wide response to unanticipated clinical events and provided a new infrastructure for post-event clinician support. Through deployment of this program, we have identified challenges to and insights about providing clinician support within the context of a busy clinical environment.

Organizational Implications

A strong patient safety culture is an essential foundation for implementation of a clinician support program. With a clearly defined system approach to patient safety investigations, we create a safe environment in which we may address the emotional well being of those involved. Staff psychological safety is expected. This “safe environment” in turn further elevates the patient safety culture with increased reporting and interdisciplinary teamwork.

Partnership between unit and forYOU Team leaders has benefitted the working dynamics between front-line staff and supervisors in the aftermath of critical events. Departmental leaders, educated about the second victim phenomenon, provide a supportive presence for staff and demonstrate a true commitment to care of the caregiver during stressful times.

Engaged executive champions have been pivotal to the success of this program. Since its inception, the forYOU Team has benefited from support and direct participation by MUHC and School of Medicine leaders. These executive champions understand that peer support is essential to promoting the well-being of clinicians in the aftermath of an unanticipated clinical event.

Awareness of the second victim phenomenon helps normalize the pain and suffering and contributes to recovery. We strongly recommend the first initiative in a healthcare facility be an educational campaign to broadly introduce the second victim concept.

Team Function/Design

Determining the appropriate department to provide administrative team oversight is an important initial consideration. At MUHC, patient safety and risk management leaders working under the direction of the chief quality officer provided the cornerstone for team design and coordination. This partnership has facilitated a more transparent and predictable post-event response strategy.

Defining objectives is essential for designing support interventions. Prior to deployment at MUHC, the forYOU steering team identified six objectives for monitoring team performance:

- Minimize human toll/suffering after unanticipated adverse clinical events.

- Provide a “safe zone” for healthcare personnel to receive support.

- Deploy an internal rapid response team of “emotional first aid” for providers.

- Monitor team activations/deployments maximizing program effectiveness.

- Increase awareness of second victim phenomenon.

- Provide leadership/management resources to support providers.

Over time, the forYOU Team has become a “go to” resource for responding to critical situations within MUHC. An unintended consequence has been activation of the team for services beyond the scope of the team’s design and training. Examples include employee performance concerns, employee-employer conflict, and stress from organizational restructuring. Team leaders made a conscious decision to limit the scope of forYOU Team interventions to adverse events related to medical error, unforeseen/unanticipated patient outcomes, and personal/professional crisis impacting the healthcare team.

Identifying professional resources for Tier 3 intervention is necessary to ensure the unique needs of each clinician are met. The forYOU Team recruited mental health professionals within MUHC and the University of Missouri to provide expedited care for clinicians who need a level of care higher than peer support. Establishing working relationships with these professionals either internal or external to a healthcare organization ensures the ability to provide appropriate support. For the MUHC forYOU Team, these individuals have also been pivotal in team member educational efforts and ongoing mentoring.

Peer Supporter Characteristics

The forYOU Team is comprised of individuals representing numerous clinical areas with 24/7 coverage. Prospective members are identified by team leaders and nominated by managers based on interpersonal skills and professional attributes. Maintaining strict confidentiality is essential.

ForYOU Team training focuses on identifying second victims, providing individual crisis support, and using critical communication techniques and stress management interventions. Simulations of one-on-one interactions allow practice of new skills in a nonthreatening and safe environment. Knowledge and skills are reinforced in regular team meetings. A four-part meeting agenda consists of

- operational issues,

- spreading awareness of second victimization and forYOU Team resources,

- discussing de-identified cases, and

- providing education.

Second Victim Insights

In high-acuity areas of healthcare, there is minimal protected time for clinicians to comprehend and process an unanticipated or adverse event before moving to the next duty. The strategic placement of trained peers in these areas allows for real-time emotional support.

Despite published literature about the second victim phenomenon and local efforts to disseminate information about the phenomenon and available support, there remains a perception of “weakness” related to seeking support. It is difficult for clinicians to acknowledge they are distressed by a clinical event and need assistance (DeWit, Marks, Natterman, & Wu, 2013). At MUHC, we have found that clinicians often will not actively seek support but instead will suffer in silence or wait to be approached. Trained peers, equipped with knowledge and skills for recognizing behavioral changes suggestive of a second victim response, are able to bring an intervention to the clinician’s “normal” activities and address support needs.

An additional insight from our five years of support is clinicians’ intense “fear of the unknown” related to the unanticipated/adverse events. The nature of this fear changes based on the clinician’s profession. Medical staff members worry most about litigation while other professionals are fearful about losing their professional licensure and ultimately their jobs. Understanding these fears and proactively addressing them during post-event caring moments, with Tier 3 referrals when needed, allows peer supporters to decrease clinician suffering.

When identifying potential individuals impacted by an adverse clinical event, institutions must look broadly. Students, clerical staff members, and other non-clinical personnel may be overlooked when support is offered to entire teams. These individuals play important roles in the successful functioning of healthcare teams and should be considered when supportive interventions are designed and planned.

Conclusion

The forYOU Team’s five-year experience in providing clinician support has yielded many valuable insights into this aspect of MUHC’s patient safety culture. Organizational awareness of the second victim phenomenon and an institutional response plan are critical steps in minimizing the suffering of the institution’s healthcare clinicians. From this experience, the authors strongly encourage healthcare facilities to develop a comprehensive plan and provide accessible, effective support for all clinicians experiencing the second victim phenomenon. Interventional support should begin the moment the unanticipated/adverse event is recognized. Peer and social support initiatives should be established, with information about them disseminated widely so clinicians know what support is available, what can be expected, and how to access help when they experience such an event. Clinician support must become a predictable, required part of the healthcare operational response to stressful clinical events.

All of the authors work at University of Missouri Health System in Columbia, Missouri.

Laura Hirschinger is the performance improvement professional. Her graduate degree focused on the practice of holistic nursing. She serves as team leader of MUHC’s forYOU Team. Hirschinger may be contacted at Hirschingerl@health.missouri.edu.

Susan Scott is manager of patient safety/risk management. Her research includes understanding the second victim phenomenon in an attempt to develop effective institutional supportive interventions. She is coordinator of MUHC’s forYOU team. Scott may be contacted at scottd@health.missouri.edu.

Kristin Hahn-Cover is the chief quality officer. She provides administrative oversight of MUHC’s forYOU Team and serves as team leader for the School of Medicine. Her clinical practice is as an internal medicine hospitalist. Hahn-Cover may be contacted at Hahncoverk@health.missouri.edu.

References

Aasland, O. G., & Forde, R. (2005). Impact of feeling responsible for adverse events on doctors’ personal and professional lives: the importance of being open to criticism from colleagues. Quality and Safety in HealthCare, 14(1), 13-17.

Conway, J., Federico, F., Stewart, K., & Campbell, M. (2011, March). (2nd ed.) Respectful management of serious clinical adverse events (White Paper – IHI Innovation Series). Retrieved from Institute for Healthcare Improvement: www.ihi.org/IHI/WhitePapers/.

DeWit, M. E., Marks, C. M., Natterman, J. P., & Wu, A. W. (2013). Supporting second victims of patient safety events: shouldn’t these communications be covered by legal privilege? Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics, 852-858.

Dekker, S. (2013). Second victim – error, guilt, trauma and resilience. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Devencenzi, T., & O’Keefe, J. (2006). To err is human: supporting the patient care provider in the aftermath of an unanticipated clinical event. Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 8, 131-135.

Everly, G. S., Flannery, R. B., & Eyler, V. A. (2002). Critical incident stress management (CISM): a statistical review of the literature. Psychiatric Quarterly, 73(3), 171- 182.

Hu, Y. Y., Fix, M. L., Hevelone, N. D., Lipsitz, S. R., Greenberg, C. C., Weissman, J. S., & Shapiro, J. (2011). Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors. Archives Surgery. DOI:10.1001/archsurg.2011.312.

Kohn, L.T., Corrigan, J.M., & Donaldson, M.S. (Eds). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences Press.

Paparella, S. (2011). Caring for the caregiver: moving beyond the finger pointing after an adverse event. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 37(3), 263-265.

Scott, S. D. (2013). The second victim experience: caring for our own. MLA Physician Risk Management, 10(1), 1-6.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., McCoig, M. M., Cox, K. R., Hahn-Cover, K., & Hall, L. W. (2011). The second victim. In M. A. DeVita, K. Hillman, & R. Bellomo (Eds.) (Ed.), Textbook of rapid response systems (p. pp. 321-330). New York, N.Y.: Springer.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., Cox, K. R., McCoig, M., Hahn-Cover, K., Epperly, K. M., … Hall, L. W. (2010). Caring for our own: deploying a system wide second victim rapid response team. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 36(5), 233-240.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., Cox, K. R., McCoig, M. M., Brandt, J., & Hall, L. W. (2009). The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider second victim after adverse patient events. Journal of Quality and Safety in Health Care, 18, 325-330.

Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., & Cox, K. R. (2008). Sharing the load: rescuing the healer after trauma. RN, 71, 38-43.

Seys, D., Wu, A. W., VanGerven, E., Vleugels, A., Euwema, M., Panella, M., … Vanhaecht, K. (2013). Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 36(2), 133- 160. DOI: 10.1177/0163278712458918.

Watson, J. (2008). Nursing – The philosophy and science of caring (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: F.A. Davis Company.

Wears, R. L., & Wu, A. W. (2002). Dealing with failure: the aftermath of errors and adverse events. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 39, 344-346.

Wolf, Z. R. (2005). Stress management in response to practice errors: Critical events in professional practice. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System-Patient Safety Advisory, 2, 1-4.